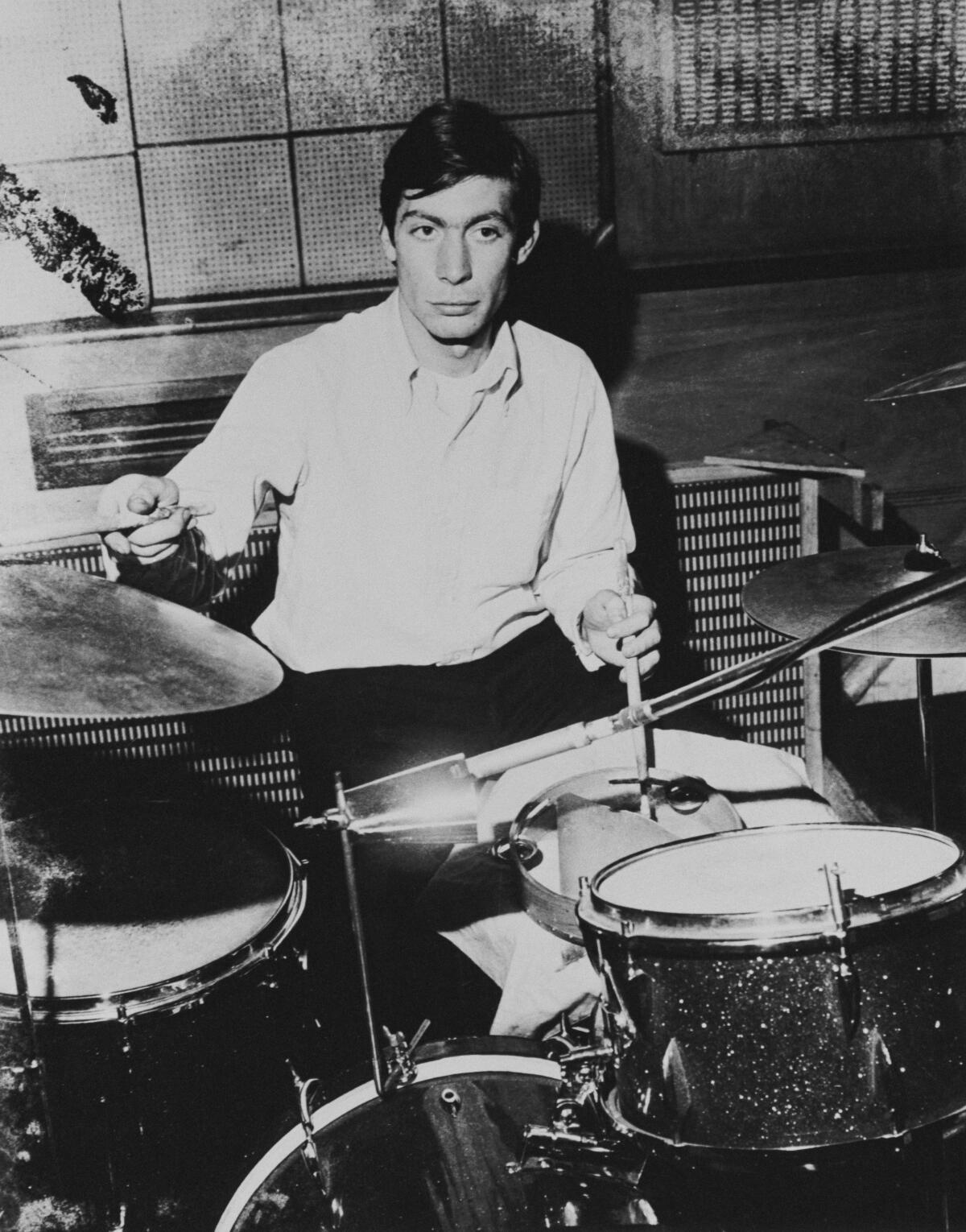

Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts, the band’s ‘secret essence,’ dies at 80

Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watt has died at the age of 80, according to his publicist.

Charlie Watts, the drummer who anchored the Rolling Stones throughout their reign as the World’s Greatest Rock & Roll Band, died on Tuesday. He was 80.

His death was announced by a spokesperson for the group: “It is with immense sadness that we announce the death of our beloved Charlie Watts. He passed away peacefully in a London hospital earlier today surrounded by his family.

“Charlie was a cherished husband, father and grandfather and also as a member of the Rolling Stones one of the greatest drummers of his generation.”

The Rolling Stones drummer, who joined the group in 1963 and never missed a gig, died Tuesday at age 80.

The cause of death was not disclosed. Watts had suffered from health problems in recent years, including a diagnosis of throat cancer in 2004.

Earlier this month, Watts announced that he was unable to participate in the forthcoming leg of the Stones’ No Filter tour due to his health. He had not missed a Rolling Stones concert since joining the band in 1963.

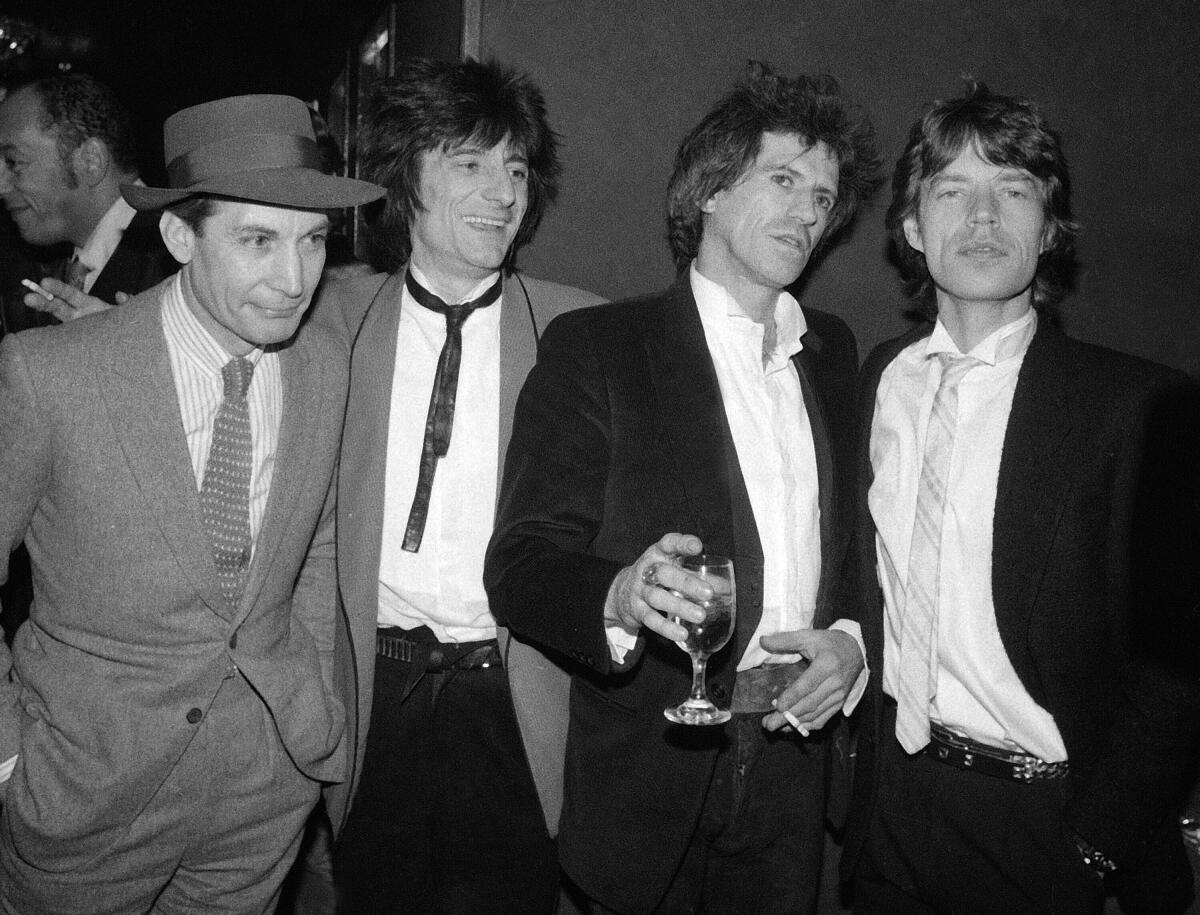

In his 2010 memoir “Life,” Stones guitarist Keith Richards wrote, “To me, Charlie Watts was the secret essence of the whole thing.” Paul McCartney posted a brief tribute video on Twitter, calling Watts “a lovely guy” and “a fantastic drummer.” Elton John said on Twitter that Watts was “the ultimate drummer. The most stylish of men, and such brilliant company.” Questlove, the drummer for the Roots, posted on Instagram that Watts was “the heartbeat of Rock & Roll”

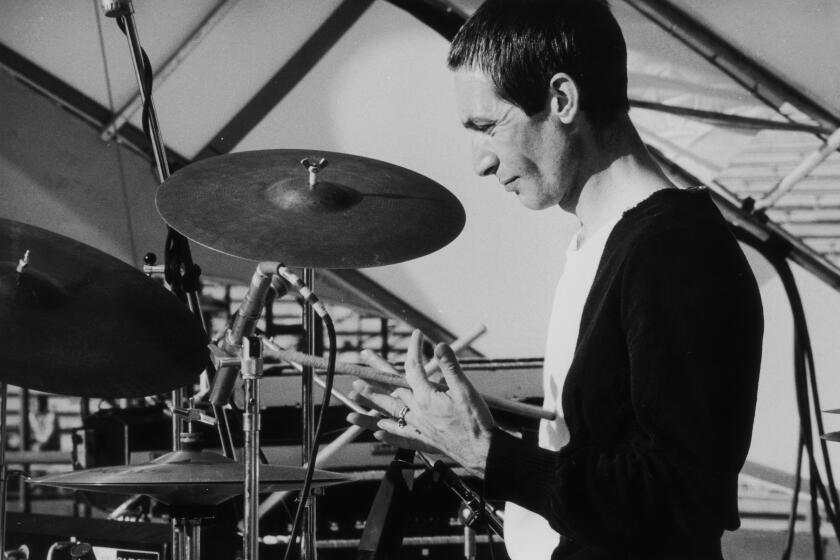

Watts always seemed to stand slightly apart from the rest of the Rolling Stones. He was the quiet, dapper center of gravity around which the bad boys orbited. Watts gave the Stones a sense of swing, emphasizing the roll in rock ’n’ roll, an element missing in many of their imitators. Watts came to that swing naturally, falling in love with jazz long before he learned about the blues, and often returning to it whenever he stepped outside of the Rolling Stones.

While concert promoters pledge to keep fans safe by mandating proof of vaccination to attend shows, artists are still canceling tours in increasing numbers.

The son of a London truck driver, Watts was born in the Bloomsbury neighborhood of London on June 2, 1941. As a child in Wembley, Watts became an enthusiastic fan of jazz, collecting 78 rpm records by the likes of Charlie Parker. While attending Kingsbury’s Tylers Croft Secondary Modern School as a teenager, Watts decided to learn to play drums. He bought a banjo, took off its neck and used the banjo head as a snare drum, teaching himself with a pair of wire brushes. Soon, he upgraded to a full drum kit his father purchased from a friend. Watts didn’t take lessons. He attempted to play along to his records, a task he hated doing, but it helped build his chops. He’d later recall, “I wanted to be Max Roach or Kenny Clarke playing in New York with Charlie Parker in the front line. Not a bad aspiration. It actually meant a lot of bloody playing, a lot of work.”

As Watts racked up the hours playing drums for the Jo Jones All Stars, he also attended Harrow Art School, before leaving for a position as a graphic designer at an advertising firm. Watts continued on this split course — design during the day, jazz at night — through his time playing in Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. After a brief spell working as a designer in Copenhagen, he settled in Blues Incorporated through 1962 as he was being pursued by Richards and guitarist Brian Jones to join the blues band they were forming with Mick Jagger, bassist Bill Wyman and pianist Ian Stewart.

Watts accepted the invitation in January 1963, making his debut on the 12th of that month at the Ealing Blues Club. By that summer, the band hired as their manager Andrew Loog Oldham, who decided to position the Rolling Stones as the “anti-Beatles” — London bad boys to the Liverpudlian mop-tops. Oldham convinced the Stones to push Stewart out of the lineup — the burly pianist didn’t fit their lean image, though he remained in the band’s orbit as a road manager and studio pianist — just before the release of their first single, a cover of Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” which arrived in June, just six months after Watts became a Stone.

The Rolling Stones’ rise was swift. The Beatles gave them “I Wanna Be Your Man” for their second single, they cracked the U.K. Top 40 in February 1964 with a cover of Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away” and in June 1964 had their first British No. 1 with a version of Bobby & Shirley Womack’s “It’s All Over Now.” A year later, they hit the top of the charts on both sides of the Atlantic with “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Richards’ fuzz-toned riff helped turn “Satisfaction” into the group’s signature song but Watts’ steady roll propelled the single, giving it an indelible swing.

Following “Satisfaction,” the hits came swiftly, as did the international tours, with the Stones’ reputation for debauchery rising as the Swinging 1960s came to a head. Watts didn’t participate in much of the revelry, at least during the 1960s and early ‘70s. He married Shirley Shepherd in 1964; the couple would remain together throughout the rest of Watts’ life. He published “Ode to a High Flying Bird,” an illustrated tribute to his idol Charlie Parker, in 1964, and started to participate in the design of Rolling Stones album art; their 1967 album “Between the Buttons” is festooned with his cartoons.

Watts was showcased on the cover of the band’s 1970 live album, “Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!” — he’s the only Stone on the cover, brandishing two guitars and a top hat — and Jagger gave him a shoutout on the record itself, telling the crowd, “Charlie’s good tonight, isn’t he?” Yet he seemed happiest providing the band a steady anchor. He didn’t let ego get in his way: When he heard the backing track for the group’s 1974 record “It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll (But I Like It),” he thought the rhythm Kenney Jones laid down on the demo was good enough for the finished album. Starting with the band’s 1975 tour, Watts collaborated with Jagger on the stage design for the group’s concerts, a role he continued to play throughout his life.

Watts did have a period of substance abuse, one that began in the late ‘70s as he started to use heroin. He still managed to play convincingly on record — the disco-inspired beats of 1978’s “Miss You” and 1980’s “Emotional Rescue” showed that he could adapt to the times — but his drug use became severe enough that Richards, a notorious abuser of heroin, convinced him to give it up. The drummer finally got sober in 1986.

His sobriety coincided with his extracurricular project, the Charlie Watts Orchestra, a jazz group that released its first album, “Live at Fulham Town Hall,” in 1986. Over the next two decades, Watts stepped outside of the Stones to play jazz, often with a smaller group called the Charlie Watts Quintet, which toured and recorded regularly in the early 1990s. In 2000, he collaborated with fellow drummer Jim Keltner on an album aptly called “The Charlie Watts-Jim Keltner Project.”

The Grammys presented the Rolling Stones a lifetime achievement award in 1987, the first Grammy the group took home. They went on to win three subsequent awards, including rock album for “Voodoo Lounge” in 1995 and traditional blues album for “Blue & Lonesome” in 2018. The Stones were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989.

In 2004, the Charlie Watts Tentet released the live album “Watts at Scott’s.” By the time of its August release, Watts was diagnosed with throat cancer. He recovered swiftly, rejoining the Rolling Stones for “A Bigger Bang,” a 2005 album that would be their last album of original material featuring Watts. The album’s supporting tour was captured in Martin Scorsese’s 2008 documentary “Shine a Light.” The Rolling Stones toured steadily through the 2010s, including a headlining appearance at the 2016 Desert Trip festival, which also featured fellow rock ’n’ roll survivors Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan and Neil Young. That year, the Rolling Stones released “Blue & Lonesome,” a collection of blues covers, and the final album Watts would play on.

Originally scheduled for 2020, the North American leg of the Stones’ No Filter tour was postponed until the fall of 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On Aug. 5, Watts announced he would not be participating in the tour due to a medical issue. He approved his replacement, Steve Jordan, who has drummed with Richards since the 1980s.

Watts is survived by his wife, Shirley; daughter, Serafina; and granddaughter, Charlotte.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.