Beyond the Black History Month hit parade

Black History Month reminds me of a really great golden oldies station, always blaring the same handful of terrific tunes. Every February, it plays Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman soul — with a chorus or two of the George Washington Carver blues.

Now don’t get me wrong. This is my kind of history, and my kind of heroes, and I understand why we must tell every generation their stories. I just think that including some fresh tales too would produce a far fuller picture of how blacks enriched America.

Rosa Parks, for example, had many counterparts. One was Irene Morgan. Eleven years before Parks refused to surrender her seat to a white man on an Alabama bus, Morgan did the same thing on a Greyhound bus in Virginia. But Morgan’s response was far from soft-spoken. She first refused to let the young, baby-carrying woman sitting next to her give up her seat. Morgan then ripped up her arrest warrant and threw it out a window. The high-heels-wearing Morgan also kicked a sheriff’s deputy in what she called “a very bad place.” When another deputy tried to touch her, she tore his shirt.

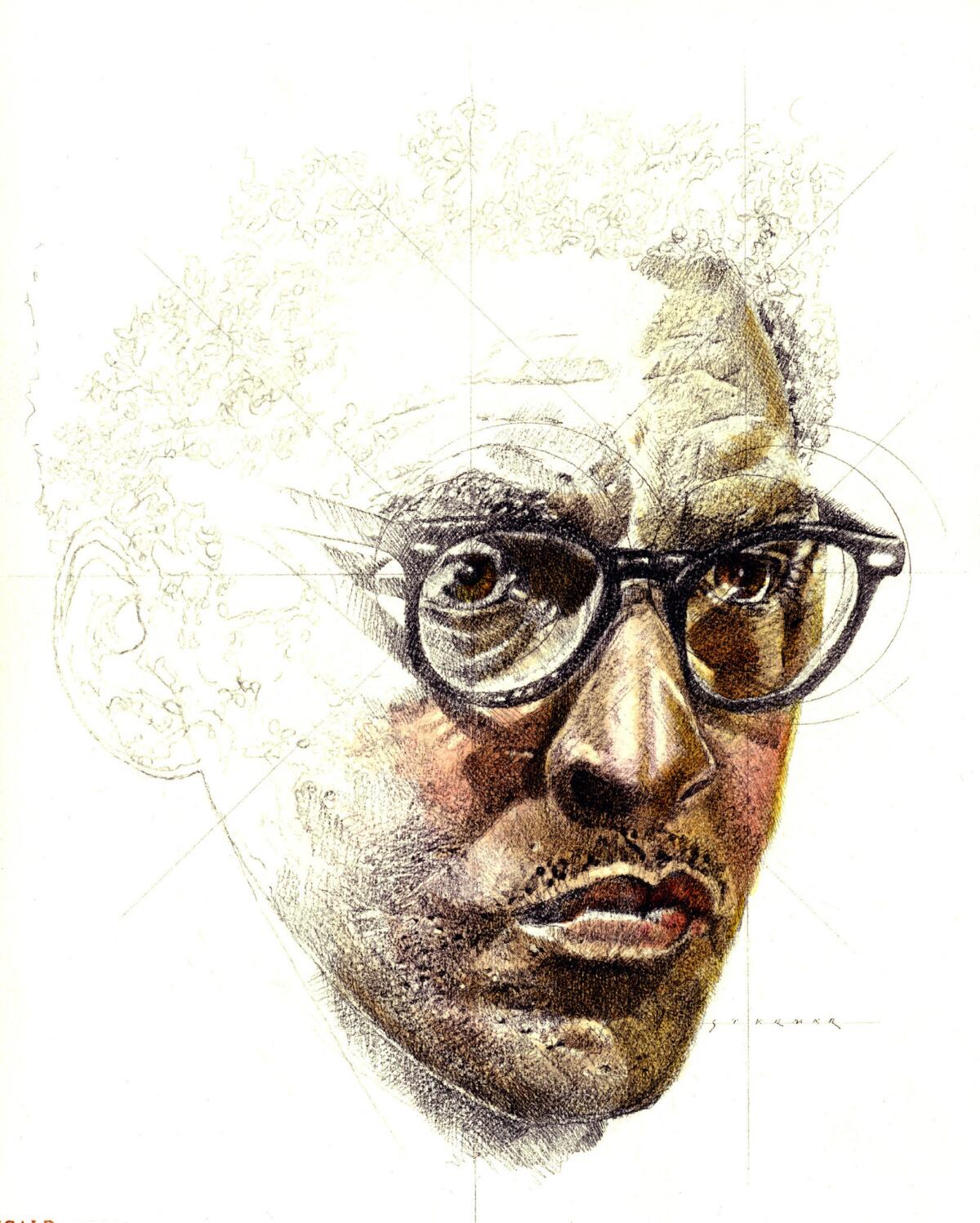

PHOTOS: Let’s celebrate some of America’s unsung heroes this Black History Month

NAACP lawyers appealed Morgan’s 1944 arrest and fine all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. That resulted in a 1946 decision ending segregation on interstate buses.

In the South, though, some Greyhound drivers ignored the ruling. As a result, young white and black activists began testing the decision by riding together on interstate buses. Often arrested and sometimes beaten, they became known as Freedom Riders. One rider was Bayard Rustin, who would later organize the unforgettable 1963 March on Washington.

Martin Luther King Jr. is another Black History Month favorite, justly celebrated for pushing America to fulfill its promise of liberty and justice for all. Yet we seldom hear about Dorothy Cotton, and she was a giant too. She grew up in a shotgun shack on an unpaved road in Goldsboro, N.C., to become part of King’s inner leadership circle.

As head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Citizenship Education Program, Cotton trained the citizens who became the tireless feet and bottomless faith of the modern civil rights movement. She taught them to understand the Constitution, hold meetings, organize marches, practice nonviolence and endure abuse without striking back. Most important, she taught ordinary people to believe that changing themselves would ultimately change their country. Shouldn’t we hear her story?

Harriet Tubman, the never-turn-back conductor on the slave-freeing network known as the Underground Railroad, always gets an annual salute. Why not? I mean, who doesn’t love Harriet Tubman? But people should also hear the story of Kentucky’s Arnold Gragston, who, while still enslaved himself, rowed more than 100 escaping slaves across the Ohio River to freedom.

The scientific contributions of George Washington Carver are celebrated each February, and rightly so. He is credited with discovering several hundred uses for peanuts, soybeans, sweet potatoes and other plants, and for persuading the South to enrich its soil by rotating crops.

But what about Carver’s good friend Claude Harvard, whose automatic piston pin inspection device was one of the stars of the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair? The son of a Georgia sharecropper and a maid, Harvard worked for Ford Motor Co., where he invented a machine that inspected piston pins and rejected faulty ones at the rate of 1,500 an hour. He also created a process enabling workers to roll steel into thinner, stronger sheets, which Ford sold to U.S. Steel Corp. for a quarter of a million dollars. Harvard helped build testing devices for two-way car radios for Detroit’s Police Department as well. Later, he brought together George Washington Carver and Henry Ford.

Black war heroes don’t get a lot of ink in February either. But Cpl. Miles James certainly earned that title. One of more than 200,000 black troops who helped the Union win the Civil War, James had one arm amputated during the Battle of New Market Heights in Virginia on Sept. 29, 1864, but continued loading and firing his weapon with his other hand and arm. He and 13 other black soldiers won Medals of Honor for their furious and brilliant fighting there.

Meanwhile, John Robert Bond, a half-black Englishman, crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a merchant ship to join the U.S. Navy and fight in the Civil War. He is almost as forgotten as Maria Lewis, an African American woman who passed as a white male soldier to serve in the 8th New York Cavalry.

Another of my nominees for attention this month is a mixed-race woman named Edmonia Lewis, who battled prejudice against women, African Americans and Native Americans to become a skilled sculptor in the 19th century. Some prospective customers found it so hard to believe she’d created the pieces she sold that they demanded to watch her work.

Many people probably found it equally tough to believe that Moses Fleetwood Walker integrated Major League Baseball (with the Toledo Blue Stockings) in 1884, 63 years before Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers. Or that Fleetwood also received patents in 1891 for an exploding artillery shell. Or that Moses Rodgers and other blacks owned highly productive gold mines outside Stockton.

Black History Month shouldn’t be an annual oldies roundup. It’s too rich, too varied and too surprising for that. It’s the many-layered saga of people who took what sometimes seemed like very little and turned it into more than enough — claiming their slice of an often elusive dream.

Betty DeRamus is the author of “Forbidden Fruit: Love Stories From the Underground Railroad” and “Freedom by Any Means: True Stories of Cunning and Courage on the Underground Railroad.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.