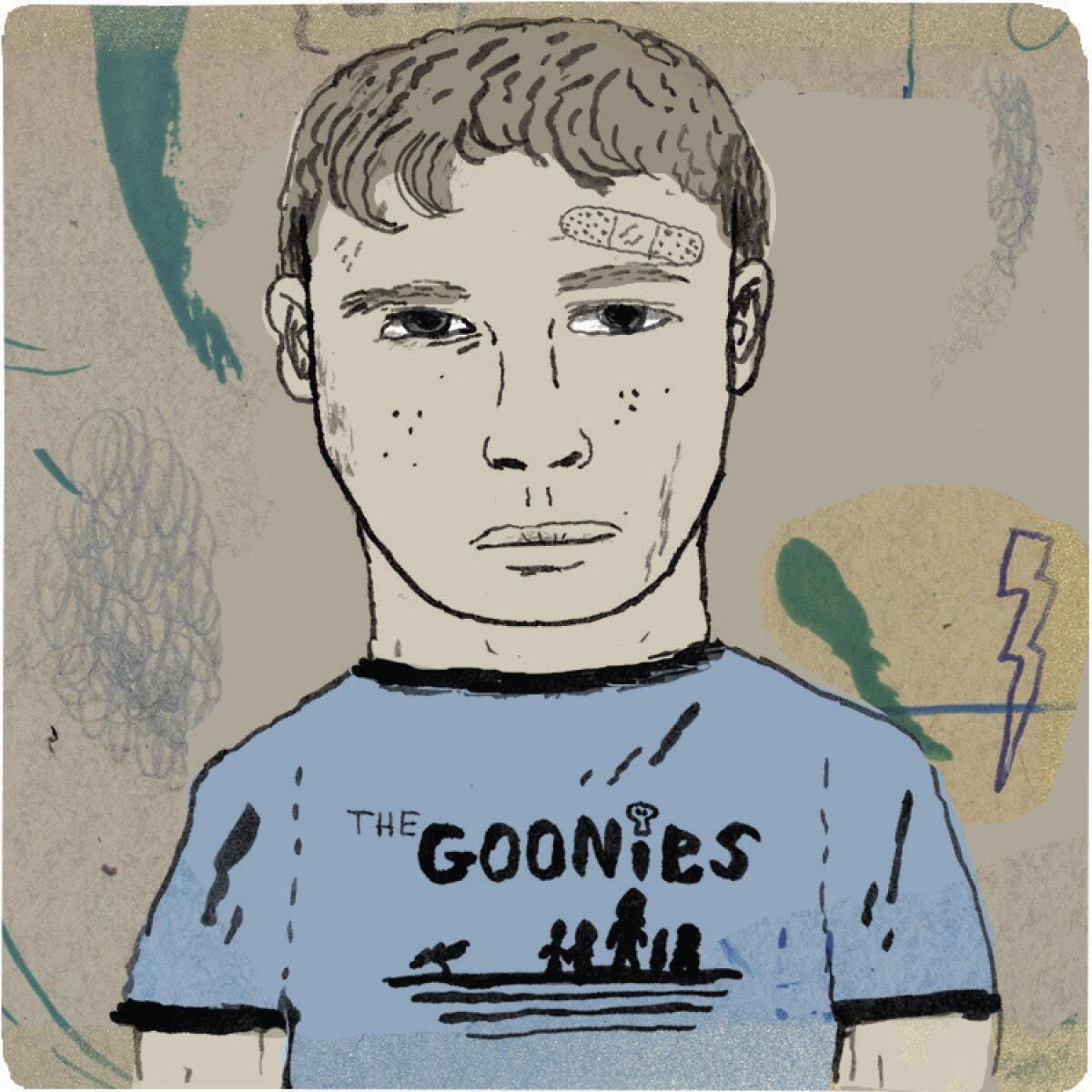

Broken homes, broken boys

When I started following the research on child well-being about two decades ago, the focus was almost always girls’ problems — their low self-esteem, lax ambitions, eating disorders and, most alarming, high rates of teen pregnancy. Now, though, with teen births down more than 50% from their 1991 peak and girls dominating classrooms and graduation ceremonies, boys and men are increasingly the ones under examination. Their high school grades and college attendance rates have remained stalled for decades. Among poor and working-class boys, the chances of climbing out of the low-end labor market — and of becoming reliable husbands and fathers — are looking worse and worse.

This spring, MIT economist David Autor and coauthor Melanie Wasserman suggested a reason for this: the growing number of fatherless homes. Boys and young men weren’t behaving rationally, they suggested, because their family situations had left them without the necessary attitudes and skills to adapt to changing social and economic conditions. Anyone interested in the plight of poor and working-class men — and, more broadly, mobility and the American dream — should hope this research, and the considerable biological and psychological evidence behind it, become part of the public debate.

Signs that the nuclear-family meltdown of the past half a century has been particularly toxic to boys are not new. As far back as the 1970s, family researchers began noticing that, although both girls and boys showed distress when their parents split up, they had different ways of showing it. Girls tended to “internalize” their unhappiness and were likely to become depressed and anxious. Boys, on the other hand, “externalized” or “acted out”: They became more impulsive, aggressive and “antisocial.”

Both reactions were worrisome, but boys’ behavior had the disadvantage of annoying and even frightening classmates, teachers and neighbors. Boys from broken homes were more likely than their peers to get suspended and arrested. Girls’ unhappiness also seemed to ease within a year or two of their parents’ divorce; boys’ didn’t.

Autor and Wasserman cite a large study by University of Chicago sociologists Marianne Bertrand and Jessica Pan, which shows that, by fifth grade, fatherless boys were more disruptive than peers from two-parent families, and by eighth grade, they had a substantially greater likelihood of getting suspended. And justice experts have long known that juvenile facilities and adult jails overflow with sons from broken families.

Liberals often assume that these kinds of social problems result from our stingy support system for single mothers and their children. Provide more maternity leave, quality daycare and healthcare, goes the thinking, and a lot of the disadvantages of single-parent homes would vanish. But the link between criminality and fatherlessness holds even in countries with lavish social welfare systems. A 2006 Finnish study of 2,700 boys, for instance, concluded that living in a non-intact family at age 8 predicted a variety of criminal offenses.

Even boys who don’t land in juvenile court find their prospects diminished. Several studies have concluded that boys raised in single-parent homes are less likely to go to college than boys with similar achievement levels raised in married-couple families; girls show no such gap.

So why do boys in single-mother families have a harder time of it than their sisters? If you were to ask the average person on the street, he would probably give some variation of the role-model theory: Boys need fathers because that’s who teaches them how to be men. The theory makes intuitive sense. And some evidence exists, though it’s far from settled, that boys who live with their fathers after divorce are better off than those who stay with their mothers.

As the sole explanation for the boy disadvantage, though, the role-model theory needs modification. If boys simply needed men in their lives to teach them the ways of the gendered world, then uncles, family friends, mentors, teachers, stepfathers and nonresidential but involved fathers could do the trick. It’s not clear that this is the case. And stepfathers have an especially mixed record in helping boys, the research shows. Professors Cynthia Harper and Sara McLanahan found that among boys they studied, the ones without fathers were more likely to be incarcerated, but they also found that those who lived with stepfathers were at even higher risk of incarceration than the single-mom cohort.

If the trends of the last 40 years continue — and there’s little reason to think that they won’t — the percentage of boys growing up with single mothers will keep growing. No one knows how to stem that tide. But by understanding the way family instability interacts with boys’ restless natures, educators could experiment with approaches that might improve at least some lives.

Educators and psychologists have often described boys as “needing clear rules” or “benefiting from structure.” Equally important is to find ways to improve boys’ literacy. Boys have always had greater difficulty learning to read than girls, and that holds across all socioeconomic levels and in every country where PISA scholastic tests are given to 15- and 16-year-olds. Kids having trouble reading too often become disengaged from school and drop out.

But the truth is, we don’t know for sure what will help. Our best bet is probably to follow the advice of social thinker Jim Manzi and start with small, controlled studies that lend themselves to careful evaluation — and keep experimenting.

Yet what also remains unknown is a possibility impervious to experiment. It just may be that boys growing up where fathers — and men more generally — appear superfluous confront an existential problem: Where do I fit in? Who needs me, anyway? Boys see that men have become extras in the lives of many families and communities, and it can’t help but depress their aspirations. Solving that problem will take something much bigger than a good literacy program.

Kay S. Hymowitz is a contributing editor of the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal, where a longer version of this piece appears. She is the author of “Marriage and Caste in America: Separate and Unequal Families in a Post-Marital Age.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.