Editorial: Google, books and ‘fair use’

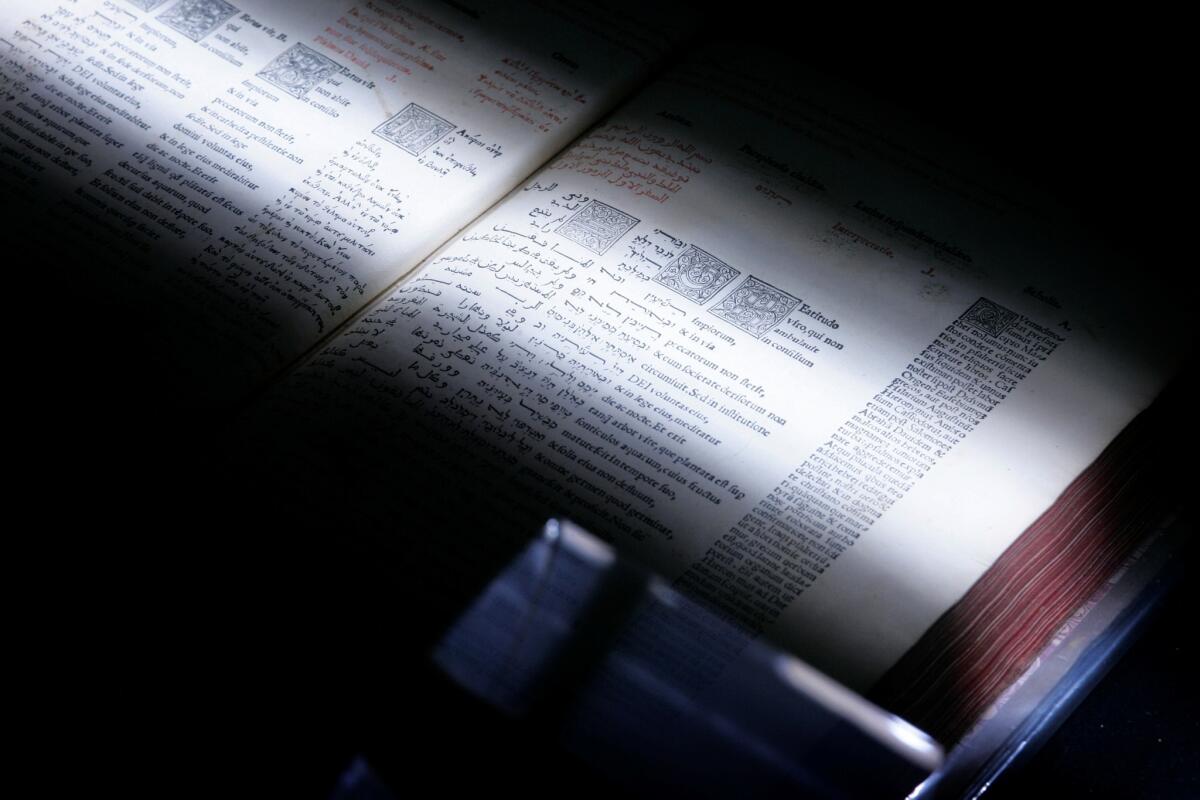

A scanner passes over a book in 2008 at the University of Michigan, where one of hundreds of librarians from all over the world was helping Google Inc.’s Book Search create digital versions of millions of titles.

Twelve years after Google shocked the book industry by announcing plans to copy millions of library books into a new online directory, the legal battle over the project has finally ended. The Supreme Court affirmed on Monday that Google can make copies for its index without obtaining the copyright holders’ permission or paying them for the privilege. Google’s wholesale copying may seem outrageous on first blush, but in the end, the court’s decision served the public’s interest — and the book industry’s.

Google’s book search project — begun in 2004 with the collections from five major libraries, then expanded to more than a dozen other collections — aims to make the world of physical books as easy to search through and, potentially, access as e-books can be. To do so, Google has scanned the pages of more than 25 million books, many of which were still copyrighted.

That copying drew lawsuits by authors and publishers, but the publishers eventually settled and the authors’ claim was rejected by two federal courts. By declining to hear the Authors Guild’s appeal, the Supreme Court left intact a decision by the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals that Google’s copying was a fair use. According to the court, Google transformed the books’ text into what amounts to a digital directory that points readers to books that contain the topics or phrases they’re searching for, along with links to the retailers and libraries that carry them. And by displaying only snippets of the scanned content, the online directory should promote demand for the volumes it indexes, not undermine it. That’s the right balance, although Google could do more to prevent searchers from circumventing the limits.

Some publishers have struck deals with Google to make larger samples available or to sell downloadable copies; others have instructed Google not to display any text from their works at all. Now it’s the authors’ turn to find their own ways to take advantage of the index Google has created. Meanwhile, a growing number of courts has held that copying works for the sake of making material easier to identify and find is legal. With fair limits on what can be displayed, those rulings should help innovative companies bring more of the world’s content closer to the people who’re looking for it.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.