Was adopting Common Core a mistake?

Think back to the dark days of 2009, when school districts in California and across the nation faced dire budget shortfalls. States would have done almost anything for extra money, and when the Obama administration dangled Race to the Top grants in front of them, many of them did indeed race to adopt the policies that would win federal approval — such as including student test scores in teachers’ performance rankings and adopting common curriculum standards.

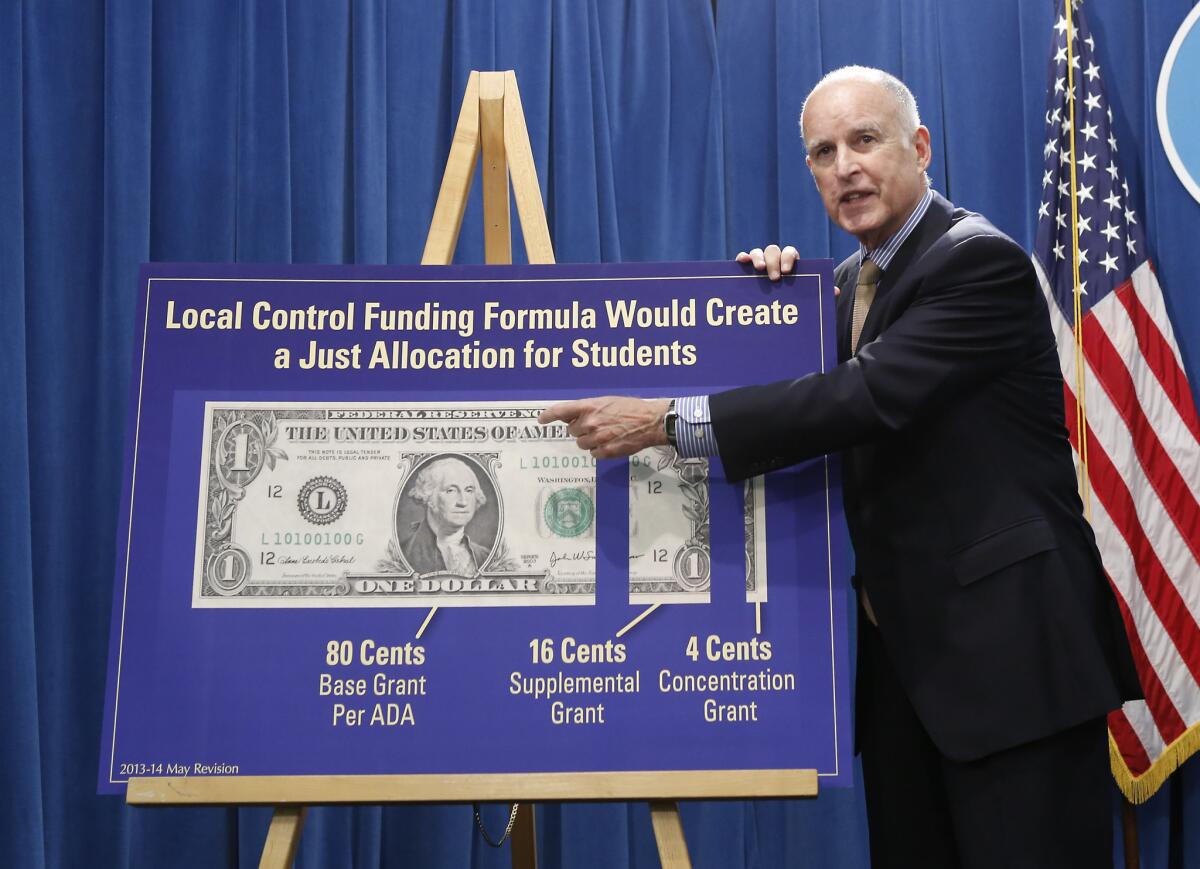

Because public education falls almost entirely under state authority, this sort of arm-twisting was the only way the administration could persuade states to do its bidding. The No Child Left Behind Act, the school accountability law adopted during the George W. Bush administration, also used money — federal Title 1 funding for disadvantaged students — to press its rigid standards on states.

Race to the Top pressured financially strapped states to adopt education policies that varied widely in their value. Many of the policies, such as the push to tie teacher evaluations to student test scores, were not backed by any sort of evidence. Yet they were adopted quickly because of application deadlines, and there was little time for thoughtful crafting of new rules.

EDUCATION: California Schools Guide

Yet for all the excitement, Race to the Top provided little actual cash. California would have received a one-time award of $700 million — less than 2% of what it spends on education every year. It failed to win a grant, but nonetheless had committed itself, as most states did, to the Common Core curriculum standards that the Obama administration supported. Implementing the standards, which are set to take effect in a year, will cost the state well over $1 billion.

Was adopting Common Core a mistake? A lot depends on how well it’s carried out. In theory, the new standards, which cover only math and English for the moment, look promising. They’re intended to foster more analytical thinking and polished writing — important preparation for higher education — and to minimize rote memorization. At the same time, there are valid concerns about mandates to reduce the amount of fiction read in English classes and about material that won’t be taught because of the focus on learning fewer subjects in more depth. Implementation so far has not been promising. Schools in New York state have been rattled by the start of Common Core-based tests even though the curriculum isn’t in place and the teachers haven’t been trained. As Los Angeles Times staff writer Howard Blume recently reported, there have been missteps in California, such as when schools in the Santa Ana Unified School District tried to start the new curriculum before the state had approved its own version or adopted instructional materials.

Now that the costs and complications of Common Core are becoming better known, both liberals and conservatives have expressed some buyer’s remorse. School administrators and teachers say it will be a long time before schools will be up to speed on the new curriculum, and that it would be unfair to judge schools and teachers based on the tests during the early years of implementation. Tea party Republicans complain about the federal government’s interference in curriculum, and a few states have withheld funding for the start of the new standards — though no one forced them into this to begin with.

Resistance among conservatives seems to be more about picking a winnable battle against President Obama than providing the best possible education for students. Concern that the rollout of the new standards is moving too fast for thoughtful, successful implementation is better grounded; we’d rather see a smoother, more successful implementation than further disruption in schools. In any case, test results during the first years should not be counted until teachers have gained training and experience in the new curriculum and the kinks have been worked out.

Whether Common Core will provide the promised results remains to be seen, but the ruckus over it — as well as over other reforms passed in an effort to win Race to the Top grants — shows this much: States are better off adopting new educational policies because they’ve been shown to work better for students rather than because they come with a financial prize attached.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.