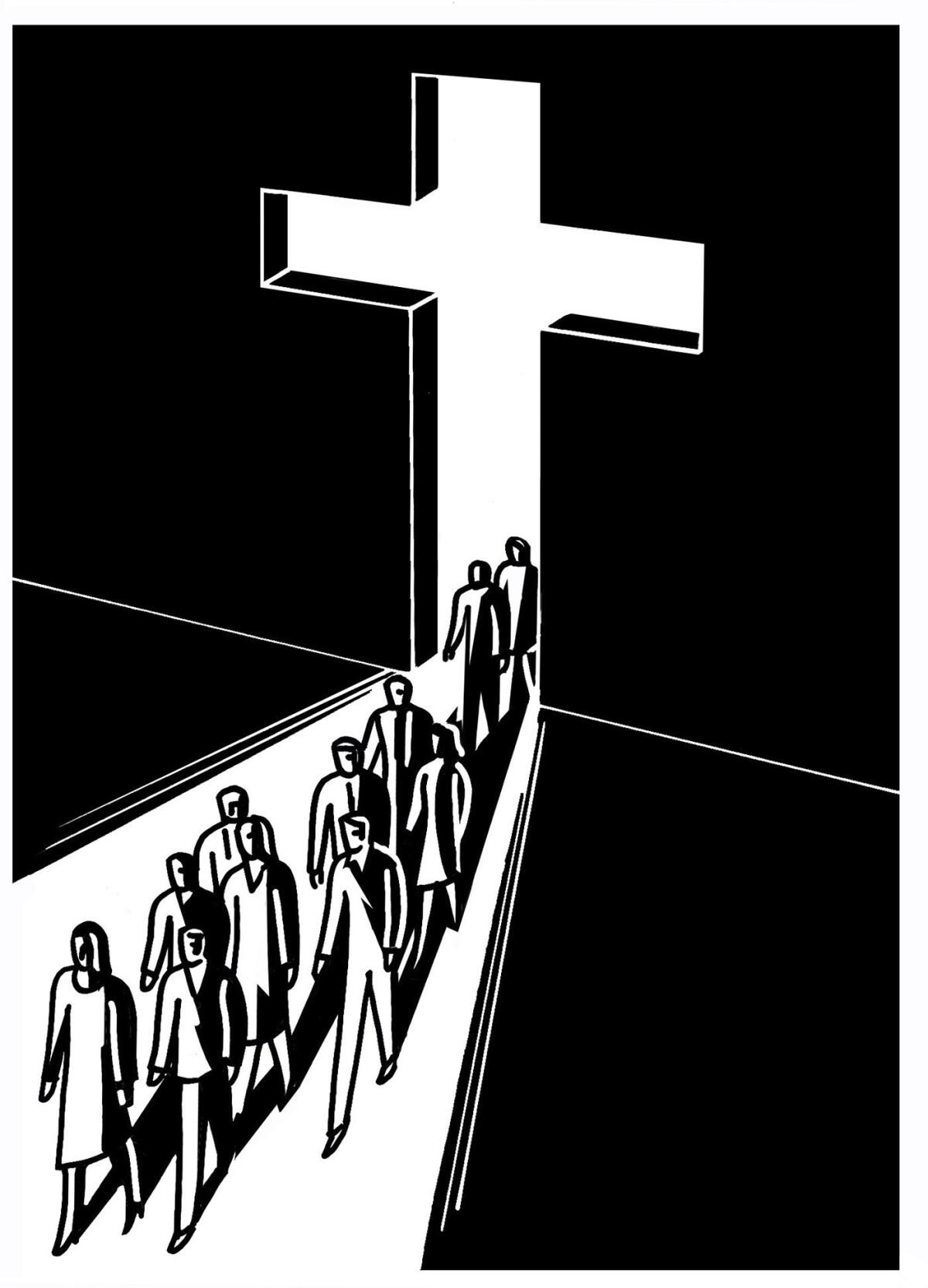

America’s evangelicals return to seeking souls, not votes

Only a decade ago, Christian social conservatives were a commanding force in American politics. They helped elect one of their own, George W. Bush, to two terms. They were a cornerstone of a GOP coalition that appeared to hold a permanent electoral majority. But today, the movement has lost its momentum — in part because one of its assets has become a liability.

It used to be that when Republicans wanted to increase conservative voter turnout, all they had to do was put same-sex marriage on the ballot. Even in liberal California, voters could be counted on to reject the then-outlandish idea of gay marriage.

But nothing in American politics has changed more rapidly than public opinion on that issue. These days, a solid majority of American voters say they don’t see anything wrong with gay nuptials. About the only major constituencies that haven’t come around are conservative Republicans and evangelical Christians, and even in their ranks, there’s a distinct generation gap. A recent Public Religion Research Institute poll found that while only 27% of evangelicals approve of same-sex marriage, 43% of evangelicals younger than 34 do.

That epochal shift has led to some soul-searching, not only in the Republican National Committee but among evangelical leaders as well. They are not abandoning their defense of heterosexual marriage and other conservative social causes. But they can’t help notice that the tide is moving in the other direction, and not just on gay marriage. Barack Obama defeated Mitt Romney in 2012 in part because he was able to tie the GOP candidate to socially conservative views on contraception.

The shifts in public sentiment have led Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention to draw an arresting conclusion: Contrary to what an earlier generation believed, there’s no “moral majority” in America today, and never was. “There was a Bible Belt illusion of a Christian America that never existed,” Moore told journalists at a conference sponsored by the Ethics and Public Policy Center last week. “The illusion of a moral majority is no longer sustainable.”

The Moral Majority, of course, was the Christian political caucus founded by the late Jerry Falwell in 1979. Falwell’s premise was that conservative Christians were a sleeping giant, and that if they were organized and summoned to the polls, Congress and state legislatures would do their will.

Moore has concluded that although plenty of Americans call themselves evangelicals and attend church most Sundays, many have drifted away from orthodoxy on issues such as divorce, abortion and gay marriage. To Moore, that means the crucial mission for believers shouldn’t be politics but rather to preach the Gospel and win souls.

“We will continue contending for the culture … but certainly not contending for electoral politics as the end goal,” he said.

Moore is no liberal; he believes in the literal truth of the Bible, and he abhors abortion and gay marriage. But he’s a realist. “We need to recognize where the country is,” he said.

For example, he said, attempts to put marriage amendments in state constitutions would be “a politically ridiculous thing to do right now.” Instead, evangelicals should focus on issues of religious liberty, such as whether Christian-owned businesses can be required to offer their services for gay weddings.

“I would want a presidential candidate who understands the public good of marriage,” Moore said, “one who is not hostile to evangelical concerns and who is going to protect religious liberty and freedom of conscience.”

Moore also thinks that, even as formal efforts to organize evangelicals politically wane, there is still plenty of room for faith leaders to promote policy changes that affirm human

dignity. This week, for example, he and Ralph Reed, chairman of the conservative Faith and Freedom Coalition, published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal criticizing the Republican-led House for failing to pass an immigration reform law.

“Their strategy is shortsighted,” the two conservative leaders wrote. “Reform is the right thing to do for our economy … and the moral thing to do for the soul of our nation.”

The Republican Party shouldn’t be too worried. Evangelicals are unlikely to leave the GOP even if they aren’t as active in promoting an agenda. In 2012, for example, 79% of white evangelicals voted for Romney, despite the unease some felt with his Mormon religion.

In fact, the refocusing of evangelical activism could actually be good for the party. In the next GOP presidential primaries, candidates may not face the same rigid litmus tests on social issues as Romney did. A candidate closer to the center of American public opinion — one, say, who accepts current laws on gay marriage and supports comprehensive immigration reform — might even survive the nomination process and get elected.

That wasn’t Moore’s objective when he took office last year as head of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. His goal was to find a more effective way to bring Christian belief into the public square. But he may also have made it easier for a moderate conservative Republican to run for president in 2016.

Twitter: @DoyleMcManus

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.