The Iran I saw — in 781 days in Evin Prison

On the morning of my appearance before an Iranian Revolutionary Court, where I was convicted on a fabricated charge of espionage, I heard the chant “Death to America!” from the world beyond my prison window. The chant, and the associated stereotype of Islamic Iran, was quite different from what I heard in Section 209, the grim area of Evin Prison where political detainees are beaten, tortured and held without charge. As Americans, my friend and cellmate Shane Bauer and I were denied contact with Iranian inmates during our imprisonment there. Yet time and again, they found the courage to defy that rule and lift our spirits.

When I’d sing anguished songs to the emptiness, I’d hear a knock of solidarity on my wall from an adjoining cell. Then another knock. Then a whisper from the hallway, and the soothing words in English, “We hope you become free!” Prisoners would hide candies in the washroom for us to find. I’d repay the kindness by sneaking chocolates, which my interrogators let me have, into the shower for my hall mates to discover.

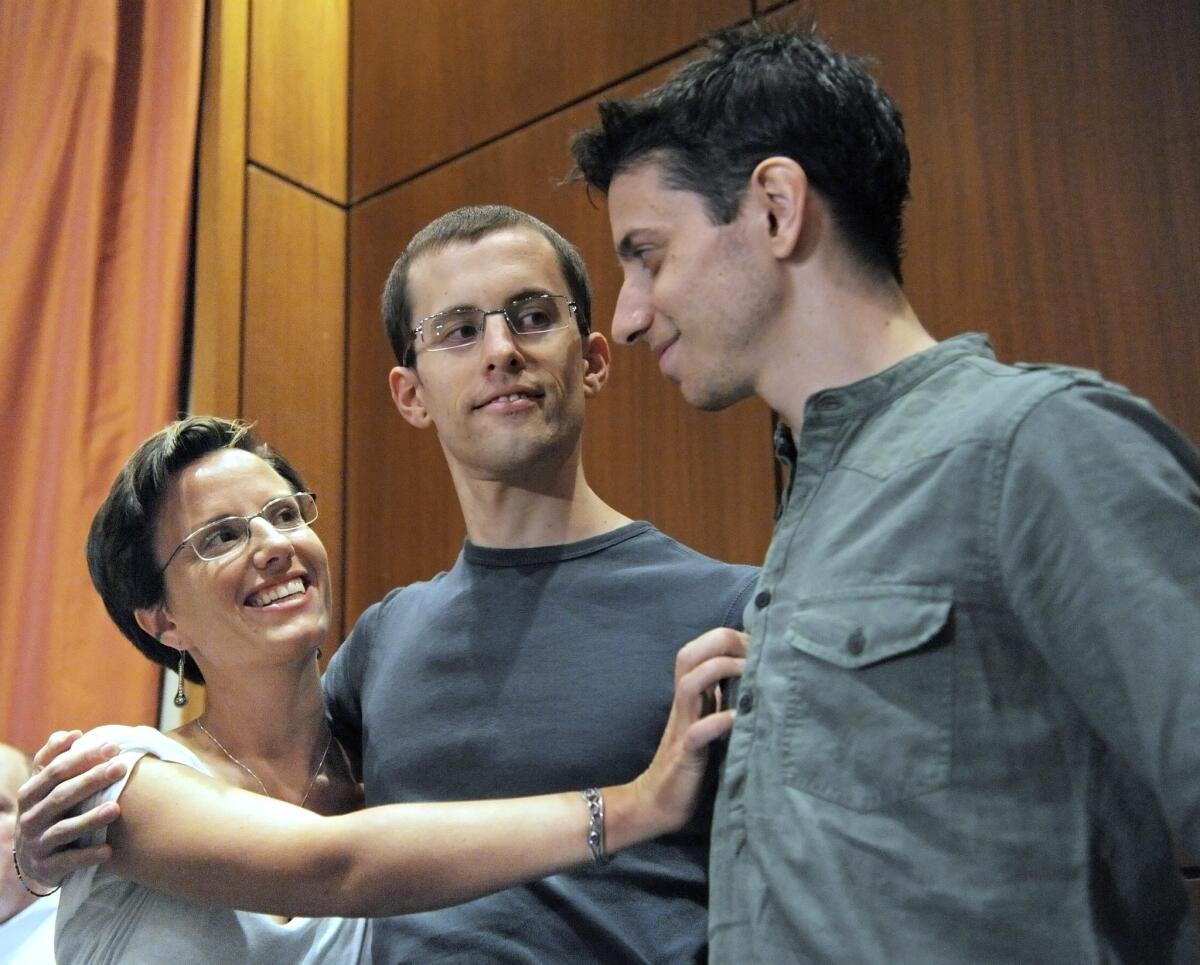

Over the 781 days of my incarceration, I developed a deep sense of solidarity with these Iranians. I landed in Evin Prison by happenstance in the summer of 2009. Shane and his girlfriend, Sarah Shourd, were living in Damascus, Syria, at the time, and I had gone to visit them after completing an international teaching fellowship. The idea of escaping the bustle of Damascus with a trip to the placid mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan appealed to us all. Without us knowing, our hike took us up to the unmarked frontier with Iran, where border guards detained us. Sarah was held for 14 months. Shane and I were held another year, until September 2011. Our captivity lasted longer than the Iranian hostage crisis.

In the weeks before our arrest, millions of Iranians had taken to the streets of Tehran in anger at the rigged reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. It was the largest popular protest since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and many of my fellow inmates at Evin were arrested during the demonstrations. The activists held in Evin were tortured and, in some instances, killed for seeking basic human rights. Yet they saw meaning in their condition. As one prisoner whispered secretly from the hallway, “Being in prison is a road to democracy.”

The so-called Green Movement that these jailed activists embraced wasn’t as easily crushed as the government would have liked. Though the popular protests died down, dissatisfaction over domestic issues, including the economy and restrictions on personal freedoms, remained high and became a major factor in last year’s presidential election victory of the reform-minded Hassan Rouhani. The fact that Iran’s clerical establishment allowed Rouhani to run and then engage with the United States was the result of this internal pressure for change. His election owes more to the inmates of Section 209 and to the millions of Iranians who have refused to accept the status quo than to the economic sanctions imposed from abroad.

In my mother’s letters to me in jail, she shared her conviction that my ordeal would lead to a diplomatic breakthrough between the United States and Iran. I liked the idea of something beneficial coming from my time behind bars. To me, life seemed to revolve around attempts to memorize poetry and to juggle dried oranges. She seemed incurably optimistic, like her reassurances in letters that I would be released “any day now.”

Yet my mother’s dream was not so far-fetched. Nine months into my detention, my interrogators led me blindfolded out of my cell to meet a man they described mysteriously as a “foreign diplomat from this region.” Awaiting Shane, Sarah and me in a prison office was Salem Ismaeli, an Omani businessman and envoy of Sultan Qaboos bin Said. He enveloped us in his flowing robes as he introduced himself, and I still remember how sweetly he smelled of sandalwood. He gave us expensive watches and told us his mission was to get the United States and Iran to talk to each other about our release.

It took more than a year for Salem to deliver us to freedom and the waiting arms of our families on the tarmac in Muscat. The Associated Press has since reported that Oman’s mediation led to direct talks between U.S. and Iranian officials that paved the way for last November’s interim accord to freeze parts of Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for relief from some economic sanctions.

With talks between Iran and six world powers on a permanent accord resuming this week, some voices in Congress and some supporters of Israel continue to warn against engagement with Iran and to press for even tougher sanctions. The Iran that I glimpsed under my blindfold, heard in the supportive whispers on my prison hallway and tasted in the sweet candies provided by my hall mates convinces me this stance is misguided.

It is time to end the mutual hostility for good. A permanent accord that limits Iran’s nuclear capabilities in exchange for a lifting of sanctions would make my relatives in Israel safer. It would make my family in the United States safer. And it would strengthen the hand of the brave Iranians I met in the dark corridors of Evin Prison in their continuing struggle for democracy.

Josh Fattal is the coauthor with Shane Bauer and Sarah Shourd of the forthcoming memoir, “A Sliver of Light: Three Americans Imprisoned in Iran.” https://www.joshfattal.org

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.