Senate Democrats rewrite the filibuster rule. Now what?

The sight of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) using procedural legerdemain to weaken the filibuster rule Thursday must have sent Robert C. Byrd spinning in his grave.

The late Democratic senator from West Virginia was a stickler for Senate traditions and a staunch defender of the procedural kinks and quirks that make it so different from the House. The filibuster rule is Differentiator No. 1 because it prevents the majority party from running roughshod over the minority, which is how the House rolls (and not to its credit).

Forget the romanticised, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” vision of the lonely filibusterer talking until he or she topples over from exhaustion. The real power the rule grants is to groups of 41 or more senators, enabling them to keep a debate going indefinitely on a nomination or a piece of legislation. The practical consequence is that any major nominee or bill has to reflect something approaching a consensus to advance. And that’s a good thing.

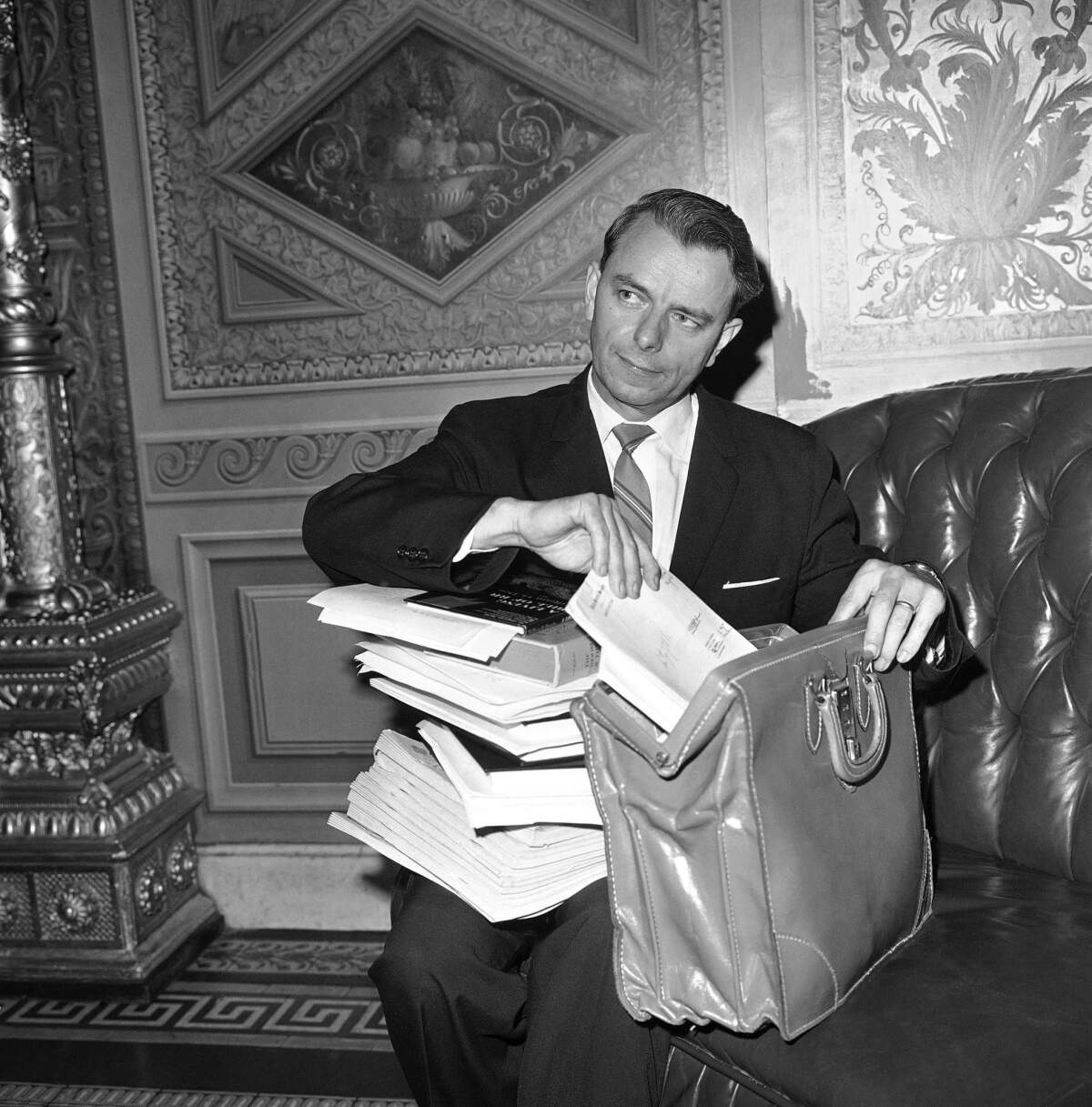

PHOTOS: Famous filibusters (and a bonus -- a recipe for fried oysters)

In recent years, though, the filibuster has become routine, robbing it of meaning. To paraphrase Syndrome, when everything’s major, nothing is. Hardly a day went by without a Senate Republican threatening to filibuster something, no matter how unimportant or widely supported. The chamber couldn’t even begin debates, let alone cut them off, unless 60 members agreed. Reid played hardball too, routinely using procedural techniques to prevent Republicans from amending bills or forcing votes on hot-button issues.

Still, the Senate has always been a difficult place to get things done. And cooler heads typically prevailed. With the House GOP pushing that chamber far outside the political center, the Senate has been the place where compromises have been struck and impasses have been resolved. Here’s a recent example: The deal that settled last month’s government shutdown grew out of the work done by a small, bipartisan group of senators.

The question now is whether eliminating the filibuster on judicial nominees (an exception that does not apply to Supreme Court nominees -- yet) will move the Senate inexorably toward the sort of House-like majority-party domination that Byrd feared. Will Republicans dig in their heels even deeper on legislation, prompting Reid to try to change the Senate rules again to end filibusters on those measures too?

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has said Democrats would soon rue the rules change. And there’s plenty of reason to expect Republicans to retake the Senate in the 2014 elections -- not because voters will care more about judicial nominees than they already do but because the Affordable Care Act is so unpopular, the economy is still sluggish and President Obama’s plunging favorability ratings weigh heavily on vulnerable members of his party.

So it will be interesting to see how many nominees Obama tries to push through the Senate over the next year, while Democrats still have the majority. A rush to fill vacant seats would only further irritate Republicans, spelling trouble for efforts to keep the government open, raise the debt limit and find an alternative to the deepening across-the-board sequester cuts.

Not that those issues weren’t challenging enough already.

Reid had been in Byrd’s camp for years. Even when he’d threatened to change the filibuster rules to overcome GOP opposition to presidential nominees, the threat was clearly coming from frustrated Democrats to Reid’s left, not him. He seemed to remember when the shoe was on the other foot and Democrats were using the filibuster to block a number of President George W. Bush’s nominations. That’s why he settled for a series of deals with Republicans that left the filibuster rule intact in exchange for a promise that obstruction would be the exception, not the rule.

Perhaps he changed his mind because he felt Republicans were calling his bluff. The latest nominees blocked by GOP filibusters included one clunker -- Rep. Mel Watt (D-N.C.) to oversee Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, a position that would seem to demand an experienced financial regulator, not a politician -- but Obama’s three picks for the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit were well respected.

What Reid saw as obstruction, however, Republicans simply viewed as payback for Democrats blocking Republican nominees for the very same court, ostensibly for the same reason (too small a workload to justify filling the vacancies). And as with any bitter gang war, Reid just escalated the tit-for-tat squabbling, all but guaranteeing retaliation by the next GOP Senate majority.

ALSO:

Harry Reid busts the filibusterMcManus: Obama’s reversal of fortune

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey and Google+

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.