At the Supreme Court, little love for an antiwar protester

Protesters are a pain for government in general, and the Pentagon in particular. But the armed services ought to be able to suck up a protest even on land that is part of a military base so long as it’s nonviolent and doesn’t pose a threat to security.

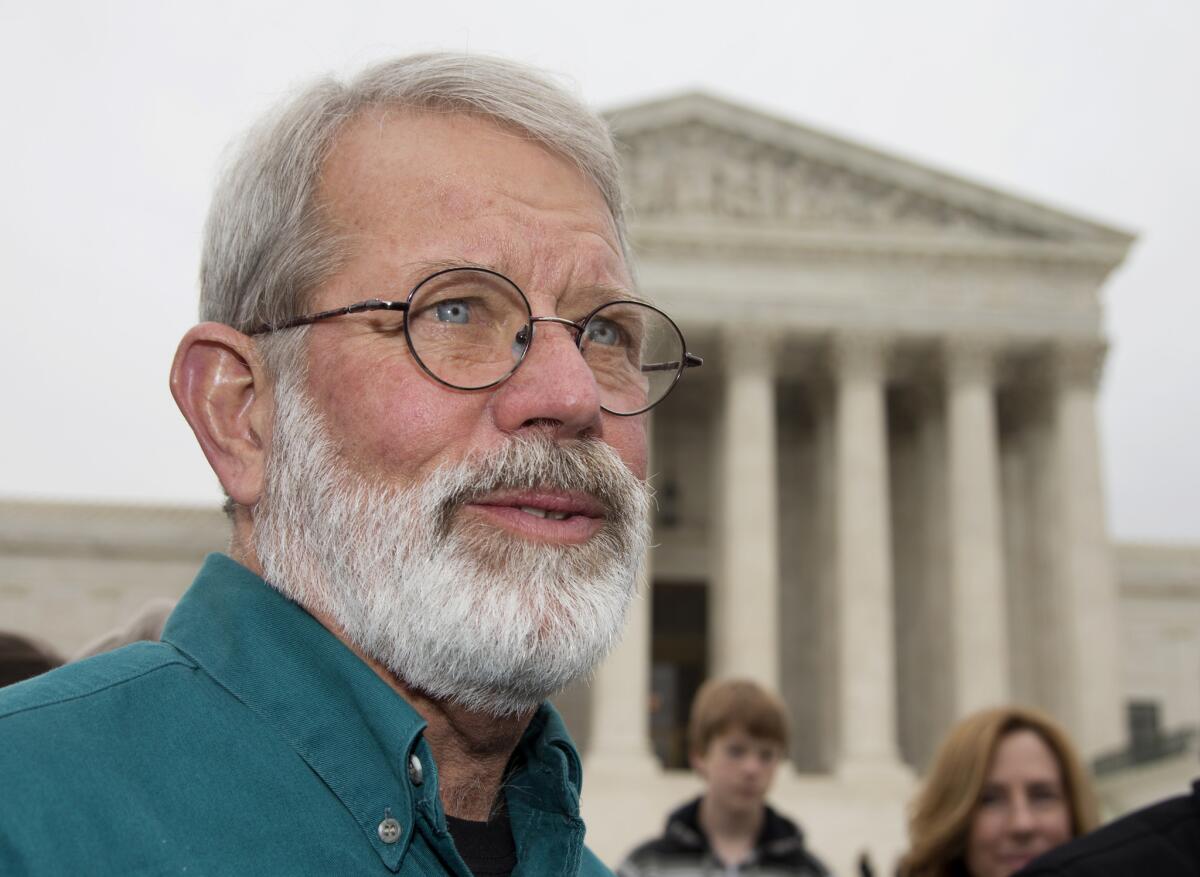

That was my takeaway from arguments in the Supreme Court on Wednesday arising from the conviction of antiwar protester John Dennis Apel. In 2010, Apel engaged in a peaceful protest on a stretch of Pacific Coast Highway that passes through Vandenberg Air Force Base. The problem was that he was violating an order barring him from the base for vandalism (on a previous occasion he had thrown blood on a “welcome” sign at the base) and trespassing.

Alas, the justices weren’t focusing on the wisdom of the Air Force in going after Apel or even on whether his constitutional free-speech rights were violated. (“You keep sliding into the 1st Amendment issue,” Justice Antonin Scalia told Apel’s lawyer, Erwin Chemerinsky. “You can raise it, but we don’t have to listen to it.”)

YEAR IN REVIEW: Washington’s 5 biggest ‘fails’ of 2013

Rather, the issue was whether the road where Apel protested was a part of Vandenberg for legal purposes, meaning that he could be excluded from it. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled for Apel on the grounds that the Air Force didn’t have exclusive possession of the area; it shares practical control with state and local authorities.

But most justices seemed to have a problem with that argument; the military provides access to lots of people to its installations while retaining ownership. Justice Stephen G. Breyer cited the example of a public utility worker who comes on to the base to read a meter. He asked Chemerinksiy if that meant protesters also had to be admitted to “the heart of the military base.”

Chemerinsky argued that the “United States wants it both ways” because it claims control over the road where the protest took place but allows the state to maintain the road. To which Scalia replied: “They’re entitled to have it both ways. It’s their base.”

So it doesn’t look as if the court is going to rule in favor of Apel, and that may be the right resolution of the legal issue. But this case shouldn’t have been brought in the first place. Not only was his protest peaceful, it took place in an area that had been designated a protest site as long ago as 1989. His conviction violated the spirit if not the letter of the 1st Amendment.

ALSO:

The righteousness in Hobby Lobby’s cause

What Obama should do if he wants young people to sign up for Obamacare

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.