Op-Ed: Sex trafficking defendants have a new face — white, wealthy and well-connected

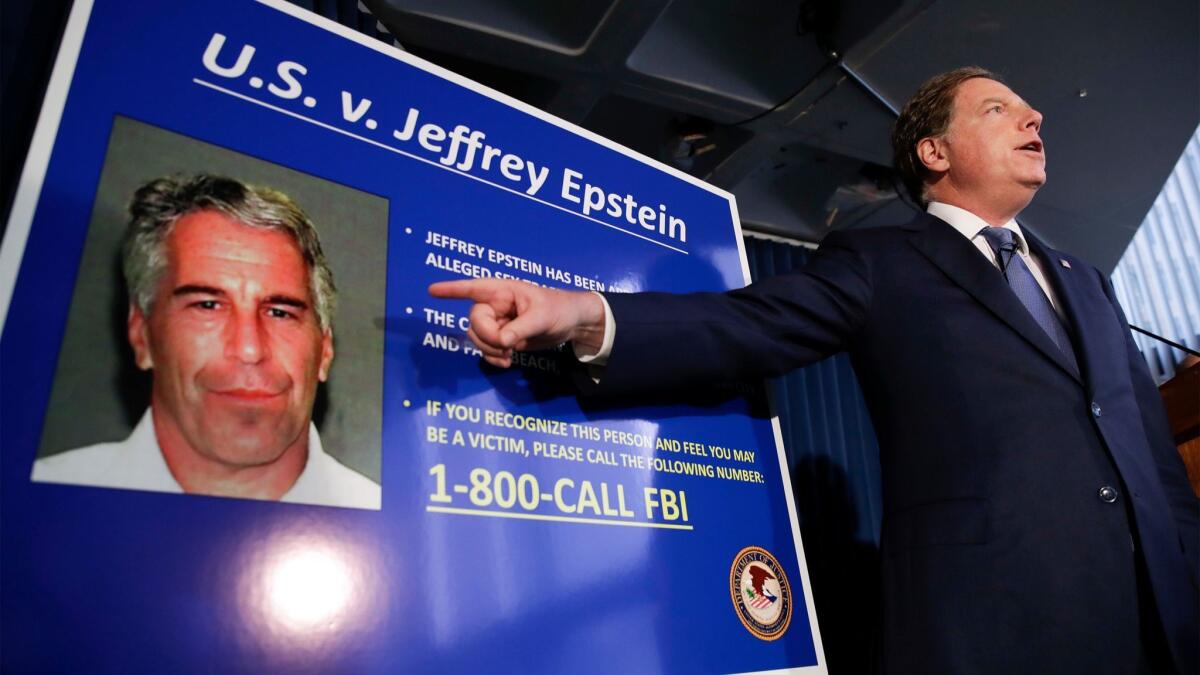

The new faces of sex trafficking are increasingly white, affluent and well-connected. In an indictment unveiled July 8 in the Southern District of New York, Jeffrey Epstein, the wealthy hedge fund manager, was charged with sex trafficking for recruiting numerous minors for paid sex acts. In 2018, a federal judge ruled that Harvey Weinstein, the film producer, could be sued under the federal sex trafficking law for allegedly coercing a woman to engage in sex in exchange for promises of job advancement.

This shift is an important development, as anti-trafficking efforts have long been criticized for their disproportionate focus on communities of color. Powerful men are now being brought to account in courts across the country for an increasingly diverse array of wrongful conduct.

This is undoubtedly due, in large part, to the growing strength of the #MeToo movement. But it also has much to do with the evolution of human trafficking law in the United States. Sex trafficking is a relatively new, but very powerful legal concept both in the U.S. and under international law. Over the past two decades, anti-trafficking law has gained momentum. It has also proven to be remarkably elastic, as it has been used against varied actors and conduct.

The basic idea of trafficking emerged in the early 20th century in close association with notions of “white slavery,” which was largely defined as the forced prostitution of white European women. In the United States, such racialized narratives remained center stage, as foreign national and African American men were often targeted for federal prosecution, and the media commonly portrayed trafficking as a problem connected with gangs, poverty, and inner-city violence.

However, in recent years, societal attitudes have shifted. Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act in 2000, establishing federal sex trafficking crimes and important federal protections for victims of trafficking. Congress defined the federal crime of sex trafficking to mean using “force, threats of force, fraud or coercion” to induce another person to engage in a commercial sex act. Contrary to popular belief, transporting the alleged victim is not required under this law, and a “commercial sex act” is simply performing sex in exchange for anything of value.

Since then, Congress has adjusted the federal framework to provide prosecutors and civil litigators with still more powerful tools. In 2003, it empowered victims of trafficking to file federal civil suits against perpetrators. This has opened up avenues for new parties to be targeted with civil and criminal liability, and in 2015, Congress passed legislation relabeling certain buyers of sex as perpetrators of trafficking. Soon after, in 2018, the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act was passed to extend civil and criminal liability to online platforms that facilitate sex trafficking.

Creative litigators increasingly file civil cases that seek to expose new parties, including hotels, doctors, and websites like Backpage.com, to mounting civil liability. In other cases, such as Weinstein’s, plaintiffs have sought to frame sexual abuse as trafficking to secure damages under the federal trafficking law. In addition, 50 states have now passed human trafficking statutes, some with surprising breadth. For example, certain states, such as Massachusetts and Minnesota, have statutes that eliminate the requirement of force, fraud or coercion altogether. In these states, harboring, recruiting or obtaining someone for the purpose of commercial sexual activity is sufficient alone to amount to sex trafficking.

There is much to applaud about these developments. Epstein’s arrest, like that of Harvey Weinstein, signals a move toward justice for victims of sexual violence. But it is less clear whether trafficking can — or should — be the legal tool used in prosecuting all kinds of cases involving sexual abuse by the powerful.

We should also be wary of the collateral consequences of stretching the concept of trafficking too far, perhaps eventually to its breaking point. The elasticity of trafficking has allowed it to be marshaled against a vast array of conduct. This allows the concept to be easily — perhaps in some cases too easily — deployed by politicians and prosecutors who want to appear “tough on crime” or use allegations of trafficking to mobilize public condemnation against a wide range of conduct.

This has been all too apparent in President Trump’s crusade against “trafficking,” which he has used to garner support for his border wall and failed asylum policies. Federal officials have also invoked concerns about trafficking as one of the justifications for the disastrous “zero tolerance” border policy that resulted in thousands of separated families.

As the trafficking concept broadens, it also risks ensnaring victims and other collateral parties, targeting them with more severe federal penalties and disproportionately impacting communities of color. And this trend may make it more difficult to move effectively against defendants like Epstein, whose alleged conduct it was clearly meant to punish.

The moral condemnation associated with trafficking can only be channeled in so many directions without becoming diffuse or sowing confusion. Tarana Burke, the founder of the #MeToo movement, perhaps put it best when commenting about the expansive use of #MeToo: “It is hurting the work we’re trying to do. Because you can’t cover so much, and so many things.”

Anti-trafficking law is an important part of the legal arsenal. But if trafficking becomes a catch-all for prosecution of sexual violence, it risks losing its power.

Julie Dahlstrom is a clinical associate professor of law at Boston University, the director of the Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program, and the author of the forthcoming law review article “The Elasticity of Human Trafficking.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.