Opinion: 2020 candidate Seth Moulton on how Democrats are ignoring common sense in the fight against Trump

- Share via

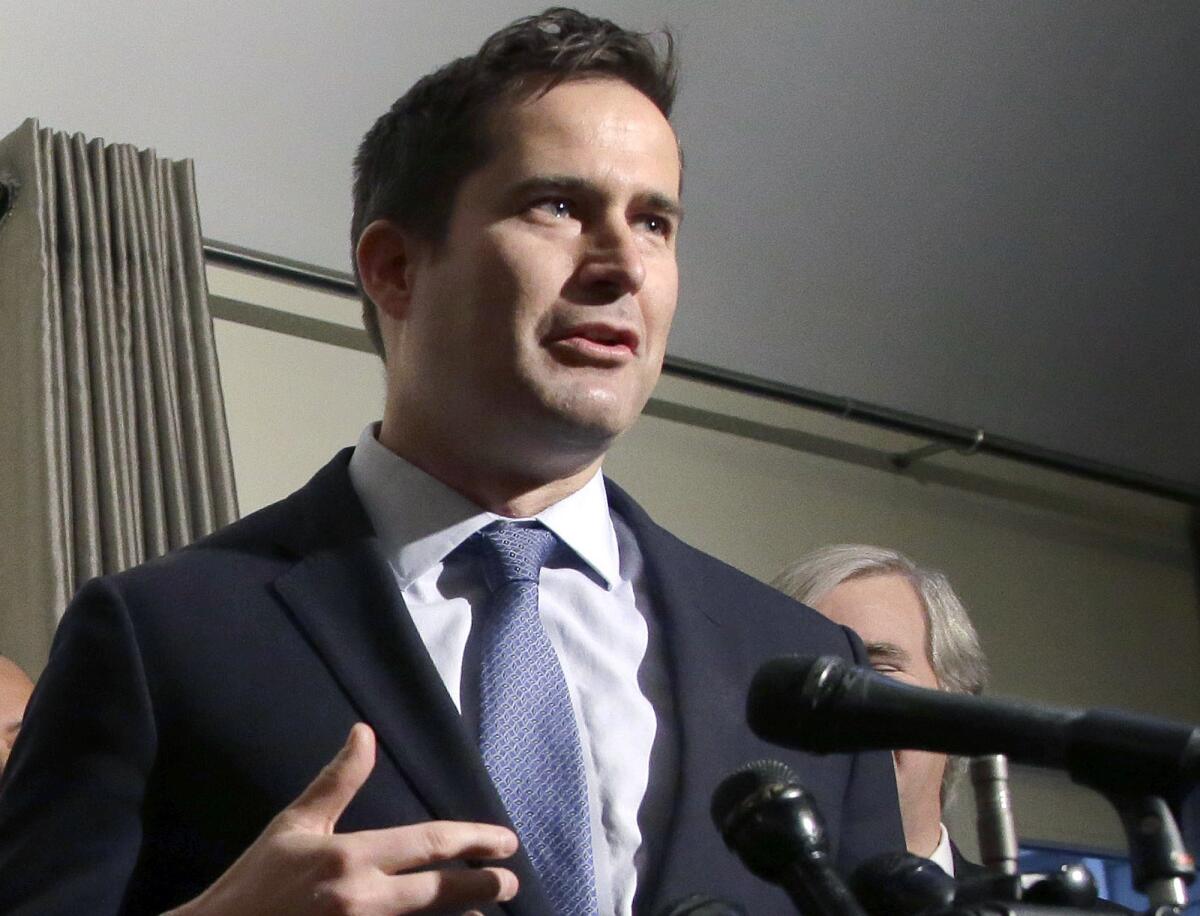

Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), a candidate for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, sat down with members of the Los Angeles Times editorial board to discuss his underdog presidential campaign. The following is a transcript, lightly edited for clarity.

Nick Goldberg, editorial pages editor: So why don’t we hand you the floor for not too long, not to monopolize the whole hour, but for, you know, a five-minute intro if you want to tell us what’s on your mind or why you’re running or why you’re here.

Rep. Seth Moulton: Sure. So why don’t I just start from the beginning, since I didn’t expect to even be in politics, let alone running for president at this point in my life, and explain just how I got here. I wouldn’t be in politics period if not for my time in the Marines. It was in Iraq that I felt like I saw the consequences of failed leadership in Washington and ultimately decided that I wanted to be a part of trying to change that and preventing something like Iraq from happening again. The reason I went into the Marines more than anything else was the most important mentor I’ve ever had in my life, who was the minister of my college church at Harvard. His name was Peter Gomes. He was this larger-than-life moral figure on campus, in addition to being the school minister. He talked a lot about the importance of service, and he challenged his students to not just support those who serve or believe in the value of service, but actually go out and find a way to give back. So I looked at different options as I was approaching graduation — Peace Corps, teaching overseas — but ultimately had so much respect for the 18-year-old kids who put their lives on the line for our country that I decided that that’s where I would do my part.

So going into the military, I knew I wanted it to be in the infantry on the ground. I said, you know, I don’t want to be riding in a truck while some kid is slogging through the mud next to me, but I didn’t have any particular connection to a service or whatnot, so it took me awhile to decide between the Army and the Marines. I certainly had no idea that Sept. 11 was going to happen three months after I graduated, or that a year after that I’d end up in the first company of Marines into Baghdad or do a total of four tours in that war.

But in addition to seeing some of the consequences of failed leadership in Washington, when I was in Iraq, I felt like I saw the best of America in the worst of circumstances. My job as an infantry platoon commander leading combat troops on the ground was fundamentally to bring this remarkably diverse group of Americans, people from all over this country — including several from around here — with different backgrounds, different religious beliefs, different political beliefs and get them all united behind a common mission to serve America. In a lot of ways, I think that that is exactly the leadership that we need both from our nominee and from the next president of the United States, because we have to bring America together if we’re going to build the diverse coalition we need to win. And the coalition we need to beat a sitting, incumbent president with a decent economy is a coalition that includes everybody in the Democratic Party. You can’t leave anybody out. Plus, independent voters, those Obama-Trump voters and even some disaffected Republicans. I’ve built coalitions like that in very divisive circumstances before, in the middle of a war that I was an outspoken critic of.

I also think that after we win, the only way we’re going to get anything done, you know, pursue this ambitious agenda that you see coming out of this field, is to find some unity in the country. More unity than we have now. I certainly have never seen America more divided than it is today. So when I got to Congress back in 2014, having no background in politics whatsoever, but just wanting to serve the country in a different way, I really focused on just being a good member of Congress. I was named the most effective freshman Democrat, held more town halls than any other Democrat in the country, House or Senate, you know, just sort of, you know, won a bunch of awards for being the most transparent office on Capitol Hill and being the most tech-forward office, which my friends always remind me is a very low bar [laughs], so not much of a big deal.

Mariel Garza, editorial writer: I think it’s lower in the Senate [laughing].

Moulton: Yeah, that’s true. But just really trying to do a good job. When 2016 happened, it woke me up to the responsibility to get more involved in the political side of the job, to actually try to change Congress. So I spent two years, from 2016 to 2018, working hard to flip the House, focusing on the districts we needed to win back, and focusing on veterans who were not only in sort of my niche because of my background, but also people who tend to do very, very well in those types of districts.

Of the 40 or so seats that we flipped to take back the House, over half of them were candidates that I supported, in many cases recruited, campaigned with. This wasn’t like most members writing a $5,000 check. Conor Lamb, I raised $183,000 for, for example, in his race in western Pennsylvania. And I was one of the, was one of only four Democrats nationwide that he even invited to come campaign for him on the ground. When Amy McGrath ran and narrowly lost a House race down in Kentucky — she’s now running against Mitch McConnell — she only invited two Democrats to come and campaign for her: Joe Biden and myself.

So I’ve been to a lot of places in this country that Democrats don’t often go, but the kind of places that we need to win if we’re going to expand the map, and the sorts of swing states that we need to win if we’re going to win this election. And you know what? We have an incredibly talented Democratic field. And you might ask, “OK, Seth, you know, if it’s so important to beat Trump, why don’t you just get behind someone else in the race who got in earlier than you, who’s ahead of you in the polls or something?” If I honestly thought that there is another one of the 24 or 25, whatever it is that are running, that would be better at going against Trump than me as a young combat veteran, and the only one in the race, then that’s what I would do, because I think it is incredibly important that we beat this guy, and I think he’s going to be very difficult to beat.

Garza: Why would you be better than the others?

Moulton: Because I think that there’s two things Americans really want, and it shows up in the Democratic polling, but it also shows up in what I hear on the campaign trail. They want a new generation of leadership, and that’s something I’ve not only talked about but literally fought for since I came to Congress and beat an 18-year incumbent to run. They want someone who is willing to not just represent a younger generation, but be willing to challenge the system and take on the power structures in our party and in Washington that have gotten us where we are. But second it’s got to be someone who just can go toe-to-toe with this guy on the debate stage and build this coalition that I described that I think we need to win. I just think that I’m better qualified to do that, because I’ve done this in some of the most difficult circumstances on Earth, than anyone else in the race.

Goldberg: We haven’t seen you on any debate stages.

Moulton: That’s right. You haven’t. I got in late because I have a 9-month-old daughter at home, and it simply wasn’t an option for me to get in when she was 2 or 3 months old, and Liz and I are first-time parents. So I recognize that the getting in late has been a handicap.

Goldberg: But you said Americans want to a candidate who can go toe-to-toe on the debate stage. What indication or evidence do we have that you’re that person?

Moulton: It wouldn’t be the hardest thing I’ve done in my life. I’ve done much harder things before and I’ve done it in more difficult environments. And frankly a young combat veteran standing up against Trump, someone who dodged the draft to avoid serving in his generation’s war, I think is a really good foil, especially for winning the independent voters that we need to take this election.

Now listen, if you think that anyone in this on the debate stage or in this race can beat him, then have at it. Just pick the flavor of the month or whatever. I think he’s going to be hard to beat. I think that for a few reasons. One, because going to these districts like Conor Lamb’s district, like Kentucky to campaign for Amy McGrath, you realize that his support is a lot deeper than people realize. It’s especially deep in the swing districts that matter.

I get the fact that in Massachusetts, in New York, in California, he’s super unpopular and that’s how he loses the popular vote. But in the places that we have to win back, he’s got a lot of support. I also think he has a lot of quiet support. I’m shocked by the number of people who completely acknowledge that he is a terrible guy, he lies all the time, he is immoral, he’s not a role model for our kids. But they say, “You know, we like his policies.”

Garza: How do you challenge that?

Moulton: Well, it’s a really good question, because I think that what the Democratic Party has been doing so far is, we’re pulling our hair out telling everyone what a terrible guy he is. You know, “Can you believe he said this?” He’s this, he’s that. He’s immoral, he’s racist, all this stuff, right? And it’s all true.

But basically we’re suggesting to all his supporters that they’re such idiots that they can’t figure this out. And I think that’s wrong. I think they know. ... I mean, look, there’s millions of different views in America. You can certainly find people who actually do think he’s a good guy, but I think most people recognize that he’s not a great guy, but he’s willing to challenge the system. He’s willing to upend the system and, hey, the economy is doing OK. You know, why would we change that? Why would we go back for something that we have already — I also think that the Democratic Party has not presented, as a party, a very good alternative to what Trump presents as president in the eyes of some of these independent voters that we need to win.

And by the way, there’s also an argument that we just need to drum up the base, but that didn’t work in the midterms. The New York Times detailed last weekend how that’s really not going to work here. If you want to get to some of those independent voters, then I don’t think we can be a party that is going to force everybody to go on a single-payer government healthcare plan, which, by the way, wouldn’t even have enough votes in a Democratic-controlled House right now to pass.

So not only is it, I don’t believe, the right plan for Americans, and I’m happy to go into that; I say that as the only candidate in this entire field that actually gets single-payer healthcare, because I go to the VA for my healthcare, and I don’t think that’s a system that every American is going to want. But on top of that, it’s an empty promise because it’s never going to pass.

I don’t think that we can be a country that says there is no penalty for crossing the border illegally. It’s not even illegal in fact. I mean, a country has borders, and I’ve been a huge advocate for immigration reform. I’m probably the only candidate in this race who’s actually, my family has taken in a refugee seeking asylum and who has lived in our home. OK, so I get this. I care about it a lot. We help people all the time, through my congressional office, [to] stay here. And I’ve helped numerous people, mostly from Morocco and Afghanistan as translators come here to the United States.

I think immigration is essential. I think it needs to be reformed. I mean, don’t get me wrong, but I also believe that we have to be a country of borders. I don’t want a system that incentivizes people to come here illegally rather than legally. I think that most Americans kind of see that as common sense, and yet that’s not where the Democratic Party is headed.

I think that everybody in the world deserves healthcare because it’s a human right. Whether you’re someone dying of diabetes in Appalachia or you’re a migrant dying of heat exhaustion in the desert, you deserve healthcare, and a decent country would take care of you. But I also think that it has to be a priority to take care of our own people first. We’re obviously not doing that today. That kind of common sense approach is just, I don’t think something that you’re hearing from the party writ large.

By the way, you’re also not hearing from the party a willingness to do the tough work, to actually hold Republicans accountable, because we refuse to even hold hearings on impeachment when the president has very clearly violated the law. You know, my motto in the Marines, actually when I served under Gen. [Jim] Mattis as the 1st Marine Division commander, our motto was, “No better friend, no worse enemy.” If you’re going to be a good friend to the United States, to the Marines, we’ll treat you better than anyone else, but we’re also going to stand up to you if you’re not. And right now, the Democratic Party isn’t doing either. I mean, we literally attack our own, right? It was our party leadership that went after the Squad, as they’re called, before Trump did. In fact, he was like a wolf bouncing on a bunch of sheep that had been separated from the flock. We literally attack our own, and we’re not willing to hold the president accountable when he’s so flagrantly violating the law.

I think our unwillingness to do that will be viewed very poorly in the light of history. You know, when [my daughter] Emmy is 20 years old and sitting in college reading the history books about what happened when Donald Trump was doing all these things and it was a feckless Democratic Party unwilling to just do our constitutional duty and hold impeachment hearings, I don’t think that’ll be viewed well.

Goldberg: What law is it that the president flagrantly broke?

Moulton: He’s clearly committed obstruction of justice. If you simply read even just the executive summary of the Mueller report, you can see Mueller has very clearly said, “I can’t indict him, but this is Congress’ job to hold these hearings.” I also think the most important conclusion of the Mueller report overall is that Russia clearly influenced our elections. We have a commander in chief who’s not only absolutely denying it, listening to Putin over American intelligence agencies, but he’s doing nothing to protect the country. That should be something that Congress seriously investigates, because I do think it’s dereliction of duty by the commander in chief, but most importantly, it’s just a national security issue for the entire country. Whether you’re a Trump fan or you’re a Trump hater, you should want to know the answer to that.

Robert Greene, editorial writer: You said there were a lot of people who think he’s a terrible person, but like his policies and are quietly going to probably vote for him again. So apart from obstruction of justice and impeachable offenses, on the policy front — what is his worst policy that you believe people like?

Moulton: His worst policy that people like? I mean, that’s really a polling question and I’m not a pollster, but certainly anecdotally I hear people say, “You know, putting kids in cages is terribly immoral and he shouldn’t be doing that, but at least he’s dealing with immigration.” And we, you know, Democrats are right to say that we have a humanitarian crisis at the border, but we also just have a crisis, period, because we do not know how to handle bigger numbers, larger numbers of migrants coming from Central America than ever before. And you know, on Day One, as president, I would stop putting kids in cages, but I would also probably quadruple or quintuple the number of asylum judges that we have, so these cases can be adjudicated quickly and either people can go right into our system and get on the tax rolls and get jobs and start contributing to America like the rest of us, or they can go back. But they’re not going to be held in limbo, because justice delayed is justice denied. I would in fact agree to ...

Scott Martelle, editorial writer: Have you introduced legislation that would expand the immigration courts?

Moulton: I have not introduced legislation to do so. No.

Martelle: Why not?

Moulton: Because if you know anything about being a congressman, you don’t literally introduce legislation on every single imaginable piece of thing. I don’t sit on the committee. That’s not something that’s handled by the Armed Services Committee or the Budget Committee. But the second thing is, we do need to strengthen border security, but we need to do it where it matters. That is something, that carrot-and-stick approach, that we need to strengthen ports of entry. There are more drugs coming through the southern border. I mean, we don’t like to admit this in the Democratic Party, but there are more drugs coming through the southern border than anywhere else coming into the country. That’s something that we need to address. We need to have a pathway to citizenship. Of course that should be part of the deal. But the point is that we need to deal with this, and maybe most importantly we need to recognize that as a national security issue, we should be investing. We should be taking that sort of Plan Colombia model and putting it into Central America to address this migrant crisis at its roots.

Garza: When you say you’re —

Moulton: So that was a long answer to your question about —

Garza: You would stop putting kids in cages. What do you mean? How would you deal with families and kids who come to the United States and the border looking for asylum specifically?

Moulton: So I will answer this by using as an example a controversial vote that I took a week or two ago in Congress, which was to vote against an amendment that would have prevented any military funds from being used to house migrant families. And this was a popular amendment because it plays into the whole narrative that we’re doing concentration camps or whatever. But if you actually take the time to look at the way the [Department of Defense] has handled migrants compared to [Department of Homeland Security], which of course is part of our government, the agency that’s putting kids in cages, you realize that DOD does a better job. So I got wrath from the left for taking that vote because it was against Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s amendment. But my chief of staff, who came from DOD, has seen the presentations. I’ve been to the southern border, and I realize that this would actually be an improvement. So it’s an example of where we can do things as a government, even if it means it’s not ideal, using some space on American military bases in the southwestern part of our country to house these families, to deal with this incredible surge of people without putting them into completely inhumane, unsanitary conditions in which they’re currently living. But that’s the kind of thing that I would just do immediately through executive action. I wouldn’t wait to change a law to decriminalize border crossings or something like that. I would just on Day One say, “We’re not going to be inhumane in how we treat these people.”

Garza: So you would still detain them, but you would detain them together as families?

Moulton: Well, one of the things that works pretty well actually is the bracelet system and whatnot. I don’t think that they need to be detained forever, but when they initially come in and get processed, they absolutely should be kept together as families. Yeah. Absolutely.

Mike McGough, editorial writer: Do you have a sense that, as Trump likes to argue, that most or many of the people who are coming across the border probably don’t qualify for asylum? And if that’s true, is the idea of increasing the immigration judges partly a deterrent measure, that people see that large numbers of people are getting a quick hearing, but the result of that quick hearing is that they’re not getting asylum?

Moulton: I simply don’t know the statistics on this, but from spending some time at the border — and by the way, the last time I went to the border, I didn’t go for five hours in a press conference. I spent two days down there on both sides of the border. I’ve been one of the only members of Congress who spent a lot of time in Juárez, Mexico, as opposed to just on our side to really try to understand this. And anecdotally, from all the folks I talked to, and I talked to a lot of people coming here both legally and illegally, my sense is that most of their cases seem pretty legitimate. They’re fleeing for their lives. They’re not just coming to take our jobs, as the president likes to say. They’re coming because their countries are so violent.

So, sure, you’re right. It could be a deterrent if that’s the way the cases pan out, but the most important thing is there’s no reason to say, “Come here, and five years later we’ll figure this out.” Let’s figure it out right away. And that’s a not terribly complicated thing that we could do to start addressing this crisis right now.

But I want to get back to the core of the question you’re asking, which is, “OK, well, how do we deal with Trump? How do take him on?” I said that we can’t just be on this moral crusade to try to convince everybody in America that he’s a bad person, because I just don’t think that’s going to work. I do think we need to talk about how he hasn’t lived up to his promises.

I think we do need to say, “Look, on immigration, the Republican Party controlled the White House and both sides of Congress, and he didn’t do anything.” I don’t think we’re making that message clear enough. He promised the best of a tax cut for the middle class, but most of his tax cut has gone to the wealthy and corporations, and the middle class part expires. He promised the best healthcare system in the world, and his administration is actively working to take healthcare away from people.

I think that is the kind of thing we need to focus on. And importantly, one of the arguments that you don’t hear on the debate stage right now, which is part of the reason, I think, that my voice should be there, is taking him on as commander in chief, and talking about how he is failing to keep our country safe, not just with the Russia thing, but with his erratic policy in North Korea, with his completely erratic handling of the situation in Iran, authorizing air strikes and then 10 minutes later calling them off and sending no clear message whatsoever to the Iranians. How his policy of waving around terrorists is not going to solve the China threat. China’s gonna keep stealing our ideas because that’s how their economy works, and trying to get them to sign some piece of paper that says they’ll stop doing it is not going to be effective.

How will we fundamentally make America safe and strong, I think, has to be part of the conversation, because that’s one of the most important jobs or duties of the commander in chief. So it’s challenging him in these ways that I think we need to take him on to be more successful.

An analogy I was thinking about yesterday — it turns out it’s a very long flight from Boston to L.A., so you have more time to think than I usually get in this job. And I was thinking about the professionalism of the Marines that I served with in Iraq. And we had all the time, as you might imagine, Iraqis who didn’t like us being there and would shout heinous things at us, often in English, so we understood exactly what they were saying.

We’d be in charge of maintaining order of a protest or something. Some people would sometimes throw rocks, and many of these people were terrorist sympathizers and represented the opposite of every democratic principle we presented. But we didn’t stand there shouting back and trying to convince them that they were terrible people. We were just very professional. And if one of them brandished a gun and tried to kill us, we would kill that person. And that’s the kind of professionalism that the Democratic Party should be using to handle Trump. But we’re not doing either. We’re pulling our hair out at all the things he does. And then when it comes to pulling the trigger on impeachment, which I think is just our basic constitutional duty, just what the law says — the president of United States breaks the law, you hold impeachment hearings — we’re not willing to do that either.

I think a lot of people look at us as a pretty feckless party right now, and that’s not the kind of organization you want to want to join. “No better friend, no worse enemy” inspires more people to join you. We’re doing the opposite.

Goldberg: You don’t think that the impeachment process would just increase the disunity that you say you’re trying do away with in the general population?

Moulton: In the general population or —

Goldberg: Don’t you think that the Senate would never agree to it? That it would anger all those Trump supporters?

Moulton: I don’t. I think, first of all, the most important duty is to simply uphold the law. I didn’t swear an oath to the politics of my party. I swore an oath to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States. And, to be honest, I think that that’s enough of an argument right then and there, and I could just leave it there. But you’re asking a political question, and so I’ll give you the political answer. When I first voted for impeachment, and I wrote a vote explanation that said, “The politics are terrible, the timing is bad. I wish we had more evidence. But simply based on the merits, this is the right thing to do to open an inquiry.” That was back in December of 2017. I think the politics were against us. I think it’s shifting. I think that now is the right time to look at the analogy with Nixon. Thirty percent of America thought he should be impeached when they began impeachment proceedings, and when they actually had this debate before the American people and more evidence came out, and people just simply understood what was in the Mueller report, or, in the case of Nixon, understood what actually happened, opinion shifted so dramatically that even the United States Senate, which before it was said, “Oh, the Senate will never convict him,” the United States Senate was obviously willing to convict him, so he resigned.

I can’t give you a brilliant political prediction for exactly where this would be six or eight months from now. But in my humble opinion, and I don’t think I’m a political genius — if I was, I probably would be on that debate stage already, right? My opinion is that public opinion will shift in our direction the same way that my colleagues’ opinion is shifting.

A lot of colleagues have come up to me and said, “Seth, why did you vote for this?” And no one in the party is moving from, “Well, I used to support impeachment, and now I don’t.” Right? Everybody’s moving in the other direction, and I think that’s where the American public would go too.

Goldberg: There seems to be a battle for the soul of the Democratic Party, and you have all these forces pulling to the left. From what I’m hearing you say about immigration, and other subjects, it sounds like you don’t find yourself aligned with the Squad, or with the Bernies and the Elizabeth Warrens who are out there pulling the party to the left. But do you think that that’s a good thing, a good debate for the party to have? Or is it dangerous? Are you worried about how all this leftward pull is going to affect the party in the general election?

Moulton: I think it’s fundamentally a good debate to have. If we want to be the majority party, then we should have to include the majority of ideas, right? That’s a simplistic thing to say, but we can’t be a really narrow party and be a majority, and that means that these are important voices in our party, and I don’t think they should be silenced.

I think the effort of our party leaders should be to bring them into the fold, not push them out. But I do think that the Squad, I’m friends with some of them. I know Ayanna Pressley quite well. I have a lot of respect for their ideas. I do not think they represent the majority of Democrats, and I don’t think they represent the majority of Americans. We just have to recognize that. I don’t think the Twitter-sphere represents the majority of Americans, or even the Democratic Twitter-sphere I don’t think represents the majority of the Democratic Party.

Goldberg: And you’re concerned that they’re going to pull the party too far left in the primary process and the nomination battle?

Moulton: Well, I think that’s definitely a concern. Yes. That could happen. You just saw it literally happening in real time on the first debate stage. I also think that what Trump did with the Squad was morally reprehensible and politically brilliant. Because the history here, it was only a week or two ago, but Pelosi went after them and attacked them, separated them out from the flock, and then Trump saw, he pounced, and of course then the whole Democratic Party had to come to their defense. And the net result has been that the Democratic Party is now identified with them. And that is really good for his reelection prospects.

Garza: Well, you know —

Moulton: Not if he wants to run for a Brooklyn Congressional seat, but if he’s running for president, look —

Garza: One of the cases they make is, look, we’ve tried middle-of-the-road conservative Democratic candidates, Hillary and Joe Biden, and it hasn’t worked. It didn’t work in the last election against a candidate who was just so far to ... well, I don’t know if he’s left or right ... so far outside the political norm that nobody could make heads or tails of it. How can you say with confidence that this is the wrong way to go?

Moulton: Because if you just look at the modern electoral history for the presidency, just take from 1950 onward, it’s been generally more moderate Democrats who have won. John F. Kennedy would be like a moderate Republican by some measures. He has more in common with [Republican] Gov. [Charlie] Baker in Massachusetts than he does with the Democratic Party right now. We tried George McGovern, which I think could very well be an analogy for what we ended up doing this year.

Jon Healey, deputy editor of the editorial pages: Well, Mondale too.

Moulton: And that didn’t work. Jimmy Carter had a lot of appeal. Clinton famously pulled the party more to the center. And don’t forget, Barack Obama, as much as he’s been tarred by the Republicans for being this radical, he was very bipartisan. That’s why there are so many Obama-Trump voters. He very much appealed to the center. And if you certainly look at the most recent evidence we have, which is how did we win the House in the midterms, it was all moderates. Don’t forget people like the Squad who came in, they didn’t flip seats.

Garza: They flipped their primary, yeah.

Moulton: They just won in the primaries. They didn’t help us with the majority one bit. Now, understand, I just say what I believe, and sometimes it gets me in trouble. And I don’t change my position based on political winds. I don’t want you to think that I’m just here saying, “OK, this is the political strategy to run and win,” and it’s not what I believe. This is just who I am. I’m not saying anything here policy-wise that I don’t just believe is right. But I do think that I’m more aligned with most people in America than some of the other folks in this race. And I also think that there are people in this race who are clearly changing their positions to match this movement in the party, and I don’t think that’s going to serve them well.

Garza: For example?

Moulton: I don’t want to throw anyone under the bus, but I think you probably know some of the people.

Greene: You have your colleagues in Congress and counterparts who are running for president who argue that the criminal justice system, the way it’s constructed, is basically racist and that policing in this country is racist, and that both institutions are geared to protect white privilege at the expense of people of color. Is that accurate?

Moulton: I have said very explicitly myself that our criminal justice system is racist in its results. That doesn’t mean that every cop on the beat is a racist, but it’s clearly racist in its results. I’m sure you have 20 anecdotes yourself, but the fact that a Louisiana man, a black man, is sentenced to life in prison for selling $20 worth of weed. I smoked weed in college. I didn’t get caught, but if I had, I’d probably be fined, because I’m a white kid who went to Harvard. I even put it on my application for the Marines, and I didn’t get thrown in prison because I wrote down, “Yes, I smoke weed.” The fact that Paul Manafort gets moved to a nicer prison — this guy committed crimes against the United States of America and is serving a shorter sentence than people who sell pot that’s legal in half the country. It’s completely nuts.

Greene: As president, what do you do about that racism in the system?

Moulton: First of all, abolish the death penalty, because that’s applied disproportionately. We need to legalize marijuana. And not only that, but expunge the records of people who have committed minor marijuana crimes. We need to make it very clear that if you are a rehabilitated felon, then you have the right to vote, and we need to make sure that people who come out of prison are actually rehabilitated. We need to address the opioid crisis by getting people into treatment centers rather than putting them into prison. And I will have a Justice Department that fights relentlessly to make sure that these laws are equally applied and there’s not a separate set of rules for rich people versus poor or white people versus black or anything else in this country. Those are some of the steps that we need to take. But I think your question is specifically about criminal justice reform, but I don’t think you can really address the broader racial disparities in our country without pulling back and looking at other things as well. There’s a lot of racial injustice in our education system that has to end.

A story: I was speaking to a big women’s group that did an event for me in my district back home a year ago or so, a year and a half ago maybe. And I often talk about how even just in my own district, you can live 50 feet from your neighbor but you go to different school systems because you’re on different sides of a town line, and you have different prospects for success in life. This young black woman, high schooler, stood up and said, “You know, Seth, you’re right. And I’ve heard you say that before, but within my ZIP code in my school, in the city of Lynn, white kids get a better education than black kids.” And there are a lot of reasons for that, one of which is they hardly have any black teachers. They don’t have a lot of role models that young people, especially young black men, can identify with. But the point is that there is a lot of racial injustice in our education system, and that’s the system that is supposed to be the great equalizer to ensure equal opportunity for everybody in America. So there’s a much broader racial conversation we have to have.

I think we should have a new voting rights act in America that not only restores the protections of the previous voting rights act, but addresses some of the new ways that people are being disenfranchised. The fact that my Marine buddy, Dan McCready, lost a congressional election in North Carolina, at least in part, because absentee ballots were literally being stolen out of the homes of African American voters — that’s the thing that you’d expect to hear about happening in 1956, not 2018.

Greene: What do you make of Trump’s success of playing up the division and playing on the racial resentment of white Americans? Of some white Americans?

Moulton: Look, the very practical answer to your question is that there is a lot of resentment in our country right now, and I think that it comes most of all from the rapid economic change that we’re going through, and the fact that people are not making what they used to make. Even if they’re not hitting the unemployment statistics, it’s because they have two or three jobs, and they can’t make enough to take care of their family. And Trump has put a racial bogeyman out there, saying that people who don’t look like you are taking your jobs. Unfortunately, it’s something that people have latched onto.

I think, philosophically, that Abraham Lincoln was right. You know, there are a lot of parts of human nature that aren’t great, and it’s up to great leaders to call us to the better angels of our nature. It is the historic practice of demagogues like Trump to call out the worst in human nature. It’s a playbook that we’ve seen. I got in a lot of trouble early on because I compared the rise of Trump to the rise of Hitler. I didn’t say Trump was Hitler, but I said the rise of him in a democratic system is similar to the ways in which Trump is rising to power. I do think there are some frightening parallels that, in the light of history, we need to be very careful of.

When I was in college I was writing a paper on, essentially, what would Kennedy have done in Vietnam. I went to the Kennedy Library, and you get to do all this primary source research, which, you know, I figured out as a student, professors love that. It’s a good way to get an A. I’m pulling all these drawers of files from the Vietnam papers of the Kennedy administration. Then I saw on this list, this drawer that was the contents of the president’s desk, like, on the day that he died. And it didn’t have anything to do with my research, so I didn’t think they’d give me it, but they did, they gave me this, and it was fascinating.

What I’ll never forget is this little piece of paper that Evelyn Lincoln, his secretary, had typed up and sat in his desk, and it said, “The president’s favorite quote.” And Kennedy’s favorite quote was from a great conservative, Edmund Burke, who said, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” I think that that really speaks to the responsibility of leadership and that we need moral leaders in our country, in our Congress, in the White House. That’s why John Adams, you know, gave that first blessing on the first dinner in the White House, that may only good men — obviously he left out women — but may only good men live in this house. It was subsequently inscribed above the mantle or something in the White House. I’ve never seen it. But I think that there is a real moral calling to good leadership. And it’s not simply good enough to not show up, you know, because sometimes it’s, as that quote says, the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. Not for good men to become evil or promote evil, but just to do nothing. If nothing else, that’s why I’m here, I’m running and I decided to get back into this fray of government service even after I’d done my time.

Goldberg: I’m changing the subject slightly. I haven’t heard you mentioned climate change. Where does climate change fall in your ranking of important issues and how would you begin to address that?

Moulton: I think it’s incredibly important. I think it’s an existential threat to the world. I think it’s a national security threat to America. I think it’s an economic threat to America. I am not one to say that it’s more of an imminent threat than Russia attacking us with nuclear weapons, but in the long term it’s a massive threat to the future of humanity, the ability of my daughter to grow up in a world that she can live in.

I think that this is another place where the Democratic Party is starting to go astray a little bit. I was one of the first people to sign onto the Green New Deal, and I signed on so early that it was just an open framework. But then when some of the proponents of the deal or some of the sponsors of it started adding things like a jobs guarantee, a bunch of socialist programs, I think that’s a huge mistake because I think it’s gonna result in the baby being thrown out with the bathwater because it’s not addressing climate change specifically.

I also think they’re fundamentally missing the boat by thinking that addressing climate change is just going to be a necessary budgetary hit to the United States, a big debt that we have to take on, when we can really address climate change by growing our economy because addressing climate change is going to require a lot of new technologies.

We’re going to have to develop new technologies so that the developed world can have carbon regenerating capacity and better electrical grids, but we also need to extend that to the developing world because critics of the Paris Accord are right in that it doesn’t do enough to address carbon coming from the developing world. That’s another thing that can be addressed through technology and distributed generating solutions. We also need to bite the bullet of taking on carbon capture because even if we were to stop polluting today and all those cars were to go home, there’s already too much carbon in the atmosphere. So those, very broadly speaking — United States be a leader for the developed world, develop technologies for the developing world and develop technologies to literally take carbon out of the atmosphere — those are the big, like, high-level things that we should be doing, but we should be doing it by developing the technologies and selling it to the rest of the world. It’s not good for the U.S. economy or for our national security that every solar panel installed in L.A. today is probably made in China.

Garza: Well, this is not going to happen without serious government coercion and intervention, otherwise it would have. How would you put the thumb on the scale? How would you nudge or incentivize the growth of the industry in renewables and other green technology?

Moulton: Well, I think we need to have a carbon tax. Cap and trade is not generally as favored by economists as a carbon tax, although there are ways to do it that are essentially about the same, and cap and trade is actually more palatable. I actually have discussed this with none other than your former governor, Gov. [Arnold] Schwarzenegger who —

Garza: Oh, very former —

Moulton: Very former. Who basically said that, you know, cap and trade is something that the business community can accept, and there are economists who think you can get close to there. I’ve signed onto the carbon tax dividend program so that it basically goes back into the system. It’s a revenue-neutral thing. I also believe that we need to invest in basic scientific research here. I mean, this is a place where it’s important to remember that in the mid-1950s when the Soviet Union put Sputnik up there, we didn’t respond by just simply increasing our defense budget, which is undoubtedly how the Republican Party would respond today. We responded by putting much more money into basic scientific research and graduate school education. Those were the kinds of investments that I think we need to make this in this crisis.

I guess I betrayed my undergraduate degree in physics here, but I think I’m the only candidate who has talked about fusion power. I talk about fusion power not just because it’s a brilliant solution to the carbon energy problem, but because I think that we’re actually — you know, I visit MIT and I keep in touch with these folks, and I think we’re actually closer to getting to fusion power than many Americans think. It’s a big competitive issue if China develops it first and they’re selling that technology to the rest of the world and even to us, than if we’re the ones that win that race.

Garza: Would you favor, then, growing our nuclear energy capability? Because the country has sort of been going the other direction.

Moulton: Yes, I do. That’s a place where I recognize I disagree with some of the people on the left, but it is the biggest source of carbon-free energy we have today. The new technologies for building just existing fission powered reactors, as opposed to getting to the next generation or a couple of generations ahead of fusion power reactors, eliminate the risks that we saw come to the fore with Fukushima and whatnot. Nuclear power has been turned into this very frightening bogeyman, right?

Garza: Well, it’s done some pretty frightening things in Fukushima and Chernobyl.

Moulton: Chernobyl, I mean — if you look at the history of Chernobyl, like it’s impossible to imagine that happening in America. I mean everything possible went wrong. At Fukushima, no one died. Fukushima was the worst modern nuclear accident that we’ve had —

Garza: Not yet anyway. Radiation can build up in your system. Anyway —

Moulton: No no no, they’re very [confident]. You talk to people who’ve done the studies and everything, nobody has died, and no one is expected to have a shorter lifespan because of Fukushima. Every single day, thousands of Americans die premature deaths because of carbon-producing energy sources. Every single day. If you act from a scientific perspective — but you know, if we’re going to be the party of facts, as we’d like to say over the Republicans, this a very, very clear choice here.

Healey: Back to your point about moral leadership. A lot of people on the healthcare front frame single-payer and universal access as a moral issue. Can you talk a little bit about where you would go on healthcare? Do you think it is a right? Do you think there should be universal access?

Moulton: Absolutely it’s a right. I actually said that earlier when we were just talking about taking care of migrants who were dying of heat exhaustion in the desert. I mean, healthcare is a human right and the fact that not everybody in America has access to healthcare is wrong. I got in an argument recently with a Republican colleague because I just asked him, you know, “Do you think that it’s right that Donald Trump’s kids have access to better healthcare than some of the Marines I served with?” Kids who put their lives on the line over multiple tours in Iraq have worse healthcare than Donald Trump’s kids, who did nothing. They just happen to be the kids of a rich guy. This Republican thought about it for a second and I think recognized the political implications of his answer and said, “Yeah, if they could buy it, then they should get better healthcare.” I think that is wrong. I think that that’s morally wrong.

Frankly, I don’t think I disagree with really anyone in my party on this. I think everybody in America, excuse me, everybody in the Democratic Party believes that healthcare is a human right and everybody deserves it. We do have different views on how to get there, and I’m with President Obama. I think that having a public option that competes against private options — and by the way, I don’t think that public option should be Medicare. Medicare was designed in 1963 and it can’t negotiate prescription drug prices; I mean, we can do better than Medicare — but having a public option that competes against private options is a better way to get there to where we want to go.

I say that from the experience of going to the VA and I’ve seen the good, the bad and the ugly of going to the VA. The good is that the VA negotiates prescription drug prices. When I get a prescription from the VA, it’s cheaper than folks who get it through Medicare. The bad is that shortly after I got to Washington, I had to have minor abdominal surgery. I mean, to be fair, I actually thought it was pretty major at the time. Then my wife got a C-section and I was like, “Oh, well, that was no big deal,” but I had the surgery and a great surgeon who didn’t need to be at the VA but volunteered her time because she was at George Washington, whatever, and wanted to take care of vets. She’s putting me under anesthesia, we’re talking about the system, and she’s like, “Yeah, I don’t really trust half the people who are working here.” At which point I was like, “Whoa,” you know, but it’s too late. I was out and I woke up a few hours later —

Garza: Are you sure you heard that?

[Laughs]

Moulton: My cousin came to pick me up to take me back to Capitol Hill, and they prescribed me a pretty heavy painkiller. And they said, you know, when the anesthesia wears off, you’re probably going to need to take two pills. You can try just taking one. I didn’t take any right away because we had votes that afternoon and I wanted to remember how I voted. Then it really started to hurt and I tried to take one pill, didn’t seem to make a difference. I went back to take a second, I look more carefully at the bottle and they’d sent me home with Advil. They literally sent me home with the wrong prescription, and thank God it was not a more dangerous or more addictive medication to what I was prescribed. It was the opposite direction. It made for a painful afternoon, but I was OK.

Healey: You could be OK taking four Advil.

Moulton: I could take a lot of those, yeah. But they even had figured out — when I went into the VA that time, I didn’t say I was a member of Congress or anything like that, cause that’s not the whole point of why I’m going there. They had figured it out. They even knew I was a member of Congress and they were like giving me extra special attention, and still sent me home with the wrong meds.

Healey: Maybe that’s why they tried to kill you.

Moulton: Well, that also could be true, but —

Garza: They were pretty inept at that, too.

Moulton: Then we’ve heard the stories of veterans, you know, dying on waiting lists or not getting the meds. I mean, I have a really good friend I served with from around here who, I’m not sure which VA he called specifically, but he called the VA a couple months ago because for the first time since getting back — and he’s done really well, he’s really successful, has a great kid, and all this — but for the first time he said, “I had a really, really bad week and I felt like killing myself.” He called the VA. It took him 48 hours to actually get in touch with someone to talk to. When he finally did, they offered him an appointment in three months and he said, “I’m not thinking of killing myself in three months. I thinking of killing myself tonight, you know? I need to see someone.”

Garza: That doesn’t sound like a great model for a single-payer —

Moulton: Exactly. That’s my point. The VA’s probably — the critics will say, “Oh Seth, it’s not exactly a single-payer system like Medicare for all,” but it’s probably the closest analogy we have, and that’s not the system that I want to force on everybody in America.

I think competition would help the system. You know, there’s no competition for me going through VA. There’s no healthcare plan that’s competing for my business. The VA is not trying to attract people. There’s no incentive for the VA to have more patients. In fact, it’s a disincentive really.

I think that, you know, the closest analogy I can think of is if I came in as the next president and the first thing I did was I said, “You know what? We’re getting rid of FedEx and UPS because we don’t need competition in the package delivery market.” I mean, does anyone think that that would actually improve the service of the United States Postal Service? I mean, come on. And if you have competition and options for delivering packages, I think you should have it for something much more important like delivering healthcare.

But I acknowledge that, you know, this is a divide in the party. It’s something there’s a healthy debate on. I also think, most importantly, we have to have the debate on policy, but from a political perspective, no one up there is acknowledging the fact that even if you like Medicare for all, you’re not going to get it through Congress. There aren’t even enough Democrats in the Democratic-controlled House to vote for it right now, let alone the Senate. It’s a place where I think, again, the party is really, you know, doing everything we can to shoot ourselves in the foot by promising things that we can’t deliver. That will come back to haunt us.

Healey: This is true across the country, but in California, one of the main gaps in coverage is people north of 400% of the [federal poverty level], some 600% of FPL. The people who are, you know, in the —

Moulton: Where are the numbers around that?

Healey: That’s around $60,000 for a family of three or four to [$80,000] or $90,000 in California. It’ll vary across states. [Editor’s note: It’s $85,320 for a family of three and $103,000 for a family of four in California and the rest of the continental United States.]

Moulton: Right.

Healey: It’s people that we used to think of as middle class, maybe lower middle class, upper working class, who simply can’t afford to pay 15% of their income on premiums, going on 20%. How do you address that part of the affordability issue?

Moulton: Well, what works well in Massachusetts is — because we had Romneycare before Obamacare, it’s a very healthy market. And there are a lot of options, and that has generally brought down prices more than in other parts of the country.

Healey: There’s an individual mandate there too, right? You have to buy insurance in Massachusetts. Don’t you?

Moulton: Well, that was the case under under Romneycare, but essentially Obamacare supplanted Romneycare and, kind of, put it out of businesses.

Healey: The mandate is gone too?

Moulton: The state mandate is gone. Although, I still have to fill out that form on my taxes. I mean, basically Obamacare superseded it. The irony is that in Democratic Massachusetts, Romneycare was much more popular than Obamacare. It actually was a system that was working pretty well. One of the reasons for that, by the way, is because the Massachusetts state Legislature every year improved the program. The system passed in 2006 was not perfect, as Obamacare today is not perfect. What we see at the federal level is everyone’s just trying to tear it apart, or on the Democratic side of the aisle, people are like, “Oh, no, don’t touch it.” Whereas in that, Massachusetts, they were willing to open it up and make changes and tweaks. By the time we got to 2010, 2012, it was a pretty decent system. In fact, entrepreneurs in Massachusetts cited it as the No. 1 or 2 reasons for locating in the state.

Healey: So do you solve the affordability problems in ACA by getting the pools bigger? By getting more healthy people in the pools?

Moulton: Well, that helps. But also getting more competition into the market. One of the reasons why — I have to confess, I don’t know the intricate details of the California ACA market, but I do know in a lot of states with very high premiums people only have one option. You know, there’s very little competition, for example, in Kentucky. There’s basically one option on the exchange, that’s it.

Goldberg: Since you were talking about health and, specifically, your health, I saw that you said you suffered from PTSD. So what does that mean? What kind of symptoms did you have and what did you do about it and how did that affect your life?

Moulton: So when I got back from Iraq, I sometimes would have bad dreams, sometimes wake up in cold sweats. And I had this amazing opportunity: I was going to Harvard business school on the GI bill. And yet I’d sometimes find myself sitting in that classroom just feeling like my life is so meaningless compared to what I had been doing. Even in a war I disagreed with, to impact the lives of other people, and I just sort of felt withdrawn. But to be honest I did not recognize those as symptoms of post traumatic stress, because I knew fellow veterans who were afraid to drive down the highway because they were afraid a bomb might blow up, or were contemplating suicide and were not even able to sit in the classroom at all. So it took me awhile to come to the terms with the fact that I was lucky to not have those more serious symptoms, that I had post traumatic stress at all. And by the way, it’s a bit of semantics, but I call it post traumatic stress because one friend of mine who I served with said, “You know Seth, after what we saw, it would be a disorder if you weren’t disturbed by it.” This is really just a common human reaction to traumatic experiences.

Garza: What years were you there?

Moulton: I was there from 2003 — I did four deployments, so I was there 2003, 2004, 2005 and then 2007-2008. And I was always on the ground in combat situations. And, look, I didn’t have the political courage to disclose it, because I thought it would hurt my career. But I decided that, as someone who advocated for mental healthcare and who’s especially talked about mental healthcare for veterans as a member of Congress, applying for the top leadership position in the country, that I’m kind of being a hypocrite if I don’t lead by example and share my own story. And, look, there’s a part of me that felt like by the end of the week I’d be out of the race, because we’ve seen what’s happened in the past to people who have had mental health issues disclosed.

We also, by the way, know that there are a lot of presidents, successful presidents, that — you know, Lincoln was depressed, Grant was depressed. A lot of people feel that Eisenhower and Bush both had post traumatic stress themselves. But its not something people have been willing to discuss.

Fortunately, my decision to share my own experience has been enormously positive. I guess, I don’t know if it’s hurt me in the polls or not. I’m very far down in the polls right now anyway. But I do know that, anecdotally, we’ve held veteran town halls around the country where people have come up, Vietnam veterans have come up, and shared stories they’ve never shared in 50 years.

I get these messages all the time from people who are not veterans, who just have dealt with mental health issues in their own lives. I had someone, not a close friend, but someone I’ve known for several years now, had no idea he’d been dealing with mental health issues but had lost a son, and he said, “Seth, I’ve been dealing with this for three years, and hearing you tell your story convinced me to finally go see a therapist myself.” So I’m glad I did it. And I also want to acknowledge that there were younger Marines than I that I served with, several in my platoon, who had the courage to share their stories before I did. And that’s one of those things, seeing the impact that — and I shared this with my platoon before sharing publicly — seeing the impact that had just in our smaller groups, just to know, “Oh, jeez, you’re going through that too?” “Yeah, and I went through that and I talked to someone and this is how I found a therapist and.…” And, by the way, many of them are smoking marijuana to help too.

And having that discussion on how to deal with this has been enormously helpful in encouraging others to deal with these problems, too. And in my second platoon, when we were there in 2004 in Najaf, I mean I don’t know hardly anyone who hasn’t at some point since 2004 dealt with a mental health issue.

Greene: And so you began by talking about the failure of leadership you saw while on the ground in Iraq. And so what does that mean? How does that manifest itself, and what do you do about it? Does it mean the United States is too eager to go on military adventures? Or that once it gets there it manages things too poorly?

Moulton: Both. One of my favorite quotes about the Iraq war was from my friend Ambassador Barbara Bodine. If you don’t know her, it’s actually an amazing story, because she was actually in Kuwait when Saddam invaded in the first Gulf War and she was in the State Department in the second one. And she said, “We knew there were 500 ways to do this wrong and one way to do it right. What I didn’t know is we would try all 500 ways.”

The point is we could spend hours going through all the mistakes seen with the Iraq war. But I think you’ve correctly summarized how some people break it down. Was it just a mistake to go in? Was it just a mistake in execution? And I think it was both. We clearly did not ask the tough questions in Congress — not that I was there — about whether we believe this intelligence and whether we should go, and having a good debate about going in in the first place. I remember being on the ground in Kuwait and taking bets with my fellow lieutenants, and I was firmly on the side of, “There’s no way we’re actually going to do this. Bush is not going to do this. We’ll be here for a month as a show of force and we’ll get back on ships, trust me.” And obviously I was wrong.

We also repeatedly screwed up the execution. And one of the anecdotes and one of the decisions, I guess, that sticks in my mind is when Bush chose to fire [Defense Secretary Donald] Rumsfeld. And if you remember, Bush fired Rumsfeld right after the midterms, like the day after. And I said at the time, “You know, he should write a letter to the mother of every 18-year-old who’s died between the time he knew he had to fire Rumsfeld to do the right thing for the war, and when it was politically convenient because of the midterms to do so. And that’s the way a lot of decisions were made in Iraq, with no connection or understanding of what was going on with us on the ground.

Garza: Do you have a plan to get us out of this?

Goldberg: And this is the last question.

Moulton: Yes. So let me start with Afghanistan, since that is the longest war in American history. I think we need to end the war in Afghanistan insofar as it’s a war. But we do need to keep a counter-terror presence there. We can’t make the mistake we made in Iraq, where we withdrew so quickly and so drastically that we then had to go back a year later. And we also need to reinforce the diplomatic presence in Kabul to support the Afghan government. But we need to narrow our scope. We need to recognize where our national interests are and where they’re not. We do have a national interest in preventing another terrorist training camp, that’s a real risk that remains. But we are not clearly willing to make the commitment to turn the whole country into a democracy, and it’s very hard to do.

In Iraq, the security situation is in much better hands. But it’s a place where we need maybe even more diplomatic support for the Iraqi government. Because one of the most frightening things going on in Iraq right now is the problems with their criminal justice system. First of all, they’re just executing a bunch of innocent people. And these prisons have really become terrorist breeding grounds. And that will come back to haunt us if we don’t address it.

But that’s not something you address with American troops. That’s something you address with American diplomacy and American aid. Someone said once that every war America gets into is a failure of American diplomacy. That is true, and we need to make sure we lead with diplomacy in these wars.

In Syria, we need to much more narrowly define our interests, and I think it should be defined as just protecting the people we’ve invested in and trained, and probably carving out a small portion of the southeastern border part of the country and focusing on that. But otherwise, pulling out and engaging in talks in figuring out what happens next with Syria. In every single case, the guiding principle should be that we need to have a clear mission. And that means every private in the army needs to understand why he or she is there and what they need to do to come home. And that’s simply not the case right now.

I will say, when I was in Iraq, we actually did know. With all the problems with the war — you know we had these debates on whether to divide up the country or not or whatever — but we settled on a plan. Ambassador [Ryan] Crocker and Gen. [David] Petraeus really had it figured out. When I took my Marines out on a patrol on some village at night, I understood that this was to secure this village to be part of supporting the government of Iraq, which, if could be made successful, it would allow us to go home.

Ask that question to people of Syria right now. They have no idea what government is coming next. They have no idea what the endgame is. There is no strategy whatsoever. By the way, there’s also clearly no strategy or endgame with our plan with Iran. Because the only thing this administration has said, although it’s obvious not everyone is on the same page, is “regime change.” I mean, imagine if Iran came back to us and said, “OK, here’s the deal: We’ll get back into the nuclear accord if Trump stands down.”

Garza: OK!

[Laughs]

Moulton: [inaudible] but like it’s patently absurd. And we seem to think it’s something the Iranians would accept. It’s ludicrous. It’s ludicrous. What we need to do in Iran is, first, send a really clear message that if you shoot down an American aircraft, drone or otherwise, we will respond. Second, really get our allies together. By the way, I’ve been saying this for awhile, but the administration has actually started to do the second piece of what my three-point Iran plan would be, which is to get our allies more engaged in supporting shipping in the Gulf, not just the United States Navy, to try to rebuild some of these alliances Trump has frayed. And third, most importantly, lay out a clear pathway for them to change their behavior in exchange for releasing sanctions. But not things like regime change, which are completely unrealistic.

But that’s the kind of clear, decisive leadership, moral leadership, that we need from the next commander in chief of the United States. I think these are incredibly important issues for our country, and at the end of the day, although they’re not topping the charts right now, I think they’ll be important issues for voters as well.

Goldberg: Good. Thank you so much for coming in.

Mouton: Thank you for having me. It was nice to talk with you.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.