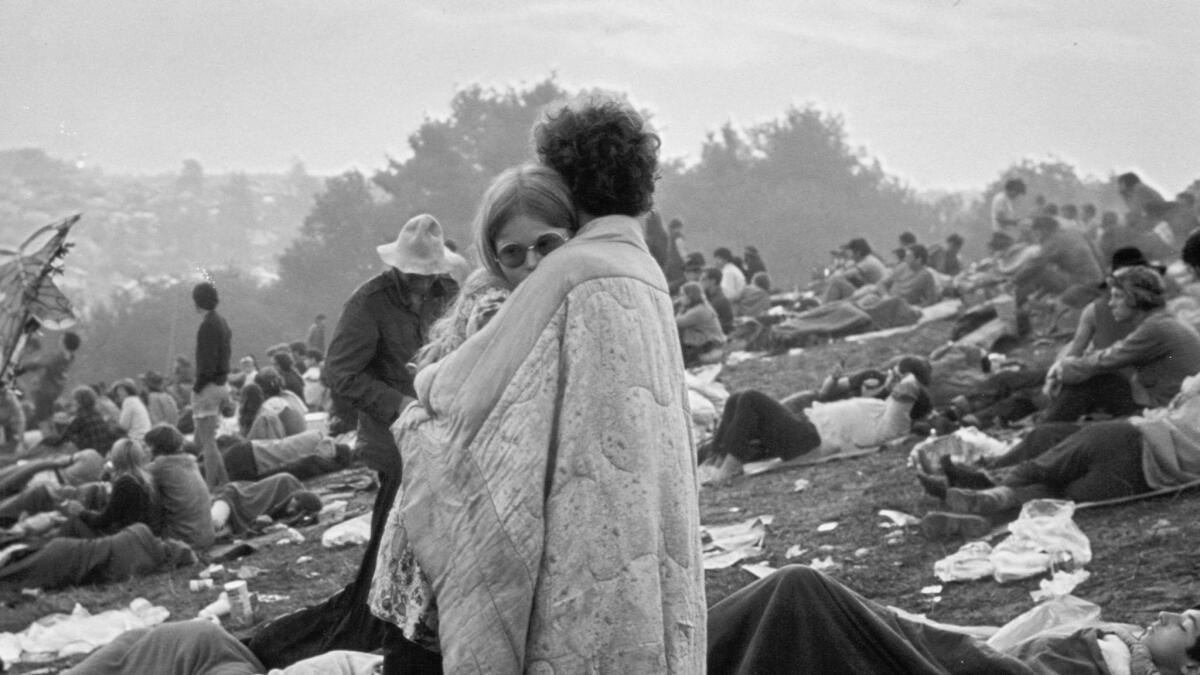

When the Boy Scouts met the hippies at Woodstock

- Share via

They say if you remember the ’60s, you weren’t there. This week lots of people are trying to remember Woodstock, the legendary music festival that took place Aug. 15-18, 50 years ago. I was there, sort of. And my memory is unimpaired: I was a 12-year-old Boy Scout.

Strictly speaking, the festival didn’t take place in Woodstock but on a 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y. — 43 miles from the town of Woodstock. My Scout troop was camping near Bethel that summer.

One afternoon, fed up with atrocious grub at our mess hall, we ventured into town for burgers. Bethel was usually small-town subdued, but this day it was swamped by noisy cars, vans and motorcycles carrying a collection of characters as different from Boy Scouts as could be imagined.

One bearded, exuberantly maned sojourner jerked his head out of a car window and shouted, “Which way to the music?” None of us Scouts knew what he was talking about. The hippie types chose a direction and sped off. They made cultural history. My troop headed back to camp, and learned how to make more knots.

Not til the following spring, when the Woodstock album and movie were released, did I learn how much I’d missed. Yet I noticed certain similarities between the concertgoers and the Boy Scouts.

Both groups followed a back-to-nature philosophy, pursuing a liberating escape from the shortcomings of the big city. Both were intimately acquainted with mud that weekend — the rain that fell inundated the more than 400,000 festival attendees in brown goop, and, though we Scouts were kept dry inside our tents, we were obliged to participate in a “mud trek,” a hike through turbid lake waters, holding our knapsacks above our heads while we got coated in slime. Woodstock featured Jimi Hendrix riffing on “The Star-Spangled Banner”; our troop soulfully sang “Kumbaya.”

If the motto of Woodstock was “peace, love and music,” Scouts were instructed to be “trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean and reverent.” The hippies had an easier mantra to remember, which was probably just as well given their bravura intake of mind-altering pharmaceuticals.

The acolytes of the Woodstock Nation dreamed of a nirvana that would be like an eternal rock concert in which everyone gets along; we Scouts imagined a counter-paradise more like a perpetual camping trip. Hippies smoked pot; we brandished punk sticks — a length of bamboo coated with compressed, combustible sawdust, the fumes from which were perfect for keeping mosquitoes at bay.

The biggest contrast was between headliners. Woodstock’s included Joan Baez, famed for her rendition of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” Our Scoutmaster, Mr. Schlegel, had been a Marine and was as determined a protege of World War II Gen. George S. Patton as a dentist from Queens could be. When he wasn’t drilling teeth, Scoutmaster Schlegel conducted drills with our troop. He never wondered where the flowers had gone, but he was a pro at identifying poison ivy.

Back when the counterculture was in full swing, it was challenging to walk down the street in a Boy Scout uniform. Our crisp khaki uniforms and neckerchiefs stood out against ragged jeans and Day-Glo accented shirts.

“Help any old ladies across the street today?” came the jibes. The more politically active among the hippies despised Scouting as a crypto-imperialist cause.

Change came upon us all; neither the Woodstock Nation nor the Scouts are what they used to be. Attempts to stage a 50th-anniversary tribute to the festival failed, but at least the Boy Scouts now accept girls.

I wouldn’t trade my experience of Woodstock for anything. Peace and love are all well and good, but thanks to Scouting, I still can remember how to tie a slip knot. At least I think I can.

Robert Nason writes about films and books and lives in New York City.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.