Opinion: China’s Communist Party is as shadowy and repressive as when it took power 70 years ago

On Sept. 23, the wife of 38-year-old Chinese activist Wang Meiyu learned that her husband had died in a detention center in Hunan province, less than three months after the police detained him there. Wang had staged lone protests calling for President Xi Jinping to step down and allow democracy in China.

“He was a healthy, normal man when he went in there,” Wang’s widow told Radio Free Asia. “When I saw his [dead] body… he was totally unrecognizable.”

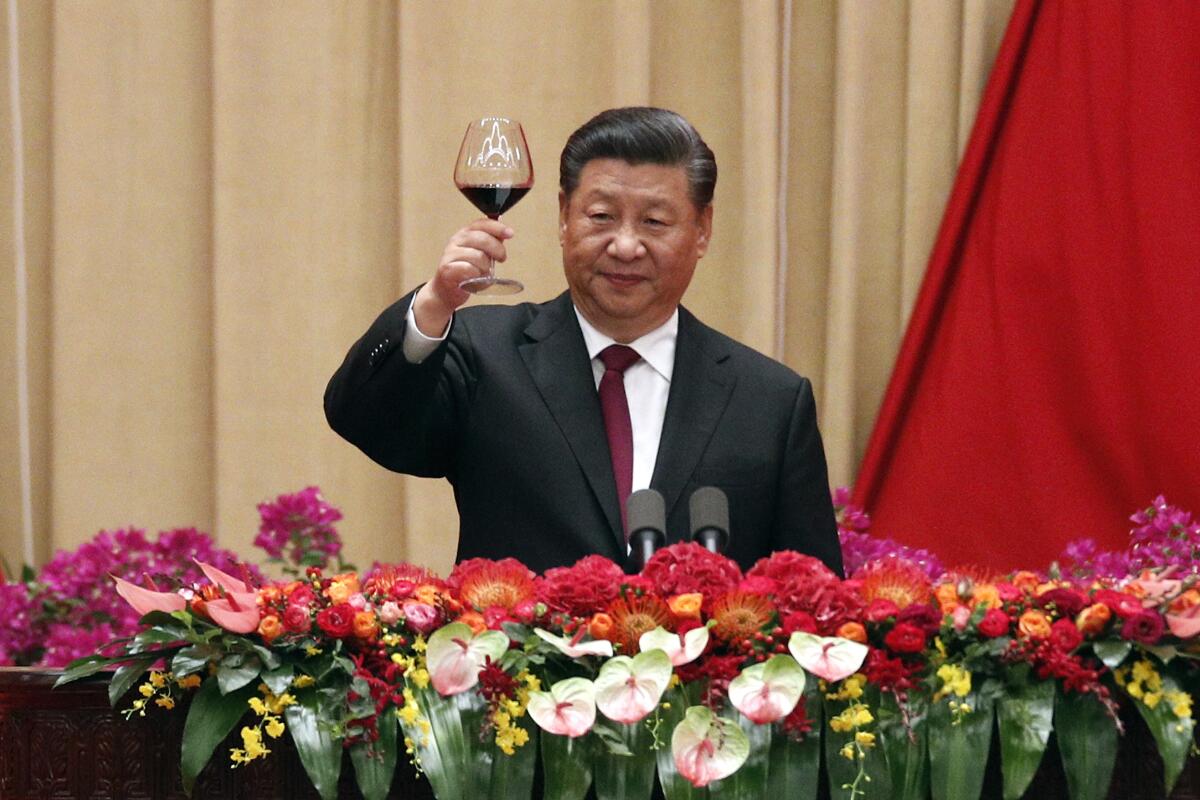

Those who rely on Chinese media for their news are unlikely ever to hear about Wang’s death — or about the hundreds of thousands of other Chinese citizens who have run afoul of the government. Controlling information has always been central to Chinese Communist Party rule, and as the 70th anniversary of that rule approaches on Oct. 1, the propaganda machine is in overdrive. What Chinese people hear are President Xi’s speeches extolling the party’s achievements and interviews with people expressing their national pride. They see images of government-produced high-speed trains, state-of-the-art weaponry, and high-tech mega projects.

“There are actually two Chinas,” Chinese scholar Qian Liqun said in a speech. “One is the China amplified by the historical narrative and propaganda machinery, a China that strides triumphantly and is unstoppable. The other is the China ravaged and denied, perishing in the darkness.”

As a China researcher for Human Rights Watch, I know something about that other China. It’s one where people are routinely imprisoned for speaking out for a more just and free society, where a critical comment online about the president can get someone forcibly disappeared, and where a person can be declared mentally ill and sent to a psychiatric hospital for seeking compensation for expropriated land.

It is the China where a million Turkic Muslims in the Xinjiang region are now being detained solely because of their ethnic identity, while many of their children are forcibly housed in state-run boarding schools. It is the China where millions of women have suffered the trauma of forced sterilizations and abortions, and where children cannot go to school because they were born outside of the One-Child or Two-Child policies.

“The other China” is the one whose existence the Communist Party denies and forbids anyone to speak about.

The other day I came across an anonymous posting by a woman based in Shanghai who had found her way to some Human Rights Watch’s research on Xinjiang — presumably using a virtual private network, or VPN, to circumvent the state censorship that prevents internet users in China from reading uncensored news of the region. She described how her “heart sank” and her “body trembled” as she learned of the government’s brutal repression. She wrote that her daily life in the first China was “good and vacuous,” but when reading censored news websites about “the other China” she feels “uncontrollably frightened” and “powerless.”

Most Chinese people, at least for now, can live their lives untroubled by “the other China.” But there are no guarantees of not being suddenly engulfed by it. The billionaire Xiao Jianhua and the former vice minister of public security and president of Interpol, Meng Hongwei, now live in “the other China,” incarcerated since 2017 and 2018, respectively. Once you are pulled into that shadowy world, it is difficult to get out. Actress Fan Bingbing only reemerged from months of house arrest after making a groveling public apology.

People understand the message of these cases, and do their utmost to protect themselves.

Last year, the writer Yangyang Cheng, tweeted about how, at the age of 8, she learned to be careful about expressing dissent. After a “lively dinner” at her grandmother’s, Cheng said in her tweet, she wrote in her diary about the night’s political discussion. “My mother blocked out the lines with the darkest of ink,” Cheng tweeted, “and told me to never write such things again.”

This is not just the impulse of intellectuals. Even at a time of strong nationalistic sentiment and high tension with the West, many hope to immigrate to Western countries. In 2017, nearly 90% of the applicants on the waiting list for America’s investment-based green cards were from China. Many Chinese have chosen to store their assets abroad—so much so that the massive wave of capital flight in recent years has prompted the party to resort to extreme measures to control it.

After all, no one would want to meet the same fate as Xiao Jianhua or Wang Meiyu.

Seventy years into the Chinese Communist Party’s rule, millions of people now live in the China that promises material comfort and convenience, and projects political unity. But they all live in fear of “the other China”— a reality the party’s top brass relies on to maintain control.

Yaqiu Wang is a China researcher at Human Rights Watch.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.