Column: Presidential candidates love to say they’ll unite the country. Hah

“The purpose of the presidency is not the glorification of the president,” South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg recently declared, “but the unification of the American people.”

Treacle like this has been a mainstay of presidential candidates for decades. But is it true? Or even possible? And if so, is it desirable?

The answer to all three questions is no.

Buttigieg’s description of a president’s job appears nowhere in the Constitution. But more importantly, ideological ambition and national unity cannot be reconciled in the presidency.

Listen to the Democrats running for president. They all say they want to unite the country. But most of them also say they want to implement sweeping federal initiatives and policies, many of which are deeply divisive.

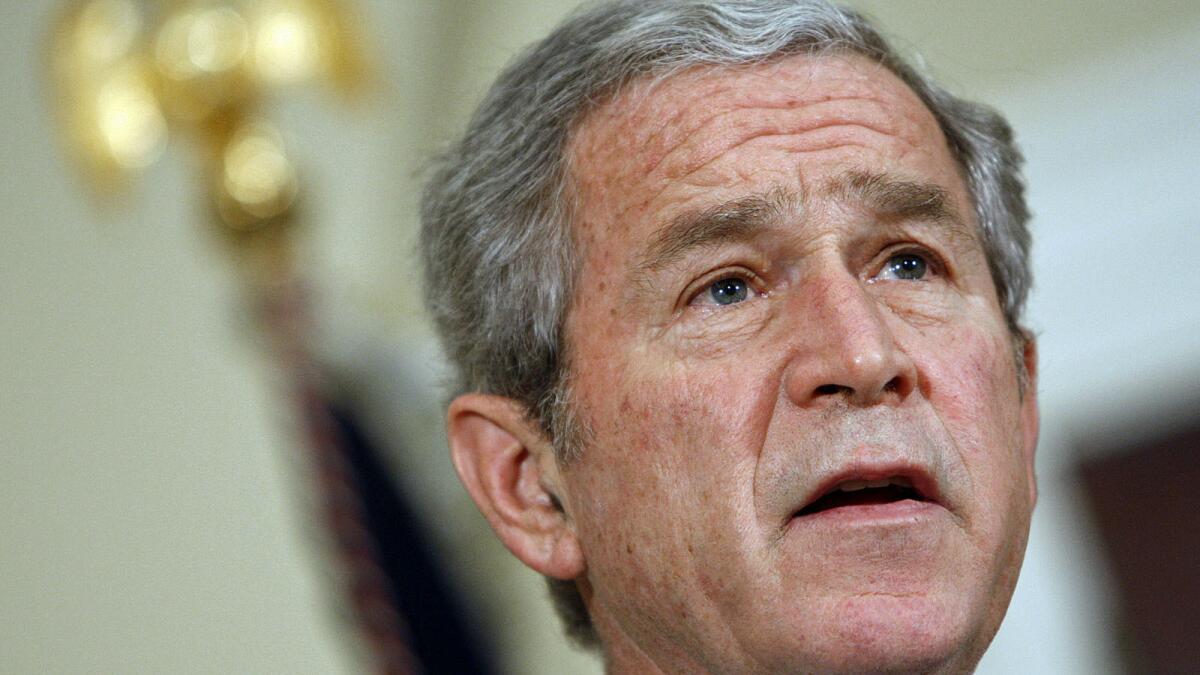

And it’s not just Democrats. George W. Bush campaigned on being a “uniter, not a divider” but won reelection in no small part by opposing same-sex marriage. Upon reelection, Bush pushed for privatizing Social Security. I supported the policy, but it was hardly a unifying cause.

Barack Obama made his name on the national stage while a mere state senator with a brilliant speech at the 2004 Democratic convention. He proclaimed, “There is not a liberal America and a conservative America — there is the United States of America. There is not a black America and a white America and Latino America and Asian America — there’s the United States of America.”

In 2008, he won the presidency on a vow to unify the country. Did he succeed? If he had, we wouldn’t have seen the tea parties or the election of Donald Trump.

Speaking of Trump, he too tried to make the case for national unity. “It is time to remember that old wisdom our soldiers will never forget,” he proclaimed in his inaugural address, “that whether we are black or brown or white, we all bleed the same red blood of patriots, we all enjoy the same glorious freedoms, and we all salute the same great American Flag.”

But here’s the thing: Trump’s florid nationalist touches seemed unifying — to Americans sympathetic to his agenda. But they horrified many Americans opposed to it in equal measure.

That’s the rub. Democrats recognize that the Republican understanding of “national unity” means “winning on our terms,” and vice versa for Democrats.

Right now, on the left and the right, politicians, activists and intellectuals are trying to marry sweeping policy proposals to what Hillary Clinton and her guru at the time Michael Lerner called a “politics of meaning.” On the right such efforts go by many labels, from “nationalism” to “post-liberalism” to the most recent entry, Sen. Marco Rubio’s “common good capitalism.” On the left, which has been at this game longer, the old standbys of “social justice” and “socialism” are most frequently used. But the Green New Deal is certainly another, marrying nostalgia for FDR with crusades against both capitalism and climate change. Both sides have, at various points, tried to flesh out some version of “one nation politics.”

But politics in a republic is almost never about unity. Rather, politics is the art of negotiating differences. Democracy is about disagreement, not agreement. When a politician says that “the time for debate is over” or “let’s put politics aside,” they’re really saying “shut up” to those who disagree.

Americans discard political disagreement for the sake of unity only when confronted with extra-political emergencies. When the country is attacked or when there’s a grave national disaster, the nation rallies around a specific goal. At all other times, a democratic nation is in glorious disagreement about what the government in Washington should do. Factions argue for their desired policies against other factions. The place where most of this fighting is supposed to resolve itself is called “Congress.” Sure, presidents can ask Congress for things. But they don’t get it just because they’re president. That’s the stuff of kings and despots, not a nation of laws.

What are presidents supposed to do amid all the bickering? The answer lies in the job title: They’re supposed to preside over it. The president doesn’t get his or her way; the president gets to either sign off on or veto whatever comes to his desk. After that, the job is to faithfully execute the law.

There’s an epidemic of angry confusion on this point, and it’s making our politics uglier because presidents and partisans try to mask ideological victory in platitudes about political togetherness. When “my” team’s in power, the dissenters are enemies of national unity, which is just a clunky way of saying “unpatriotic.” This is why “dissent is the highest form of patriotism” is an argument that only the losers of the most recent election subscribe to, and why our politics get uglier with every presidential election.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.