Op-Ed: Alexander Hamilton would have led the charge to oust Donald Trump

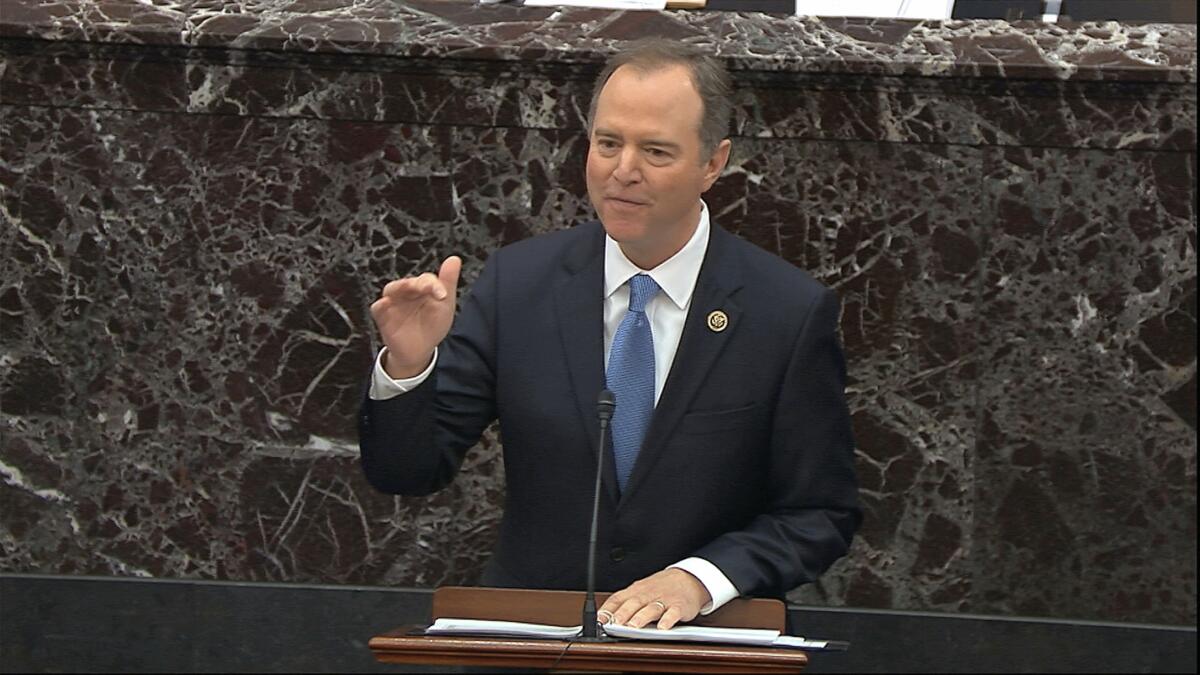

It’s not surprising that Rep. Adam B. Schiff’s opening statement in President Trump’s Senate impeachment trial began with an impassioned warning by Alexander Hamilton about the danger of demagogues subverting the Constitution and pursuing personal gain.

“When a man unprincipled in private life, desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents,” Schiff quoted Hamilton, “having the advantage of military habits — despotic in his ordinary demeanor — known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty — when such a man is seen to mount the hobbyhorse of popularity — to join in the cry of danger to liberty — to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government and bringing it under suspicion — to flatter and fall in with all the nonsense of the zealots of the day — it may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may ‘ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.’”

Schiff (D-Burbank) went on to say that Trump “has acted precisely as Hamilton and his contemporaries had feared” — and that impeachment is one of the core constitutional mechanisms the founders devised to protect our free system of government from such harm.

Now as the Senate sits in judgment of Trump, the members of that body must weigh the prospect of removing him from office — in the face of mounting evidence and testimony — against their own policy preferences.

In this respect, there’s a parallel to Hamilton and the Federalists who were tested by the irregular outcome of the presidential election of 1800. In a critical vote in a single chamber of the Congress, they, too, had to choose between preserving the United States’ constitutional government and supporting a man who might deliver policies they liked better.

Most revealing of Hamilton’s view of the perils of a demagogue in the White House is the stance he took in December 1800 when a fellow New Yorker, Aaron Burr, tied Thomas Jefferson 73-73 in the electoral college vote for the presidency. Hamilton was a Federalist, who advocated for an energetic central government. Jefferson and Burr were Democratic-Republicans, far more concerned with protecting states and citizens from the potential abuses of federal power.

This electoral standoff was unprecedented, driving the selection of the third president into the House of Representatives as laid out in Article II, Section 1, of the Constitution.

Initially, a large group of Federalists in the House wanted to put Burr in the White House, because he was a shaky and capricious adherent to the Democratic-Republican Party compared with Jefferson, who staunchly opposed the Federalist platform of expansive federal powers, broad national taxes, the funded debt, a central bank, and a standing army and navy.

The Federalists in the House, who had it in their power that winter of 1800-1801 to determine the fate of the presidency, considered Jefferson to be their worst nightmare. They deplored his principles and policies on almost every political issue that had emerged since he became secretary of State in 1790. Burr, they felt sure, would bend to their will far more easily, enabling them to advance their party’s agenda in spite of his formal affiliation with the Democratic-Republicans.

Hamilton, an acknowledged leader of the Federalist Party, had a radically different view of the impending vote. Burr, a man he knew well from New York political and legal circles, he said, was “deficient in honesty” and “one of the most unprincipled men in the UStates.”

One example Hamilton gave of Burr’s corrupt intentions in government was Burr’s lobbying in New York on behalf of a land speculating company, the Holland Company, while “a member of our legislature.”

If Burr gained the White House, Hamilton believed, he would “disturb our institutions” and “disgrace our Country abroad.” He would “listen to no monitor but his ambition” and be governed by a singular principle — “to get power by any means and to keep it by all means.”

Consequently, when Hamilton heard reports of the Jefferson-Burr electoral tie, he barraged his fellow Federalists in Washington with more than a dozen letters imploring them to “preserve the Country!”

He told them repeatedly that their party must vote for Jefferson, who, though their political enemy and the champion of policies abhorrent to them, was nevertheless a man devoted to the Constitution.

As Hamilton wrote in one letter: “[If] there be [a man] in the world I ought to hate, it is Jefferson.” But Burr, he said, would drive the country toward chaos and tyranny, “content with nothing short of permanent power in his own hands.”

In a striking echo to the impeachment charges against Trump, Hamilton further noted that if Burr ever reached the White House, there was a risk that, for the purpose of self-benefit, he would undertake “a bargain and sale with some foreign power, or combinations with public agents in projects of gain by means of the public monies.”

The historical consensus is Hamilton’s efforts that winter to avert a Burr presidency proved decisive. In February 1801, the House cast 35 consecutive ballots for president, none of which achieved the nine-state majority necessary to declare a victor. Only on the 36th ballot, thanks to the votes and abstentions of the Federalists, did Jefferson win with a 10-state majority. Three years later, in a battle of honor, Burr killed Hamilton in a duel.

In Trump’s impeachment trial, senators are facing an existential choice similar to what the Federalists confronted in their critical vote: whether to put aside their partisan and short-term policy objectives in the best interests of the nation.

Hamilton’s advice today would be the same as it was in the Jefferson-Burr contest of 1801. “The public good,” Hamilton wrote to another Federalist congressman as he labored to keep Burr out of the White House, “must be paramount to every private consideration.”

Eli Merritt is a visiting scholar in the department of history at Vanderbilt University.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.