Op-Ed: Baseball’s steroid era was bad, but the Astros cheat was organized crime

Baseball has been the background music of my life. Now, thanks to the Houston Astros and their sign-stealing cheat, I’m humming a different tune.

I grew up in a Wisconsin town just big enough to have minor league baseball. The team name was the Indians, and nobody gave that a second thought. They were a Class-D Dodgers farm team; they played in a park a bike ride away, with a roof over the bleachers and walls with vines. One of their stars was a catcher named John Roseboro, and, years later, in the big leagues, he was hit on the head with a bat by the Giants’ Juan Marichal. My hometown hated Marichal. Probably still does. Baseball creates impenetrable loyalty.

When I was barely old enough to drive, I scraped together enough money to take my great-aunt to a Milwaukee Braves game. Yes, Braves, not Brewers. These were the Braves of the National League, of Warren Spahn, Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews, the Braves of the 1957 (won) and ’58 (lost) World Series, both against the Yankees.

Great-Aunt Dora, in her 80s, navigated the stadium stairs and saw her hero, Aaron, get fooled on a down-and-out curveball, flick his wrists and hit it into the right-field bleachers anyway. We talked about it forever after that. She was well into her 90s when she died in a nursing home, within reach of the little radio that brought her every game and every flick of Aaron’s wrists.

College led me to my first newspaper job, which was only a temporary distraction from baseball. I married a woman whose mother had spent long hours sitting in her family’s fishing boat in Wisconsin’s Little Sturgeon Bay, listening to a transistor radio and Earl Gillespie (our Vin Scully) bringing her every pitch of her beloved Braves. My mother-in-law was a star writer at the Sheboygan Press in the town where I grew up. I was 60 miles away at the Journal, in Milwaukee, and she wasn’t happy when I wrote about her beloved baseball team, by then the Brewers of the early 1970s. I wasn’t always gentle. At that point, the lure of tough journalism outweighed any devotion for a home team, or the game itself.

I wrote about Bud Selig’s driving ambition, for instance, to return a major league team to his city. The Braves had left for Atlanta in 1966. The characterization of Selig as too corporate and relentless was always a bit incomplete. He was, first, a fan, like the rest of us. The difference was that, when the Braves left, he did something about it. I sat with him in hotel hallways as major league owners met behind closed doors. I told him about my great-aunt and Aaron’s wrist homer. He waited to collar one or two owners and make his pitch for Milwaukee. Mostly, they just walked past him.

Eventually, Selig got his way and became president of the Milwaukee Brewers. He visited the press box often. He said he was checking on us reporters. Actually, he was hanging out with us. He always smoked a big, ugly, smelly cigar. I amused myself by mentioning it in just about every story I wrote. I referred to it, accurately, as “a big, ugly, smelly cigar.” He feigned anger. One day, it was real. His wife, tired of my cigar reports, ordered him to quit.

A few owners who had walked past him in those hotel lobbies were still around in 1992, when Selig became commissioner of Major League Baseball. He was the boss until 2015 and still retains the title of commissioner emeritus. Now, he must be sitting in his office in Milwaukee, brow wrinkled, and, like me, wondering if the sport we thought we knew so well and loved so completely can retain its mystical wonders, its power as an influencer.

I eventually went to a bigger paper, this one. I wrote about baseball’s trials, steroids, ending an All-Star game in a tie, new playoff formats. I suffered with millions of L.A. fans over Dodger owner Frank McCourt and how to get rid of him. But none of that prepared me for the Houston scandal.

Steroid use is probably more serious but less conspiratorial than what the Astros did. Electronic sign stealing is unsettling, and what wasn’t high tech is disconcerting in its stupidity: garbage-can banging? An assumption that nobody would squeal, even after they went to another team?

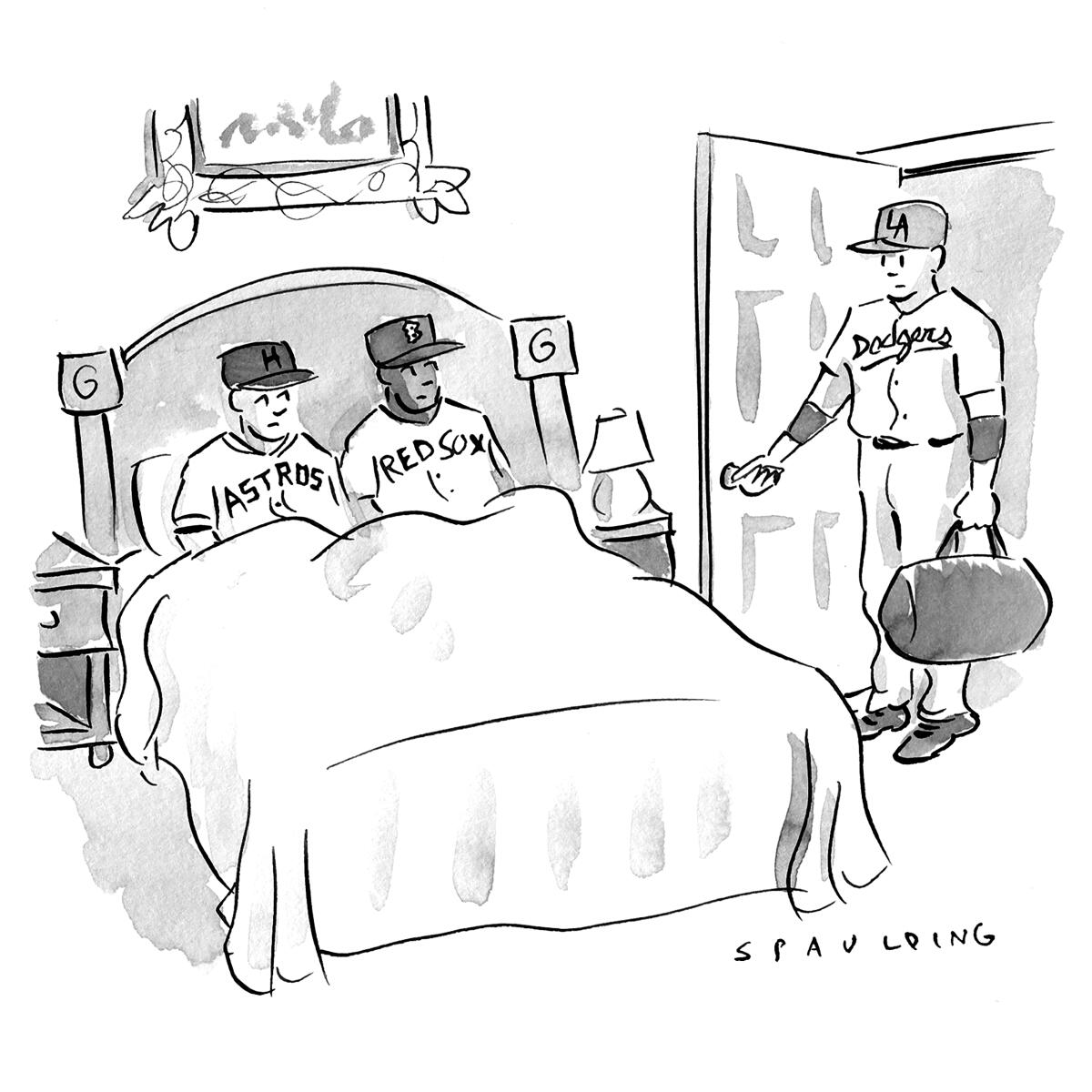

Steroid users were on their own. The Astros were a gang, organized crime. Almost worse: An entire baseball team adopted a philosophy that should be anathema to baseball. They decided seeking any edge was worth it, no matter the moral and ethical damage. The bad behavior may have leaked over to the Red Sox; it may have robbed the Dodgers of a championship.

In my twilight years, as a sports columnist, baseball’s background music kept playing for me. I heard it when I talked to class acts in the game, such as Mike Trout, Clayton Kershaw, Torii Hunter, Howie Kendrick and Mike Scioscia. I thought I was dealing with the same when I spoke, less frequently but often enough, with Astros stars George Springer, Jose Altuve and Alex Bregman.

I apparently was wrong. None of them has fessed up, which for me only accelerates the presumption of guilt. They need not wonder what will appear in the first paragraph of their obits.

The Astros say now they will apologize as a team at spring training (pitchers and catchers arrive in Florida this week). It will be too little, too late.

Now, I will think about the joy of watching Hunter in the clubhouse, a true leader, about the underrated Kendrick becoming a postseason hero. I will think about my grandson, a high school catcher in Maryland who believes that calling the right pitch and blocking balls in the dirt is the best thing in life. And I will think about my great aunt, gone now some 40 years, and how much Aaron’s quick-wrist homer thrilled her.

Maybe then, the music will come back.

Bill Dwyre is a former sports editor of The Times.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.