Opinion: Welcome to the debate stage, Michael Bloomberg. Got some questions for you

Boss-level move, Michael R. Bloomberg.

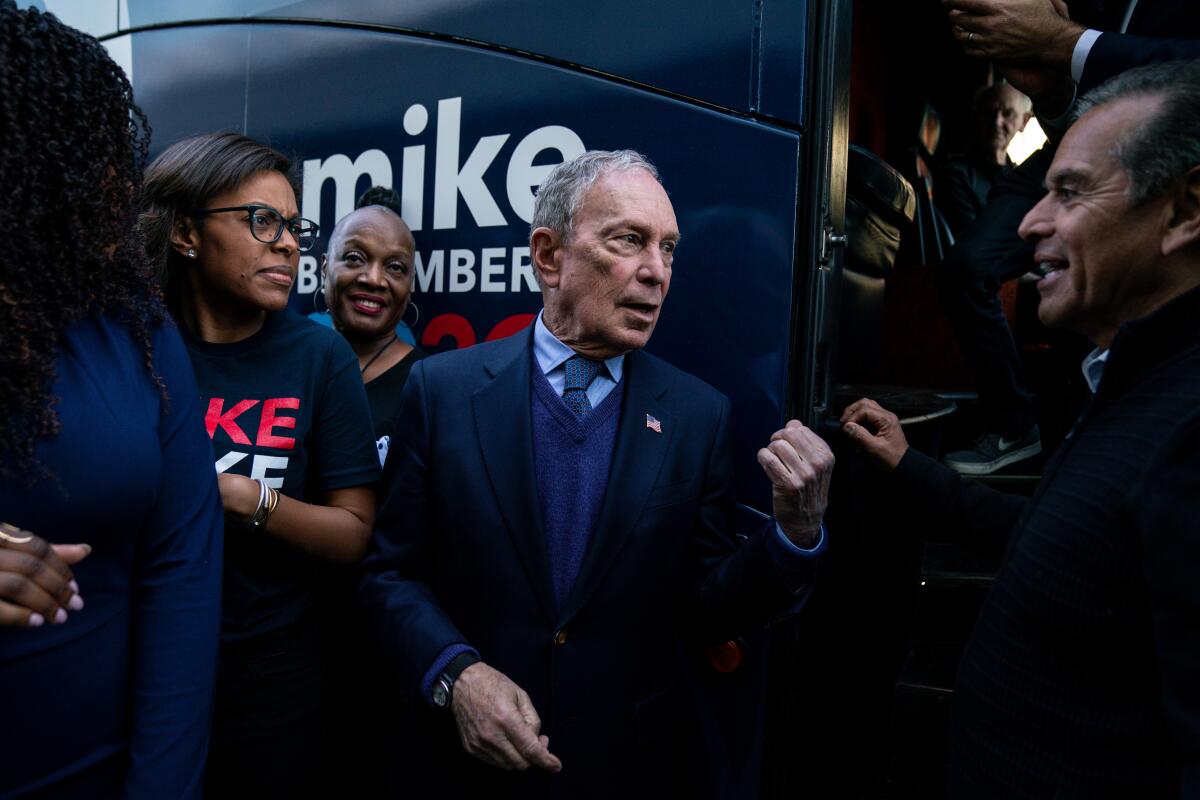

The day before his debut on the Democratic debate stage, the billionaire former mayor of New York City unveiled his plan to shore up numerous rules on Wall Street, banks and lenders that the Trump administration has undermined. Included are a laundry list of proposals championed by progressive Democrats, such as slapping a tax on financial transactions (hello, Bernie Sanders!), reinvigorating the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to crack down on payday lenders, debt collectors and other noxious financial-industry practices (hat tip to Elizabeth Warren!), strengthening the law against redlining by banks (never mind that 2008 speech!), jailing more white-collar criminals and offering low-cost banking services through the U.S. Postal Service. Although it doesn’t propose to go as far as Warren or Sanders would on, say, erasing student-loan debt, it’s specific, cogent and comprehensive.

Billionaire former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg faced attacks by other Democratic presidential candidates on the debate stage in Las Vegas on Wednesday night. Former Vice President Joe Biden, former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, and Sens. Amy Klobuchar, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren also turned their fire on each other. The candidates sparred over healthcare, experience, sexism and transparency.

But it also contains a whiff of the thing that gives me the most qualms about Bloomberg’s governing philosophy. A technocrat rather than an ideologue, he has a reputation for being data-driven and keen on finding and adopting best practices. But he’s applied the levers of government in some novel and intrusive ways, which makes me wonder what the limiting principle is in Bloomberg’s view of government power.

That’s not something likely to get much attention at Wednesday night’s debate in Las Vegas, when Bloomberg joins five of the other candidates vying for the Democratic nomination. (Somewhat fittingly, he will be replacing another billionaire and prodigious campaign spender, Tom Steyer, who did not meet the threshold set by the Democratic National Committee.) The debate’s five moderators — yes, that’s nearly one per candidate — will almost certainly be more interested in confronting him with the questions many Democrats have been asking since he jumped into the race months after it had begun:

Why should voters support your trying to buy your way into the White House?

You’ve apologized for continuing “stop and frisk” as mayor of New York, but doesn’t your previous support for the program disqualify you to be this party’s nominee?

What about all those sexist comments attributed to you and allegations of gender discrimination, or worse, at your media empire?

Can Democrats count on a billionaire to attack income inequality?

Despite his reputation as a moderate, Bloomberg actually has established his progressive bona fides on a number of key issues, including climate change, immigration, gun control and college affordability. His problem, as the flak he’s been drawing from his current party suggests, is that he’s a suspect messenger.

The concerns raised by Bloomberg’s past comments and actions are legitimate, yet Democrats always seem to care more about how their candidates may have transgressed in the past than how well they might serve today. Or even how those transgressions might compare with those of the nominee on the other side.

I’m more interested in what candidates are likely to do if we elect them. Which brings us back to the question that no one is likely to ask Bloomberg: Where does the government’s power to fix things end?

Critics often complain about “stop and frisk” singling out people of color, but that problem stemmed from where and how New York implemented it. There’s a bigger problem in the very conception of the practice. Even if you like the idea of getting guns off the streets and making communities safer — and who doesn’t? — empowering police to pat down whomever they please without requiring some sign of wrongdoing is a chilling assertion of government power. Yes, the Supreme Court has upheld the legality of stop and frisk when police have a reasonable suspicion that a person is armed and dangerous. But the practice is better suited to police states, and besides, the data from New York suggest that putting more cops on the streets did more to reduce crime than stop and frisk did.

Then there’s Bloomberg’s efforts to make New Yorkers healthier, regardless of whether they wanted to be. Some of these initiatives were or became national trends, such as bans on restaurants using artificial trans fats and on smokers lighting up in bars, restaurants, workplaces and parks. Some never quite caught on, such as his push to reduce the amount of salt in food. And at least one — his effort to stop the sale of large sugary drinks — was thrown out by the courts. These steps epitomize the nanny state idea that the government needs to protect you from yourself. Even if that may occasionally be true, granting that sort of responsibility from individuals to the government puts society on a truly slippery slope.

One last and more subtle example comes from Tuesday’s financial regulation plan. Bloomberg wants federal securities regulators to help promote his social equity goals by requiring publicly traded companies to “publish information on the racial and gender composition of their boards, senior executives, hiring, pay and procurement.” He’d also enlist them in his climate change efforts by having them make corporations “report on climate risks,” while imposing a fiduciary duty on Wall Street asset managers to consider such risks.

Granted, Bloomberg’s goals here are worthwhile, even (in the case of climate change) essential. But once he expands the Securities and Exchange Commission’s purview to engage in those battles, what else would he ask it to do?

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.