Op-Ed: There’s a better way to vote: Choose more than one candidate and rank them

- Share via

On Tuesday, it was election day in three states, including Illinois. But you could also have gone to the polls more than two weeks earlier in Illinois, on March 2.

Like the District of Columbia and 37 other states, including Arizona and Florida, Illinois allows its citizens to vote on or before election day, in person or with a mail-in/drop-off ballot. In California, many voters get up to 11 days to vote at the polls and nearly a month to vote by mail. Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon and Washington have all-mail voting systems. The voters in those four states get their ballots two to three weeks before an election, and they can mail them in according to deadlines each state sets, or drop them off at designated places on election day.

These various early voting rules are meant to make it more convenient to cast a ballot. The idea is to increase participation in the democratic process and to decrease long lines at the polls. It’s all good, except when early voting works against its own goals of perfecting democracy: A lot can happen in a race just before election day, so early voting can mean wasted votes.

The crucial Super Tuesday primaries this year were proof of that. All of the voting states but one, Alabama, had some form of early voting that day. Democratic primary voters who cast their ballots as late as the weekend before March 3 would have seen major candidates drop out of the race after they voted. If they chose Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar or Tom Steyer, they essentially voted in vain. Illinois voters who showed up very early on March 2 to vote could have wasted their votes on Klobuchar or Elizabeth Warren.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Ranked-choice voting could have maintained the advantages of early voting, without the downside.

Under a ranked-choice system, first-choice votes for those Super Tuesday primary candidates who dropped out before election day would have gone to voters’ second-choice candidate, then to their third-choice candidate if their second-choice candidate was eliminated, and so on until the votes landed on a candidate who won at least 15% of votes and therefore qualified for a share of Democratic delegates.

If your heart was with Buttigieg but you also preferred Michael R. Bloomberg to the rest of the field, you could have ranked Buttigieg first, Bloomberg second and instead of your vote not counting when Buttigieg dropped out, it would have shored up Bloomberg’s support.

In a general election, where there are usually fewer candidates, ranked choice still fortifies your vote: If your first choice is eliminated because the candidate receives the fewest first-preference votes, the vote goes to the second pick, and so on until only two candidates are left standing. The highest vote-getter of the top-two candidates wins.

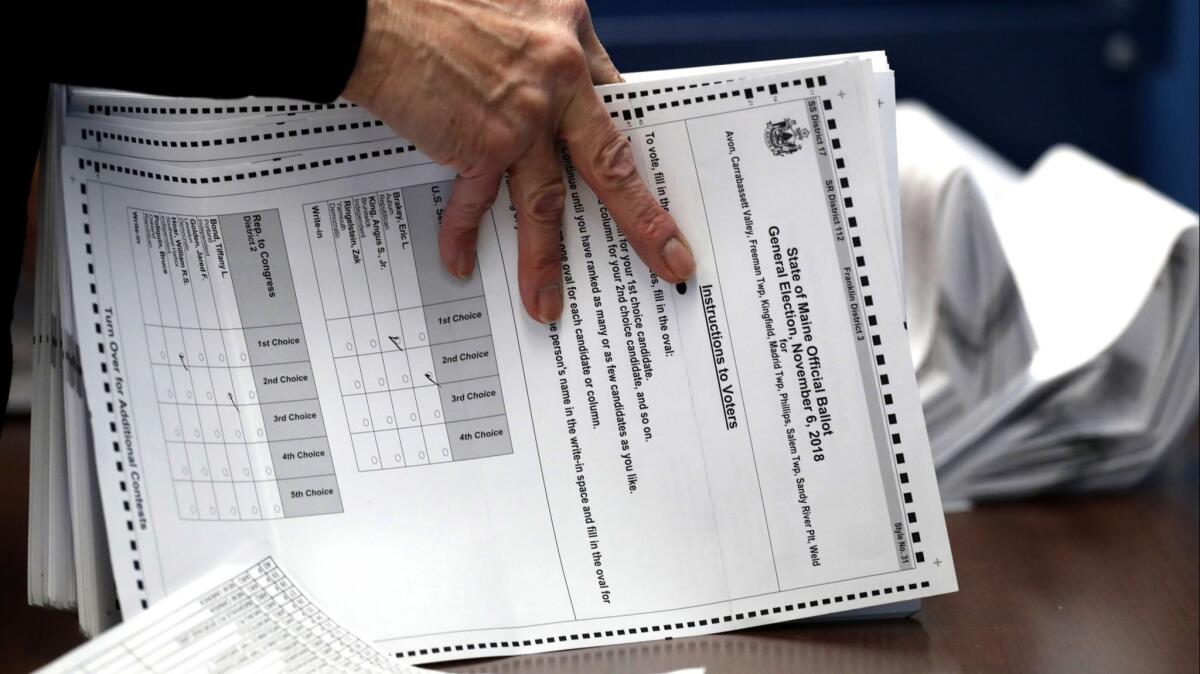

In 2020, five states (Alaska, Nevada, Hawaii, Kansas, Wyoming) are using ranked choice for presidential nominations in major party caucuses or primaries. Currently, Maine is the only state to use ranked choice voting for all state and federal elections with the exception of presidential primaries (it will be implemented for primaries in 2024).

Ranked voting is much more common in municipal elections. Eighteen towns and cities, including Berkeley, Oakland, Minneapolis, San Francisco and St. Louis, have ranked-choice voting. Cambridge, Mass., has used it since 1941. New York will adopt it in all city primary and special elections beginning in 2021.

Ranked choice’s superiority is perhaps most clear in situations like this year’s Super Tuesday, where early voting combines with a big field. But it has other advantages; among them: It can prevent “vote-splitting” in races with multiple candidates from one party. For state and municipal elections, it can replace expensive winnowing caucuses and primaries altogether, saving money and time, but still giving voters the same level of choice. It helps grass-roots candidates; they often lose supporters who fear throwing away votes on a little-known newcomer or outsider. And it encourages civil campaigning because candidates are not only vying for base support but also seeking to appeal to supporters of other candidates who could get eliminated in early tabulations.

We should all want to maximize participation in our democracy. Early voting gets us part of the way there. More states should add ranked choice voting to the effort.

Sean McMorris is the Los Angeles/San Gabriel Valley chapter leader of Represent.Us and an organizing and policy consultant for California Common Cause.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.