Editorial: California schools need leadership. Here’s where to start

By the time Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that most California schools would have to start the fall semester online, the state’s seven biggest school districts, representing 17% of its students, already had announced that they were going online-only or were headed in that direction.

Given the surge in COVID-19 cases, the decision was inevitable. The current situation is treacherous, and too much is unknown about where the pandemic is headed. Yes, other nations have successfully reopened their campuses, but they started with much lower infection rates than the more than 30 counties on California’s watchlist, which includes Los Angeles and Orange counties.

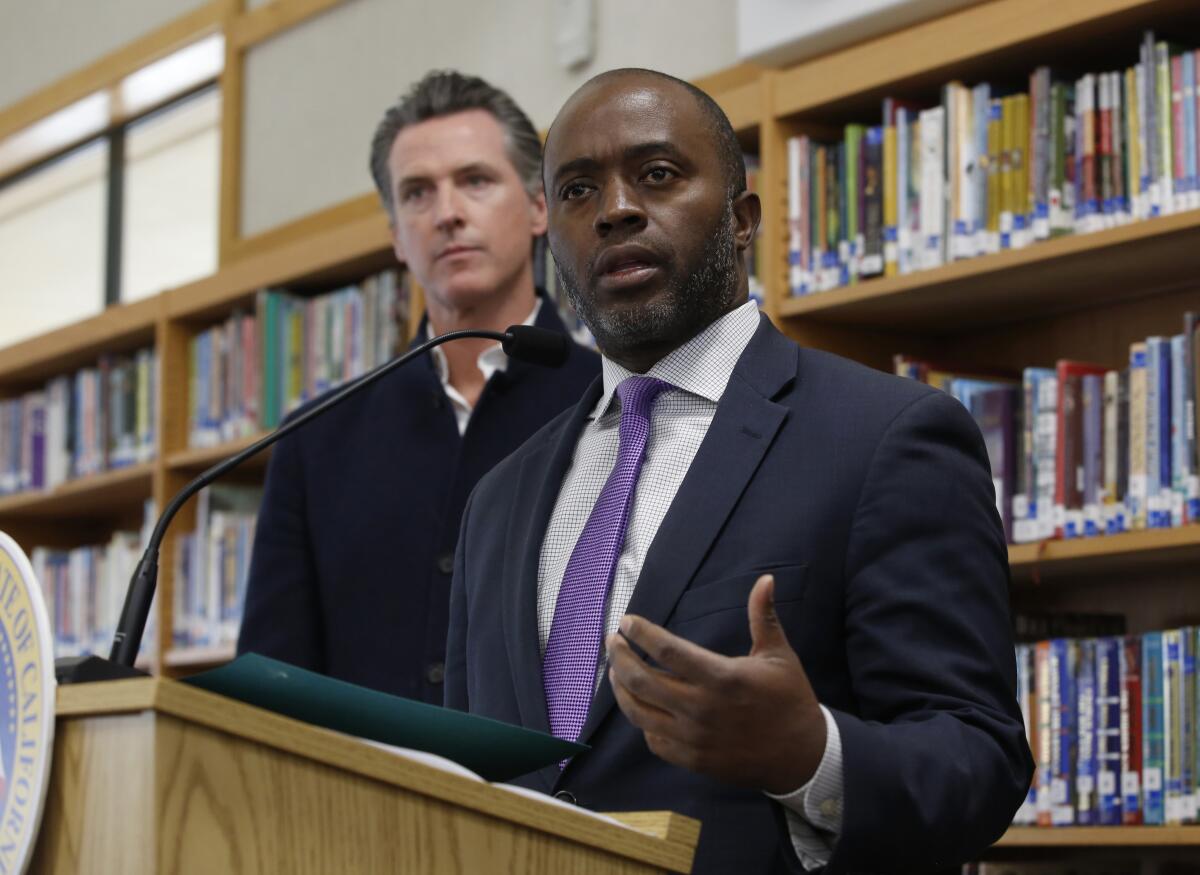

Individual school districts in high-infection areas have struggled to figure out what to do — whether to conduct classes in person, online or a hybrid of the two — and how to design each scenario. Newsom’s order relieves the immediate uncertainty, but once again, the larger school districts (and the powerful California Teachers Assn.) have provided the leadership here. Newsom, the state Board of Education and Tony Thurmond, state superintendent of public instruction, have been followers.

Up to now, the state has largely provided schools with vague guidance and let them go their own way. A few mandates were written into the new state budget to require regular instruction, the taking of attendance and report cards with real A-F grades, but now is the time for strong, specific leadership for schools, with rules that set the standards for the months to come.

Here are some of the steps that state leaders need to take and the uncertainties they need to eliminate to give schools the best chance of succeeding this fall:

- Provide expertise and clear rules on what it takes to reopen safely. Newsom has done this in terms of infection levels needed to close a classroom or an entire school, but schools need more help on how to provide classrooms that are safe for students. How many tables? What configurations? Is plexiglass needed? That’s not to say all schools have to be the same, but they shouldn’t all have to reinvent COVID-19 safety from the ground up. The state should provide assistance in setting up schools and inspect reopened schools at random to ensure they’re operating safely.

- Set clear, firm and rigorous requirements for the amount of instruction by teachers, both live and recorded, when conducting classes remotely. Maximize the safe employment of almost all paid staff, including remote tutoring by qualified aides and support staff and remote or in-person healthcare by nurses; don’t leave this to union negotiations in individual school districts.

- Ensure that before reopening, infection rates are low enough that relatively minor upsurges won’t close them again within weeks. To that end, require masks not just in schools but in the communities surrounding them and ramp up enforcement. Otherwise, schools will yo-yo back and forth between on-campus classes and distance learning.

- Build enough coronavirus testing capacity for schools to test kids and teachers regularly once they reopen, and instruct them how often it needs to happen.

- End the one-size-fits-all approach. In counties as vast as Riverside and San Bernardino, where communities in the mountains or in the desert could have very different COVID rates from more urban or suburban cities, some schools may be able to open earlier.

- Consider the latest science. The newest study from South Korea shows that students ages 10 to 19 are just as likely to spread the coronavirus as older people, but children 9 and younger are much less likely to spread it. The youngest students also are the ones who most need a classroom education to learn the basics, connect with teachers and socialize with others. These factors should be taken into account, rather than shutting or opening all the schools within a district.

- Take the lead in using empty schools to house safe child care and learning centers, equipped with computers and tutors, for families who need them.

State officials shouldn’t be afraid to learn from other leaders’ decisions. Not all states will be as circumspect as California. Schools will probably reopen under all sorts of conditions. That could end up being a tragic mistake — or not. Either way, California schools can and should benefit from the new knowledge.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.