Op-Ed: The Trump administration pushes Bristol Bay closer to disaster

Think elk by the thousands grazing the grasslands in California’s Central Valley before the Gold Rush. Think 60 million buffalo thundering across the Great Plains. Think of the Columbia River when 16 million salmon finned their way upstream to spawn, now reduced to imperiled species.

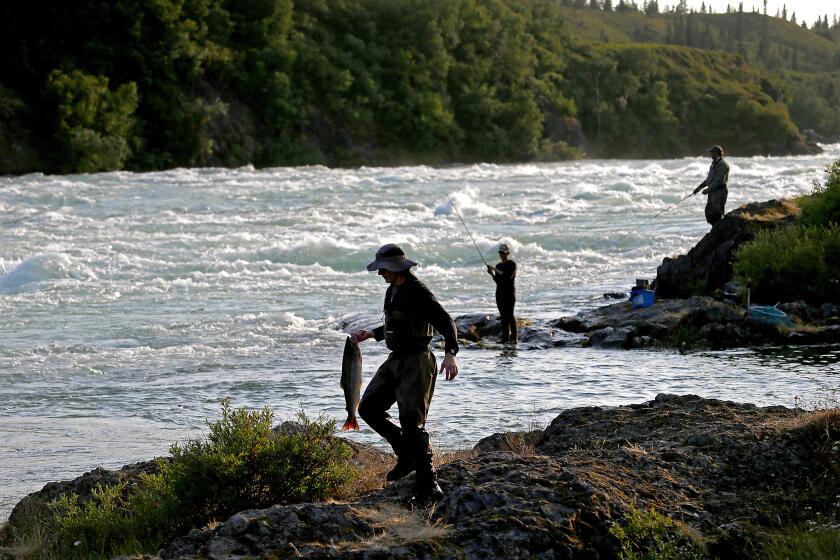

Such visions of unmarred, past abundance provide a clue to the richness remaining at Bristol Bay, Alaska, where not 16 million but as many as 60 million salmon still return from ocean depths to wilderness rivers. The fish nourish orcas, bears, the livelihoods and culture of Alaska’s native people and a commercial fishing industry that delivers 46% of the sockeye salmon marketed worldwide. The fishery generates $1.5 billion in annual income and 14,500 jobs, a gift of the wild waters and mountains of Southwest Alaska that could last forever if we would only let the place be.

But Bristol Bay’s salmon are threatened by a Canadian corporation that proposes to excavate a massive open-pit mine to exploit and export American minerals, primarily copper and gold. Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd.’s Pebble Mine advanced in the permitting process on July 24, when the Army Corps of Engineers released a final environmental impact statement on the project. Contrary to most assessments of Pebble Mine, the Trump administration’s Army Corps concluded that the project would “not be expected to have a measurable effect” on the salmon or the fishing industry. Final approval from Washington awaits; if it happens, it would reverse previous federal decisions based on years of analysis.

Dynasty’s mine — an excavation the size of 460 football fields — would affect hundreds of miles of streams, and its pipeline — 188 miles long with 82 miles of road — would lie squarely between two of our most extraordinary national parks and preserves, Lake Clark and Katmai.

A giant open-pit copper and gold dig above Alaska’s Bristol Bay could yield sales of more than $20 billion in two decades, but Pebble Mine would place the world’s greatest wild salmon run at risk forever.

Each part of this proposal seems worse than the last. Consider the earthen dams, up to six stories high intended to contain runoff from toxic tailings of acids and heavy metals, keeping it from the pristine watershed of Bristol Bay forever. Such containment is at best compromised in a region where it rains 50 inches a year, and Southwest Alaska is one of the most seismically active zones on the continent. The 1964 Alaskan earthquake registered magnitude 9.2 — 32 times the strength of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

To understand the potential catastrophe for the greatest run of salmon on Earth, look no further than another Canadian mining company’s tailings-dam disaster in 2014 at Mount Polley, British Columbia. Twenty-four million cubic meters of mine waste roared down Hazeltine Creek and into Quesnel Lake, devastating each. You can see the resulting cataclysm on video. Although the long-term consequences remain unclear, that uncertainty is precisely why so many oppose Pebble Mine. After all, Dynasty says Pebble Mine will be safe, but that’s what the Mount Polley mine owners said, too.

Not incidentally, Imperial Metals, owner of the Mount Polley mine, suspended the mine’s operations in January 2019 due to declining copper prices — yet one more reason to reject the assertion that Pebble Mine is an economic necessity.

Perhaps recognizing a loser when they see one, four mining giants, including Mitsubishi and Rio Tinto, have backed out of the Pebble Mine project over the years, leaving questions of capability and liability with the smaller, less-well-capitalized Northern Dynasty firm. The federal Environmental Protection Agency at first rejected the project, finding in 2014 that “mining the Pebble deposit would cause irreversible damage to one of the world’s last intact salmon ecosystems” and recommending restrictions on development in Bristol Bay. But the mine was resurrected by Trump’s first — and disgraced — EPA director, Scott Pruitt in 2017, and the agency’s proposed safeguards were officially dropped earlier this year. Now the Army Corps’ environmental impact statement is criticized as egregiously flawed.

Surveys show that a strong majority of Alaskans oppose the mine, though its sponsors have predictably garnered support of state officials. Native Alaskans oppose the use of their land for the road and pipeline. Bristol Bay’s largest landowner, Bristol Bay Native Corp., whose shareholders are the area’s native people, is unequivocal in its objections to the Army Corps’ EIS: “[It] does not and cannot support the conclusion that the proposed Pebble mine and Bristol Bay salmon can coexist.” Alaska natives have been joined by commercial fishermen and a coalition of conservation organizations that vow to appeal federal permits.

As chair of the House Committee with oversight of the Army Corps and the Clean Water Act, Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) favors protection, saying: “There is no way to compensate for the loss of one of the last pristine wild salmon runs in the world and for the destruction of land that many Alaska native nations have called their home for millennia. We cannot get this wrong.”

If the Army Corps and EPA do get it wrong and approval is granted for the Pebble Mine this fall, protection would depend on a Joe Biden presidency to reset federal policy away from foreign profits and toward fishery conservation and the view of a majority of Alaskans. The reelection of Donald Trump, conversely, would assure an extended conflict with the clear risk of ripping apart not only Bristol Bay, but Alaska’s social fabric as well. The aftermath could handicap generations to come.

The state of Alaska is far beyond the horizon for most Americans. Few of us will ever see the wonders of Bristol Bay and its wild headwaters nourishing the world’s most prolific runs of salmon, but if they are lost, we will have failed to protect what truly makes America great.

Tim Palmer is the author of “Pacific High: Adventures in the Coast Ranges from Baja to Alaska” and other books. Char Miller is professor of environmental analysis and history at Pomona College and author of “Hetch Hetchy: A History in Documents.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.