- Share via

An uneasy calm had settled over Los Angeles a few weeks after the 1992 riots sparked by the acquittal of four police officers in the brutal beating of motorist Rodney King, but the Los Angeles Times newsroom was still in full adrenaline mode. Editors brainstormed ideas while reporters rushed in and out, pursuing stories on the effects of the civil unrest.

It was an exhilarating time to be an ambitious young Black journalist at The Times.

It was also wrenching and perilous.

When live shots of the uprising, including the near-fatal beating of truck driver Reginald Denny, hit the airwaves April 29, several Black reporters who normally worked in The Times’ suburban sections were hastily summoned to the downtown newsroom. They were quickly dispatched to “hot spots” around the city, replacing white reporters who feared they would be in harm’s way if they ventured out into the streets.

I was one of those recruits.

Our reckoning with racism

As the country grapples with the role of systemic racism, The Times has committed to examining its past. This project looks at our treatment of people of color — outside and inside the newsroom — throughout our nearly 139-year history.

The sudden diversification of the predominantly white news staff eventually ignited its own flare-up. Then-assistant business editor Linda Williams angrily accused editors of sending Black reporters into danger, making them “cannon fodder.” The charges revived long-standing criticism of The Times’ historically poor record of hiring Black journalists. Tensions escalated, casting a shadow over the newsroom.

The heated turmoil of that era mirrors the current firestorm at The Times as it faces yet another day of reckoning over failures to follow through on repeated pledges over the last several years to hire more Black writers and journalists of color. The hot-button issue has once again sparked intense dialogues, made more complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has forced management and staffers to grapple with the dilemma in Zoom meetings and internal emails rather than being face-to face.

In many ways, the inequities are even more alarming and emotions have reached a fever pitch, much like in 1992.

I was in my mid-30s then, and before the term “cannon fodder” was uttered, concerns about being “on the firing line” were secondary. When I was called downtown for riot duty, I was so excited. My paper needed me, and the chance to cover one of the biggest stories in L.A. history was preferable to my regular gig in the San Fernando Valley section — writing about homeowner meetings and city councils.

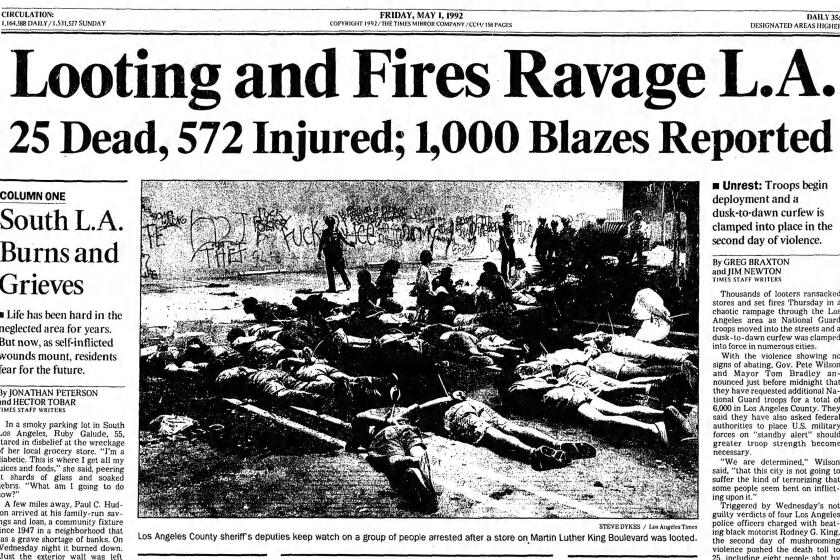

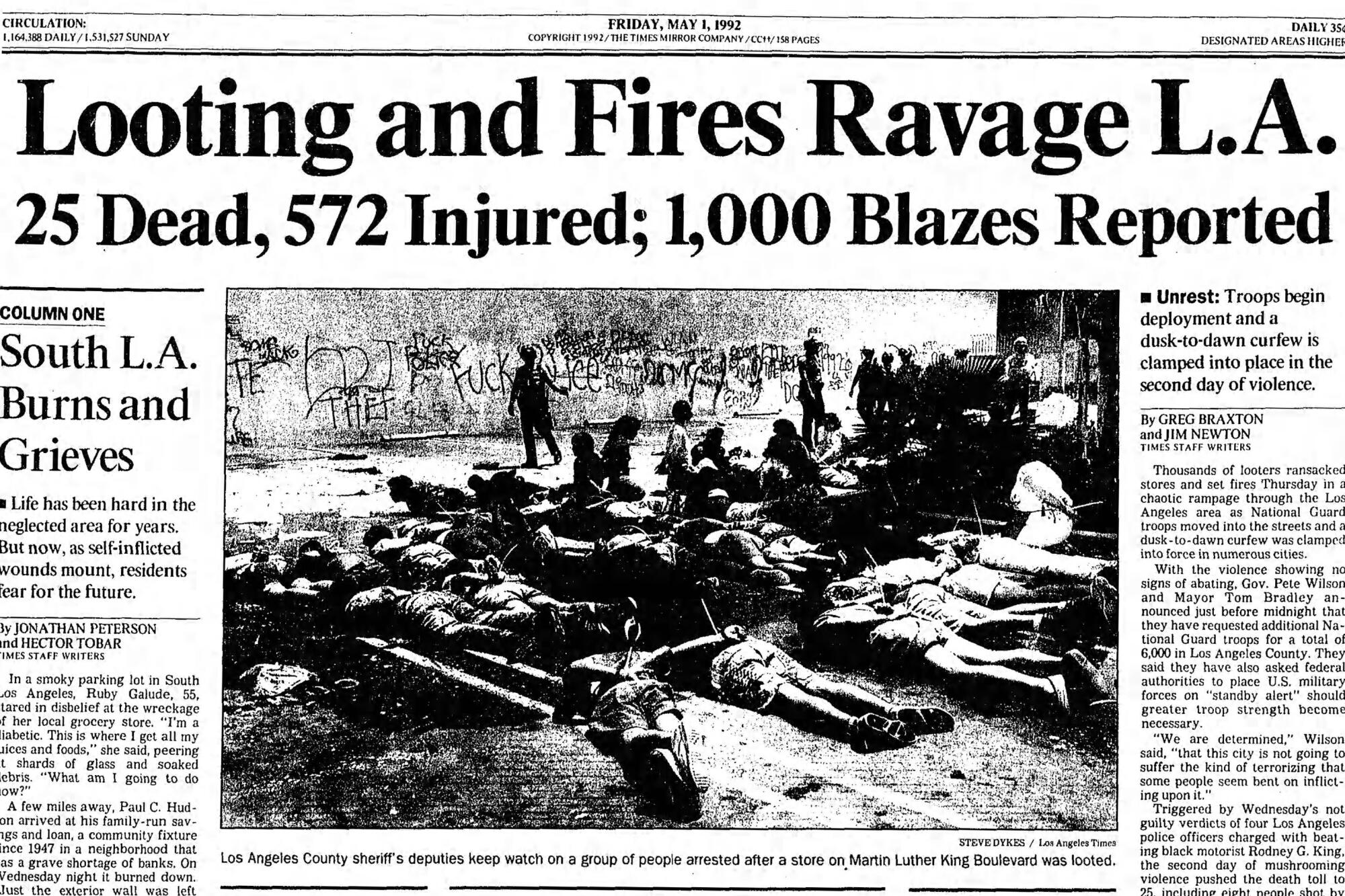

All of a sudden, I was in the thick of the city’s chaos. After being out until dawn that first night, I was thrilled to see my byline — as well as Jim Newton’s — on a front-page story under the headline “Looting and Fires Ravage L.A.” In the following days, I worked on a flurry of stories, several of which landed on A1. The Times’ coverage of the event earned the paper a Pulitzer Prize for spot news reporting.

Just shy of marking my 10th anniversary at The Times, I was sure that my initiative and enthusiasm, along with praise from colleagues and editors, would pay off and lead to a promotion from the Valley to the main news operation. I was not alone in my aspirations.

Other Black reporters from the suburban sections were also trying to make the best of their temporary assignment, working at desks that did not belong to them.

One day, as I was working on a story at one of those desks, I felt a hand on my shoulder. Standing above me was Metro editor Craig Turner. He had the look of a college professor — freshly pressed shirt and tie, wire-rim glasses. He had been on vacation when the riots erupted but had returned within a matter of days.

“Hey, Greg,” he said. “Starting Monday, you go back to the Valley.” Before I could reply, he flashed a slight smile, turned and left.

For a few moments, I sat paralyzed, my eyes welling up, my surroundings a blur. With the lightest of touches, Turner and his casually delivered pronouncement had crushed me. Without a word of appreciation or a chat about my future, I had been unceremoniously dismissed, reduced in a few seconds from being a valued participant in the riot coverage to just another Black journalist with an uncertain future.

The pain of that moment stayed with me when I departed the Valley a few months later to join the Calendar staff, which covers arts and entertainment. It flared anew when Turner joined Calendar several years later as one of the top section editors. Although we would talk occasionally about stories, I never had the courage to bring up the past with him, reasoning that he probably didn’t even remember that moment.

My time in Calendar, where I’ve been a reporter and an editor, has been, for the most part, rewarding. I’ve specialized in examining diversity — and the lack of it — along with cultural images on television. One TV network has repeatedly accused me of having an agenda, so I must be doing something right, and work by my colleagues has resulted in high-profile stories and awards.

It was time to revisit that history and strip it of its power.

— Greg Braxton

But as I look around me every day, the cultural climate of the newspaper is still troubling. I am the most senior African American journalist at The Times. But there are so few who look like me, and there is almost no one who can relate to my present and past experience. Listening to the current, impassioned testimonials and the depth of emotion from colleagues who are also disturbed about the lack of inclusion and coverage is an illustration of a dangerous cycle.

It has also been a sharp reminder of that fateful moment in 1992. But this time, instead of again giving in to the ache, I saw a chance to end its continuing hold. It was time to revisit that history and strip it of its power.

That meant finally having a frank conversation with Turner, almost 30 years after he placed a hand on my shoulder.

Our exchange, which took place over the Fourth of July holiday, was both unsettling and enlightening.

What’s often lost in the enormity of relentless media coverage of the fiery and impassioned issue of race in this country is the recognition of the humanity behind the hurt, the complex cultural interactions in workplaces — sometimes influenced by discrimination, unconscious bias or insensitivity — that can wound or take a wrong turn. Those wounds may recede with the passage of time, but the scars remain.

•••

As the U.S. confronts institutional racism, the Los Angeles Times is examining its own record on race and racism in the newsroom and its coverage.

Those scars marked my father, a proud Black man who was successful by any measurement — he worked more than 30 years as a civil engineer at the Department of Water and Power, making enough money in his early career that my mother was able to stay home and take care of their two children. After his retirement, he moved the family to fashionable Ladera Heights, where he lived comfortably until his death in 2017 at age 95.

But those accomplishments and his unquenchable love of life, family and USC never fully erased the racial traumas he suffered while serving in the Navy — and at the DWP.

Eugene Green Braxton was a rarity in that city agency — an African American civil engineer with a master’s degree from a top university. But being a rarity didn’t mean he was valued.

I can recall a holiday season during my childhood when something seemed off, when my father was putting on a brave front during a time of deep distress. I had no idea at that time that a white supervisor who disliked him because of his race had blocked his path to a promotion. My father had to ask a Los Angeles City Council member, the late David Cunningham Jr., to intervene on his behalf. He finally got the promotion he deserved.

(A cousin, the late Frank Braxton Jr., also faced discrimination while making history as the first Black artist to work in the animation industry. While making valuable contributions to classic cartoons such as “Fractured Fairy Tales,” “George of the Jungle,” Charlie Brown specials and other projects in the 1950s and 1960s, he was regularly challenged by institutional racism.)

Despite my father’s victory, his wounds continued to bleed for decades. At family and social gatherings, he would often launch into a lengthy account of those harrowing incidents. His accounts were so vivid, so precise and detailed, it was as if he had gone back in time. But I would sometimes feel uncomfortable when he would start in on one of his recollections, fearing the stories were spoiling the light mood and testing the indulgence of his listeners.

Six years ago, the two of us spent the Fourth of July at the house of my good friend and colleague Doug Smith and his wife, Jackie. They were quite fond of my father, and the feeling was mutual. After fireworks and dessert, we were relaxing in the dining room when my father started talking about the DWP and his ordeal. The Smiths listened quietly as the monologue stretched late into the evening. I worried that he had hijacked the conversation — again.

It’s taken me until now to realize that his detailed reflections of that evening and those other occasions where he seemed to go back in time were his way of coping with the damage that still haunted him, and how sharing that pain with people he loved and trusted was a form of healing therapy. It fills me with deep shame that my shortsightedness blinded me to the depth of his heartache. I would give anything now to hug and console him and tell him that I finally understand.

“Jackie and I were riveted,” Doug Smith told me when I asked him recently about that evening. “It wasn’t just the story, but Mr. Braxton’s telling of it, that impressed us. He spoke as if he was relating the experience of another man, evoking the pain of injustice while holding his own rancor in a secure place from which it could not diminish his lasting pride and satisfaction in the work he loved. That was a gift.”

Impressed with the current intensity of Times journalists — white and nonwhite — who are demanding inclusion, recognition and improvement on the diversity front, I realized that I could have what my father never had — my own day of reckoning.

•••

Turner retired about eight years ago. We would run into each other occasionally at theater openings at the Music Center. I suppressed discomfort, and our brief conversations were pleasant, innocuous.

I emailed him July 2, saying that I wanted to talk about The Times in 1992, giving few specifics about what I wanted to write. He quickly responded, and we agreed to talk the following day.

As the assigned time approached, I became more anxious. My hands were trembling a bit. I had no idea how Turner would respond. Would he lash out? Would he be defensive? My stomach was tied in knots as I dialed his number.

The first few minutes were filled with small talk — gossip about The Times, thoughts about life during a pandemic. I finally took a deep breath and stated the purpose of my call. I was writing about my experiences covering the ’92 uprising and revisiting our interaction. My words did not come easily, but after some stammering, I finally got them out.

When I finished, Turner spoke, his tone just as smooth as it had been that fateful day.

“I don’t remember that conversation,” he said. “But I apologize for not being as understanding or as thoughtful as I should have been. One of my failings as a manager was I was not as empathetic with people who worked for me as I should have been. I was very focused on efficiency. I learned from that experience and I feel I was a more empathetic manager in later years. But I definitely should have thought about what those words meant to you.”

He added: “I wish you had brought this up earlier when I came to Calendar. It would have been an important conversation for both of us.”

We talked a little more and then hung up. A few minutes later, an email arrived:

“Greg, let me just add that what I should have done was thank you for your work and the hardships it entailed and set up a time when we could have talked longer about your experience. That’s what I would have done later in my career. As my wife just said when I related our conversation to her: it’s a shame our more experienced selves can’t go back and advise our younger selves what to do. Stay well. Craig.”

Months have passed since then, and the world seems to have turned upside down several times. But when I least expect it, that summer conversation can still flash in my head like a sudden interloper. I respect its power, startled by the way it can make me catch my breath without even realizing it. At times my eyes fill. But there is no longer anger or pain. Instead, I exhale deeply, grateful that the 1992 encounter no longer has the capacity to haunt or hurt me.

We are living in horrific times. Every day we are besieged by difficulties and hardship, and toxicity permeates the news. The raw emotion and the relentless battle to improve our situation and our world are justified. They cannot, and must not, stop, but we must also never give up on finding light in the darkness. If we can make that effort, we can hopefully find that inner strength that will lead us to a space where we can discover calm — easy and uneasy — redemption and healing.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.