Op-Ed: How to fix a National Register of Historic Places that reflects mostly white history

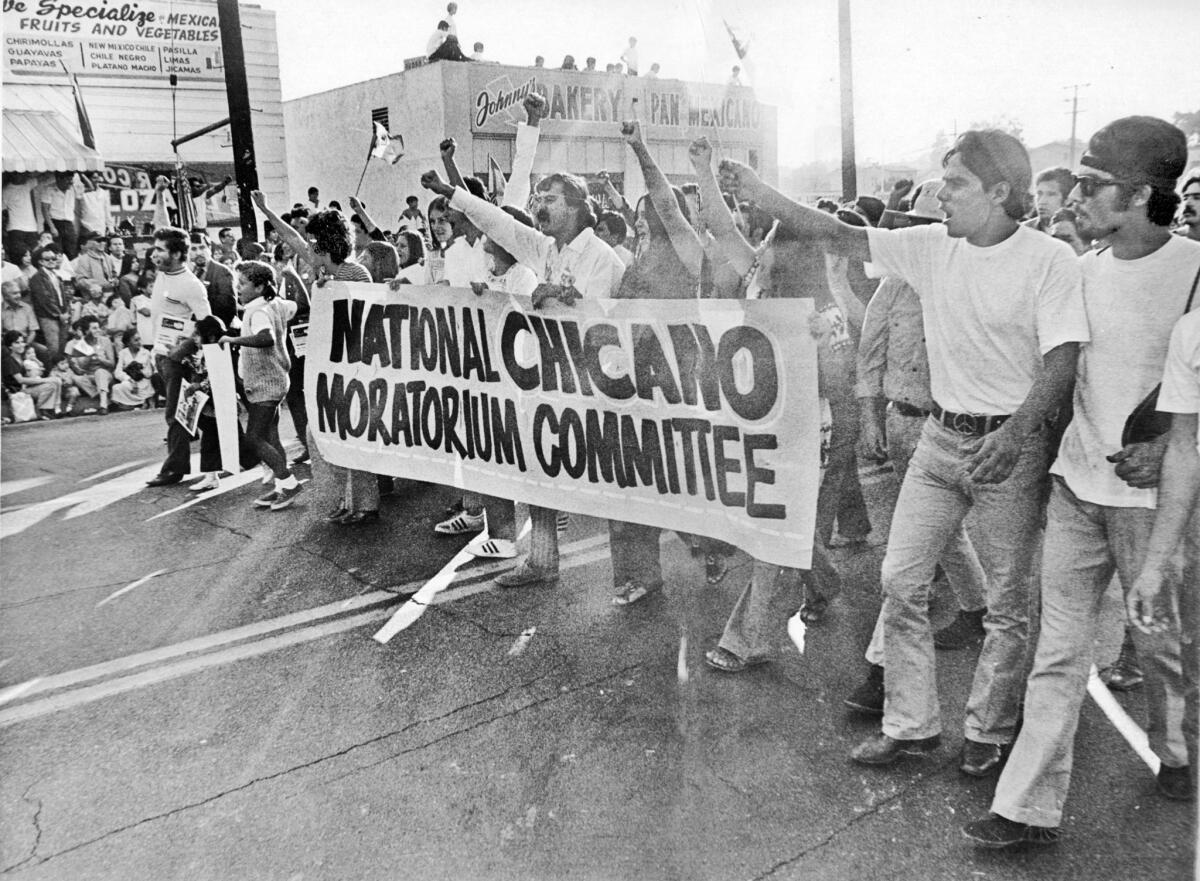

Fifty years ago, tens of thousands of people marched through East Los Angeles in a series of demonstrations as part of the Chicano Moratorium movement to protest the Vietnam War and its toll on Mexican Americans. Hundreds were arrested, and several were killed, including L.A. Times journalist Ruben Salazar.

Those marches are an indelible part of Angelenos’ struggle for racial equality, but their national significance was not formally recognized until last month, when several key sites along the march routes were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Credit is due to the Los Angeles Conservancy and countless Chicano studies scholars for advocating for their listing. But it is important to put this victory in perspective.

Less than 8% of sites on the National Register are associated with women, Latinos, African Americans or other minorities. The César E. Chávez National Monument, established just eight years ago, was the first unit in the National Park System commemorating any aspect of modern Latino history.

The reason for this underrepresentation is an overly technical, legalistic approach to determining what merits designation. Historic registers at the federal, state and local levels only include places satisfying specific criteria. Typically, laws require that a site satisfy two elements for listing: significance and integrity.

Significance can result from an association with an important person or an important event. But historical accounts predominantly feature the accomplishments or events related to white, usually wealthy, people. A site can also be significant if it showcases emblematic architectural or engineering styles or techniques. But in the canon of worthy architectural styles, European styles, not vernacular techniques, dominate.

Given the political and cultural impact of the Chicano Moratorium protests, I was not surprised that associated sites were deemed to be significant. However, I was pleasantly surprised that they overcame the more difficult barrier, integrity — which might have been denied because the sites have changed so much over the last 50 years.

The events and emotions of the Chicano Moratorium still reverberate in L.A.’s Latino community 50 years later.

Usually, integrity is defined to be the ability of a resource to communicate its significance. To have integrity, a site must not have been significantly altered. It’s not typically supposed to be moved, and it’s supposed to have most of its original materials. But many significant sites associated with minorities have been altered, or even moved. Often, the materials from which they were constructed don’t endure for all that long. While Monticello has endured, its slave cabins have not. Such sites are also more likely to be threatened by neglect and environmental destruction.

The historic headquarters of the League of United Latin American Citizens in Houston is just one example of this phenomenon: It was nearly lost before a national effort to save it. Similarly, in his survey of César Chávez-associated sites conducted for the National Park Service, Ray Rast, a historian at Gonzaga University, noted that physical alterations could regrettably pose a barrier to formal designation. As another example, sites associated with the Black Lives Matter protests will no doubt change so much over the next few decades that they might well be rejected for listing if the current standards of historical integrity were applied.

Designation can bring both recognition and legal protection to listed sites. National Register properties are eligible for the federal historic preservation tax credit, and many state register properties are eligible for state-level tax credits. National and state register sites may be protected by laws that require that their status be either taken into account during the planning of public projects or protected from harm.

Designation, however, does not guarantee protection. In the “11 Most Endangered Historic Places” identified by National Trust for Historic Preservation this year, all but one were either listed on historic sites or determined eligible for listing. San Antonio’s Alazan-Apache Courts, a public housing development that served Mexican American families, is the exception and it is slated for demolition. The other sites, such as Pittsburgh’s National Negro Opera Company House, are in an advanced stage of deterioration or threatened by development. So even after placing a site on a register, we must be vigilant to ensure that the site benefits from the legal protection designation affords.

As we raise awareness of emblematic and threatened sites left out of the national narrative, we should rethink how we determine whose history is protected to begin with. The criteria and process for historic designation must be retooled. Designation applications currently require detailed architectural or social histories of a site. These requirements are daunting for ordinary people and no doubt reduce the number and diversity of nominations. Oral histories and cultural narratives, and less-technical descriptions of sites’ meaning, should suffice to prove significance.

We may also want to consider loosening the definition of integrity. At a minimum, we might consider that some alterations to sites enhance authenticity, not diminish it.

Preservationists have started to see past the formalities that have too long prevented us from recognizing diverse histories. But we must go further to tackle the legal structures that devalue the stories we all need to hear.

Sara Bronin is a Mexican American professor at University of Connecticut Law School, specializing in historic preservation law. She serves on the board of Latinos for Heritage Conservation.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.