Editorial: Let L.A.’s feral cats get neutered and die out

Outdoor cats are controversial. Whether lost or abandoned strays or unsocialized feral cats, they roam cities and towns around the world, surviving on garbage dumps, small prey, and the kindness of strangers who put out food for them.

To many animal welfare advocates, these cats are vulnerable — they live a scant few years, falling victim to wild predators, speeding cars, or rat poison they ingest. But to others, outdoor cats are opportunistic predators that hunt not only birds — an estimated 1.3 billion to 4 billion — but also lizards and small rodents.

Everyone agrees that cats shouldn’t be roaming outdoors. The question is how to reduce that population in a humane way.

As most animal welfare experts recommend, Los Angeles wants to embrace the practice of trap-neuter-return (known as TNR). When the cats are neutered or spayed, an ear tip is notched. Volunteers and rescue groups mostly carry this out and also feed colonies of cats.

But in 2008, wildlife advocates sued the city, arguing that a TNR plan should not go forward without an environmental assessment first. A judge agreed and issued an injunction.

Three years ago, the city proposed a Citywide Cat Program that would include support for TNR but would also allow households to take in as many as five cats, up from the current limit of three.

Now, after a three-year study, the city has issued an environmental impact report, and the City Council approved it Dec. 8, clearing the way for the cat program to finally go into effect.

Under the program, the city plans to offer 20,000 vouchers annually for free spaying and neutering to experienced volunteer trapping groups. The city estimates that the number of cats on the street will go down from 342,915 (a figure arrived at through a population model) to 296,196 — in 30 years. That’s nearly a 14% decrease. The city says its plan would prevent the births of more than a million kittens over that time.

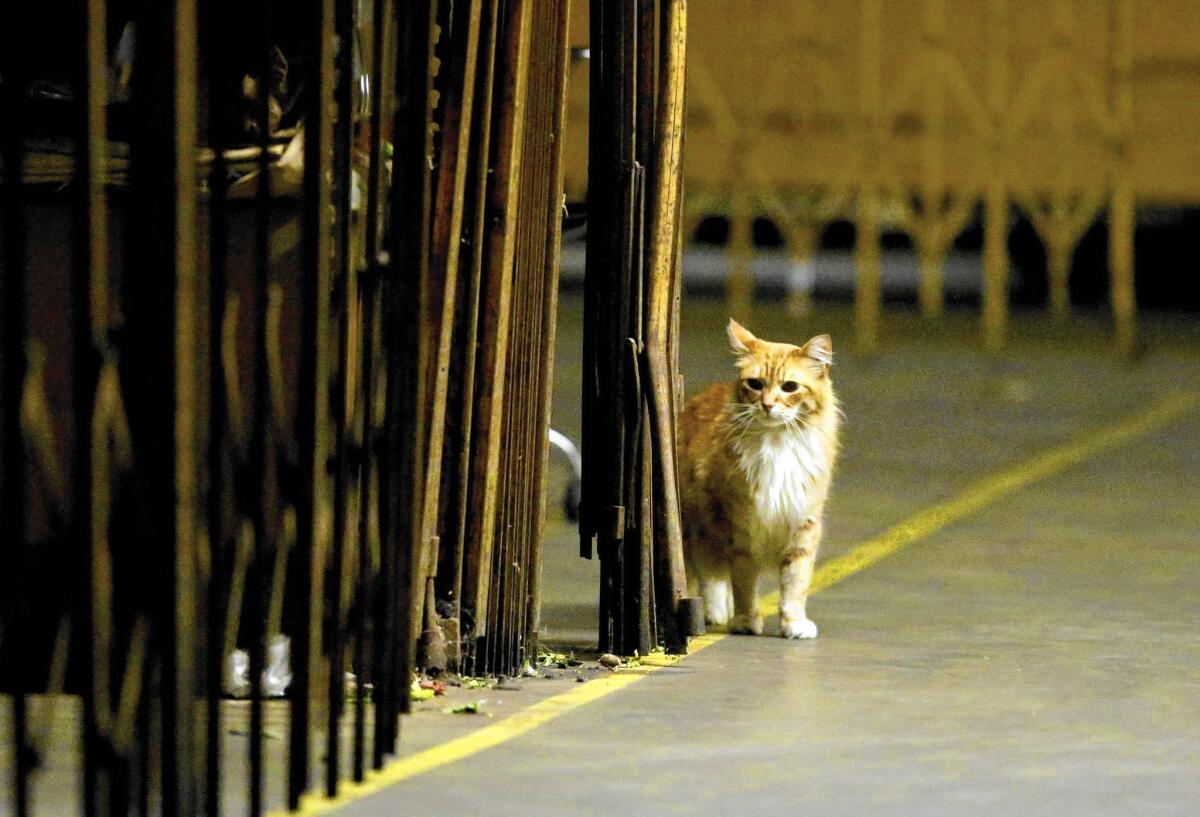

Meanwhile, the city would continue to offer low-income residents vouchers to get their cats fixed. The city would also start a Working Cat Program that would relocate some feral cats (after they are trapped and neutered) to barns, warehouses and other venues where the felines act as deterrents. And the city plans an education campaign to stress the importance of altering pets and keeping cats indoors at all times.

It’s a good plan, but there are already objections from groups seeking to protect native species, especially birds.

They say that in some jurisdictions with TNR initiatives, the number of cats sometimes even goes up, as (irresponsible) cat owners dump cats into colonies fed by volunteers. (Cat researchers contend that only happens in the short term, when a TNR program starts.) The state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife has criticized elements of the plan, saying the analysis did not sufficiently address the potential impact on bird species in environmentally sensitive areas like wetlands. (The city says it was required to show only that the overall plan would not worsen the environment.)

These objections are understandable, but the evidence supports the city’s plan.

In Cook County, Ill., caretakers of cat colonies are allowed to do TNR and microchip and feed the cats as long as they register and do annual counts of the colonies. Chicago has an estimated 200,000 feral cats; since 2008, volunteers have gotten more than 40,000 altered, prompting a significant decline in strays being brought into shelters.

According to numerous studies , TNR efforts have reduced outdoor populations of roaming cats, though the programs can take a long time to show results. On a two-mile stretch of the San Francisco Bay Trail where TNR was employed, from 2004 to 2020, a total count of 258 cats went down to one. A TNR program in Newburyport, Mass., eliminated all of the town’s more than 300 waterfront cats in 17 years. (A third that were trapped and neutered were able to be adopted out.) In Randolph County, N.C., a study of more than 100 feral cats over 11 colonies showed that among the cats that were neutered and returned, one sterilized colony went extinct after 31 months and several more consisted of five or fewer cats after seven years.

One environmental policy expert and critic of the plan suggested the city use all of its spay and neuter vouchers on pet cats to stop them from reproducing if they get outside. But the city dismissed that alternative and others, including the most grim idea: trapping cats and killing cats. Rounding up tens of thousands of outdoor healthy cats to either kill them or put them in shelters — where they would almost certainly be euthanized — would be barbaric.

The city’s plan will take time to have an impact, but it’s a good start. To be most effective, private fundraising will be needed to pay for even more vouchers, and an aggressive campaign will be needed to educate the public about the need to keep cats indoors.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.