Column: The answer to equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines is hiding in plain sight

People were bundled against the chill last weekend as they arrived at the Venice Family Clinic. The clinic had set up six white vaccination tents in its ground-floor parking lot, but they and the small propane heaters set up for warmth were weak foils against the wind that whipped through the open structure.

Still, everyone was pretty cheerful. About 150 patients were scheduled for their second doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, and 80 volunteers — including both practicing and retired doctors and nurses — had turned out to help.

Patient No. 79 was Julia Limon, an 87-year-old grandmother whose son Jose Cruz had driven her to Venice from Riverside, where she’s been staying with him on and off since her husband passed away.

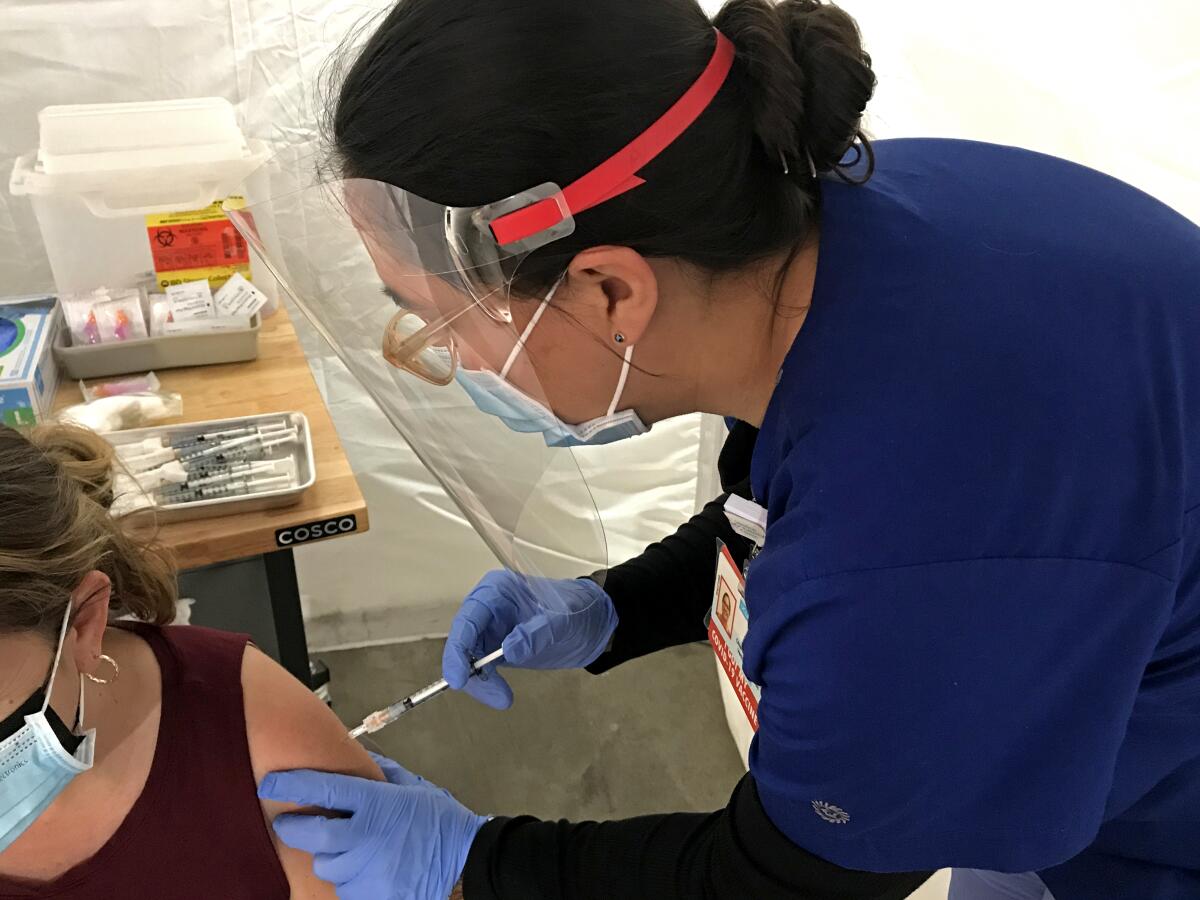

“Do you have any allergies?” Anita Zamora asked Limon in Spanish as Limon rolled up her sleeve for the jab. Zamora, a nurse, is chief operating officer and deputy director of the Venice Family Clinic.

For months, she has devoted at least one entire workday each week to trying to secure scarce vaccines for her patients, mostly people of color who are dependent on government healthcare because they live below the federal poverty line. About a sixth of the clinic’s 27,000 patients are experiencing homelessness at any given time.

Zamora’s patients are exactly the kind of people current vaccine policies have been failing: They contract the coronavirus at higher rates, they have a higher rate of death from the disease, and yet they are receiving vaccinations in much lower numbers than they should.

Why is that?

“Our patients don’t have transportation to get to the mega-sites,” said Zamora, “or the time or the access to get on the internet and try to schedule that online appointment the moment it becomes available.”

And yet, community health centers, which care for some 1.7 million poor people in Los Angeles County, seem to have been left out of the state’s latest plan for vaccine distribution. A new “third party administrator” — Blue Shield of California — has begun taking over vaccine distribution for the state in an effort to centralize what until now has been a piecemeal approach.

As of now, it appears that community clinics are not part of the distribution plan. Blue Shield, which has wide latitude to select the providers to receive the vaccines, has said it will create an algorithm to increase equity.

But why try to solve a problem that already has a solution? Send the vaccines to the places where people who need them already come for care.

Stat, the health and medicine news website, recently published a map showing the close correlation between the parts of L.A. County with high rates of COVID-19 and the locations of community clinics. The overlap is stark.

“Our health centers can deliver more doses than that FEMA site at Cal State L.A.,” said Louise McCarthy, president and chief executive of the Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles County, which represents 64 nonprofit clinics with 350 sites located in the hearts of the neighborhoods they serve. “We need to be seen as a network. Our patients will not be easy to reach with a mass vax site. We are trusted providers who can deliver the doses where they belong.” (The Cal State L.A. site, a collaboration between the state and federal government, can deliver 6,000 doses a day if the supply exists.)

McCarthy’s frustration was palpable: “It’s like we are on the stairs and they are on the escalator.”

Last week, McCarthy sent a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom, pleading for him to make sure that community health centers are included in the new distribution scheme.

“Accessibility is more than just geography,” she wrote. “It must also consider people’s means of transit, language, culture and sensitivity to concerns such as immigration status, gender identity or sexuality. Just because there is a vaccination location geographically nearby does not necessarily mean it is accessible. Equity should not be forsaken for volume or expediency.”

The California Primary Care Assn., a coalition of 1,370 community health centers that serve more than 7.4 million Californians, sent a similar plea to the governor last month.

So far, Newsom has not responded, McCarthy told me.

In the Venice Family Clinic parking lot, Zamora was about to deliver a first dose of vaccine into the arm of Juan Ayala, a 66-year-old janitor at A Bridge Home, the local shelter whose residents are also Venice Family Clinic patients. Ayala told her about some of his recent health problems.

“He’s the kind of person we want to make sure gets the vaccine,” said Zamora, “especially someone who does custodial work, since he’s exposed to bodily fluids.”

As I thought about the obvious solution the coalition of clinics is proposing to getting vaccines into the arms of people who need them most, I couldn’t help but think about that famous story attributed, perhaps apocryphally, to Willie Sutton, the bank robber.

“Why do you rob banks?” he was asked.

“Because that’s where the money is,” Sutton supposedly replied.

So let’s toss out the algorithms and the high-minded rhetoric about equitable distribution and get the vaccines to community clinics.

After all, they are where the patients are.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.