Op-Ed: Migrant children are being sheltered at Pomona’s Fairplex. It’s not the first time the fairgrounds has housed detainees

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the billboard along the eastbound 10 Freeway at Dudley Street in Pomona invariably promoted events at the Fairplex that included expos and one of the largest county fairs in the United States. Today, something far more serious than carnival rides and arts and crafts competitions is occurring at the Fairplex. As of May 1, it has been used as a temporary shelter for more than 500 migrant children who have arrived unaccompanied at the U.S.-Mexico border since March.

We have a personal connection to the fairgrounds. We both work within five miles of the Fairplex. The roots of Summer’s Latino family in Pomona reach back more than 100 years. We’re both descended from communities of color, some of whom endured detention, and others who picked lemons in California’s fields and worked in the state’s packing districts. This repurposing of a Pomona landmark brings up painful memories of our ancestors’ experiences with California’s legacy of exclusion and detention.

Since 1922, the Fairplex — then called the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds — has been home to the L.A. County Fair. But after 19 public expositions, the grounds temporarily served a different purpose, one that has largely remained in the shadows.

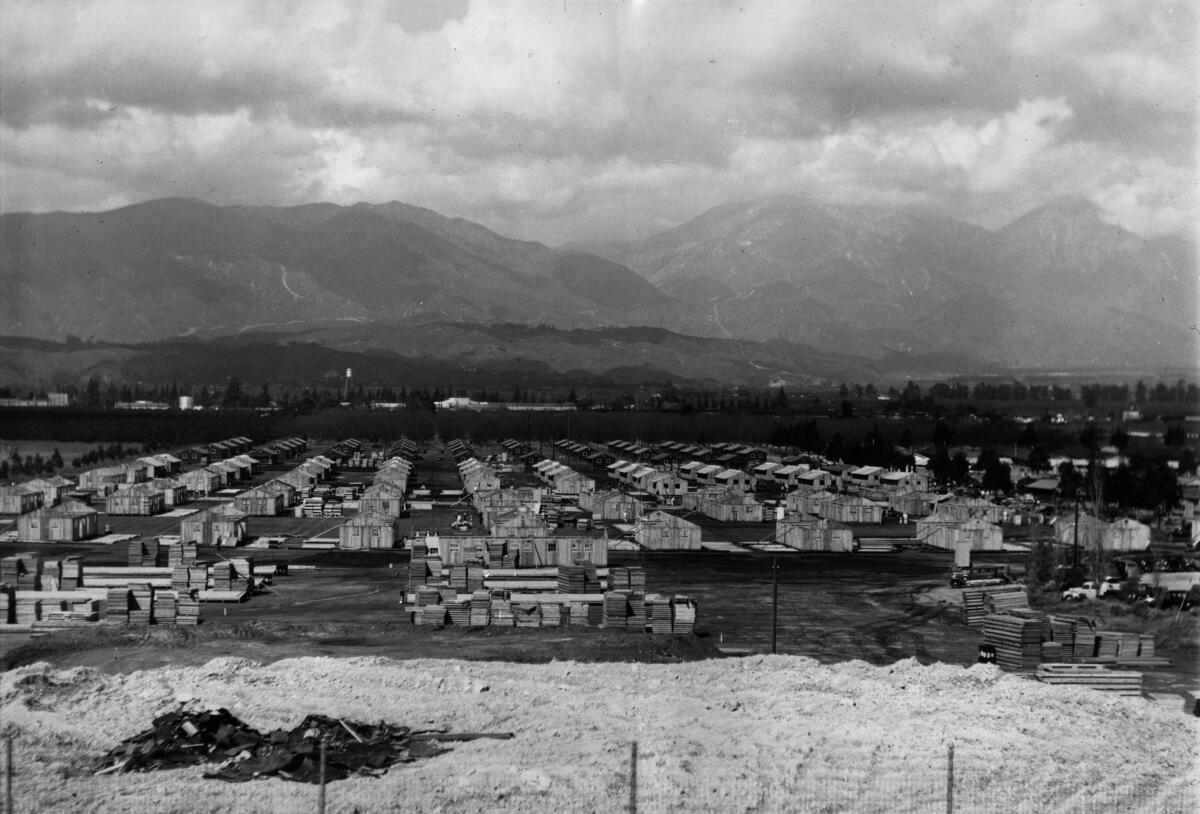

It became one of 15 locations in California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona that temporarily housed more than 92,000 people of Japanese descent who were detained until more permanent incarceration camps were built. At the height of World War II, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which gave the military authority to remove native-born and longtime residents of Japanese descent from the Pacific Coast — anyone who was at least one-sixteenth Japanese fell under the order. As a result, the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds became home to the Pomona Assembly Center, a stop on the way to long-term incarceration.

Between May 7 and Aug. 24, 1942, the fairgrounds housed more than 5,400 detainees. The majority of the Japanese Americans held there came from downtown and East Los Angeles while others arrived from as far as Santa Clara County and San Francisco. Former detainees recall how they were dehumanized: their names replaced by identity numbers, their families packed into rooms with paper-thin walls, and outside, armed guards staffing security towers.

In 2014, Summer’s great-aunt told her that one of her great-uncles, who lived locally, was among those employed to build the 309 barracks at the Pomona Assembly Center that housed the detainees. They also built laundry buildings, bathhouses, mess halls and other facilities. Summer tried to learn more about her relative’s life but could uncover little from family and historical records, not even her great-uncle’s name.

The Pomona Assembly Center and Japanese incarceration camps like Manzanar that came later are part of California’s shameful history of immigrant detention, expulsion and exploitation, particularly to those of color. The creation of the assembly centers can be traced to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the first U.S. law that prohibited immigration based on race. It fueled future anti-Asian sentiments and ushered in a series of laws restricting and prohibiting immigration that laid the groundwork for the executive order that led to the egregious need for assembly centers.

Between 1910 and 1940, hundreds of thousands of immigrants from more than 80 countries came through the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay for processing, detainment and sometimes interrogation. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the majority of those detained were Chinese. Among those immigrants were Kathy’s grandparents, Marie and Gim. They were minors at the time, and never saw their mothers again after they were released from Angel Island — one more example of the sad history of familial separation through immigrant detention.

Like Pomona’s fairgrounds, Angel Island also played a part in California’s confinement of Japanese Americans during World War II, serving as a temporary detainment center for almost 700 Japanese Americans before they were sent to incarceration camps.

Today, the Fairplex and other designated mass shelters are intended by the government to be welcoming spaces; temporary stops in the Biden administration’s efforts to reunify migrant children with their families. Southern California’s shelters are among almost 200 facilities that house about 21,000 unaccompanied migrant children across two dozen states. But U.S. immigration law defines a family as children and their parents or legal guardians, which means some minors who arrived at the border with older siblings, grandparents or other relatives have been designated as unaccompanied and sent to shelters.

The immigration debate poses a moral dilemma for America.

It is essential that leaders and immigration advocates ensure that today’s mass shelters don’t become part of this country’s legacy of detaining young people of color. It was in the name of “racial purity” that minors like Marie and Gim were detained at Angel Island Immigration Station. National security was invoked when Japanese Americans were incarcerated at the Pomona Assembly Center.

As we consider the children currently housed at the Fairplex, and our ties to those grounds and its oft-overlooked role in California’s history of immigrant detention, we urge our leaders to seek better ways of protecting migrant children. That would be in keeping with the hope spelled out on a plaque on the fairgrounds: “May such injustice and suffering never recur.”

Kathy Yep is a professor of Asian American Studies at Pitzer College and a coauthor of “Dragon’s Child: A Story of Angel Island.” Summer Espinoza is an executive assistant at Pitzer and a former archivist at the Go For Broke National Education Center, which preserves the history of Japanese American veterans of World War II.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.