Editorial: Post-pandemic, let’s make capitalism more equitable

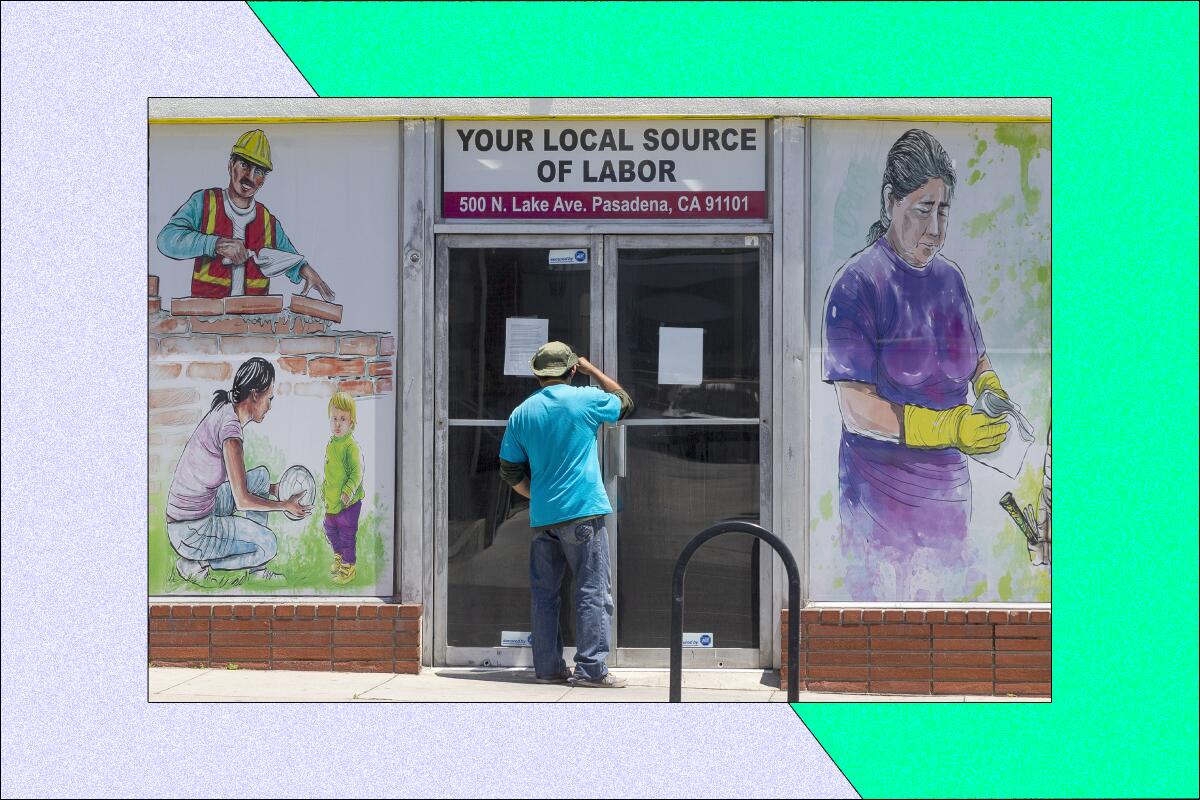

The sudden COVID-19-driven shutdown of workplaces early last year cost more than 33 million people their jobs over a seven-week span. Governments rushed to try to help, partly by funneling cash to keep countless households afloat, but the damage was severe, especially to nonwhite workers and those already on the low end of the income spectrum. Even now, as jobs come back, the pain continues for people left with higher personal debt, deferred rent payments and other financial problems.

Unfortunately, this financial meltdown was the second time in just over a decade that millions of people have been thrown out of work. Those shocks to the economy have cast in sharp relief just how tenuous some jobs can be, particularly in a consumer-driven economy. Yet, for better or worse, we’re stuck with our capitalist system. But that doesn’t mean we can’t find ways to make it work more equitably for everyone, particularly those most vulnerable to layoffs and financial hardship.

As the gap in income equality widened over the past few decades — and put a drag on social mobility — it became imperative that we find ways to shore up the fortunes of those benefiting the least, or only sporadically, from our economic system. Notably, people who lose jobs during a downturn are often the same people who don’t fully share in the wealth generated during upturns. Jobs and careers and the ability to accumulate wealth are part of a complicated set of relationships weighted by class, race, gender, geographic regions, educational levels and access to capital.

It’s no coincidence that income inequality worsened as union membership and power dwindled under shifting federal protections, the spread of “right to work” laws in the South and Midwest, concerted anti-union efforts by employers, and the transition of the economy away from manufacturing to services. California is a relatively strong labor state with protections for collective bargaining and other workers’ rights augmenting federal standards under the Depression-era National Labor Relations Act, yet union membership here, driven by the public sector, is still about 15% of the work force — higher than the national average of about 10% but well below the peak of 70 years ago. when about a third of the non-farm workforce nationwide was in a union. Nevertheless, two-thirds of workers support unions.

We can do more to shore up collective bargaining and reimagine the role played by unions, which historically have been a democratizing force for workers and a counterweight to the cultural deification of CEOs. Our union system is enterprise-based — unions organize workers for a specific company. In Europe bargaining often is done by sector, so unions are able to negotiate basic contract terms across an industry, a lift-all-boats approach.

Federal law recognizes workers’ rights to organize unions, but the laws and regulations guiding how that is done are stacked in favor of companies. Employees active in organizing campaigns often are fired or dismissed for pretextual causes, then left with an often years-long legal fight to right the wrong. Fear of getting fired is a palpable thing, and a hurdle for trying to persuade workers to band together to fight for their own interests. The need for strong unions is most pronounced in workplaces where labor abuses are more prevalent, and retaliation more likely. We need much stronger protections and faster decisions — with real penalties for employers — for workers who try to exercise their right to collective bargaining.

But unions also face cultural headwinds. Relatively few people understand labor history and its role in defining the contours of working life even for nonunion workers, including the norms of an eight-hour day and two-day weekend. Shoring up that knowledge could help enhance unions’ image.

Many unions also have largely aligned themselves with liberal political positions beyond labor issues, putting them at odds with a large share of their members. Many also have become contract-negotiating, rules-enforcing mini-bureaucracies (with their own internal turf battles) that can lose sight of the fundamental role of empowering workers themselves. Organized labor needs to do a better job making the case for its own (significant) relevance.

There are ways to improve union support. Under the Ghent system (named for the Belgian city where it began), unions deliver some government work-related services, such as handling unemployment claims and payouts, which gives unions a revenue stream as contractors while enhancing their image among workers. A related concept: economic democracy, expanding corporate and workplace decision-making to include workers and communities with seats for labor on boards of directors. And union-contracted profit-sharing.

Beyond strengthening unionization, our economic system must better address the needs of workers as they lose jobs and seek new ones. Before the pandemic struck, the economy had reached what economists call “full employment,” but that is a misnomer for the slack necessary in the labor market to keep wage growth from overheating. By definition “full employment” means 5 to 6 million people out of work at any given time, a count that does not include the underemployed. Nor does it measure those working at poverty wages.

Clearly we need to explore better approaches, including reviving New Deal-style government jobs programs to provide employment to people working part-time for lack of a full-time opportunity and to those whose jobs have disappeared completely, while also providing a continued connection to working life for those who face long-term unemployment or who have simply given up looking.

Another model: Many states — including California — have adopted “work share” programs patterned after European initiatives in which the government temporarily underwrites lost wages from short-term cuts in paid work hours. That lets companies reduce labor costs during a downturn without the trauma of laying off workers, effectively putting the business into semi-hibernation until things pick up. That’s a good cushion for workers as well as employers, who are then better positioned to weather downturns without the expenses associated with severance packages and the eventual hiring and training of new workers. (Disclosure: The Times used the California work share program to avoid layoffs of NewsGuild-represented employees from mid-May 2020 through late July).

Of course, not all layoffs are temporary. What happens when a layoff becomes permanent — when there is no job to go back to? In a robust sector of the economy, lateral moves are possible. But when an entire industry is crumbling, workers need help transitioning to new careers, something the nation has grappled with — often unsuccessfully — during prior recessions that saw collapses in the steel and auto industries.

We’re seeing something similar happening now in the retail sector as more customers shop online, and in the oil-and-gas sector as future demand for fossil fuels will drop and the need for more renewable energy sources will surge. Retail clerks and oil rig workers tend not to have the skill set to move into, say, building solar or wind farms, a fast-growing sector of the economy. So we need a flexible and reliable system for helping workers transition into a different field of work, such as more robust training and apprenticeship programs.

Many jobs and careers are fluid. The median amount of time workers spent with their current employer before the pandemic was 4.6 years, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but that varied widely by age. For workers between the ages of 55 and 64, the median tenure was 10.1 years; for workers between ages 25 and 34, the median was 2.8 years. Union contracts tend to protect the tenure of longer-serving workers during layoffs, leaving workers who have less tenure, and who often are younger, more at risk for layoff. Younger workers have more time to recover financially from a job loss though they risk derailed career trajectories. Older laid-off workers often have trouble landing a comparable new job at a time in their lives when they should be maximizing earnings and savings for retirement. We need to find ways to both keep younger workers on an upward trajectory and help older workers remain in the work force, while shoring up retirement income options for all.

Will we have the will to make these and other changes? To craft a more supportive safety net for workers and businesses, for more flexibility regarding when and where the work gets done? The pandemic and resulting economic jolt have been disastrous, but also illuminating. We as a society should take this opportunity to improve the way we do things and affix our own silver lining to this particular dark cloud.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.