Editorial: Reaffirm, don’t reverse, landmark Supreme Court libel decisions

President Trump was rightly castigated when he said that libel laws should be changed to make it harder to criticize public figures. Trump’s suggestion wasn’t just self-serving; it smacked of hypocrisy coming from a man who made wild accusations about his critics and political opponents.

But Trump isn’t alone in raising the question of whether the Supreme Court has made it too hard for people whose reputations have been damaged to receive compensation. Some legal scholars have expressed similar concerns. Now two members of the Supreme Court are suggesting that the court revisit a series of decisions stretching back to the 1960s that placed barriers in the way of many libel suits.

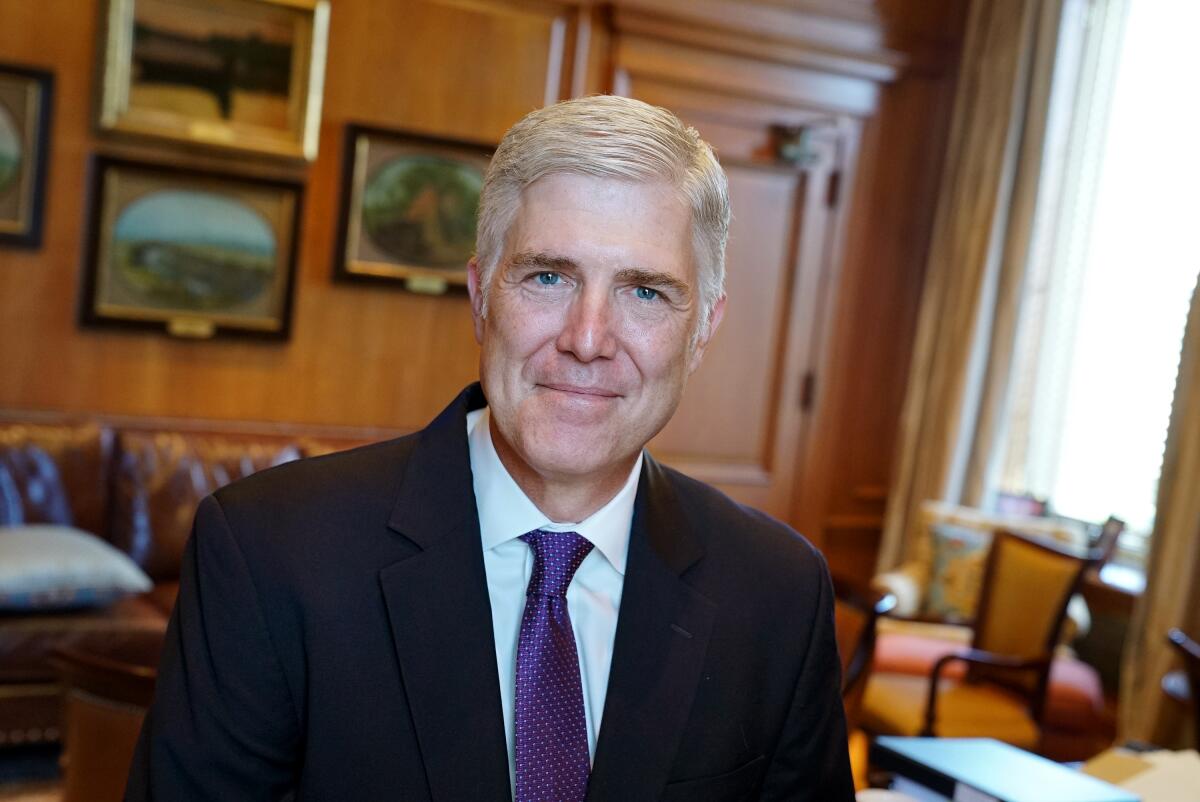

This month, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch dissented from a decision by the court not to hear the appeal of Shkelzen Berisha, the son of a former prime minister of Albania. Berisha had filed a defamation lawsuit against the author and publisher of a book that Berisha said falsely accused him of being part of the “Albanian mafia” and participating in corrupt arms dealing.

The U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a district court’s ruling against Berisha, citing a series of decisions including New York Times vs. Sullivan.

In that landmark 1964 ruling, the Supreme Court overturned a verdict of an Alabama court that the newspaper had libeled a public official in Montgomery by publishing an advertisement placed by civil rights activists that contained some errors of fact. The historical context was crucial: There was a danger that libel trials would be weaponized to prevent accurate news coverage of white racism in the South.

Citing the nation’s commitment to debate on public issues that is “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open,” the court in the Sullivan case laid down a new rule: A public official suing for libel must prove that an article was published with “actual malice” — that is, “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” Actual malice would have to be established by clear and convincing evidence.

Three years later, the court extended the Sullivan decision by holding that not only public officials but also public figures must meet that heavier burden. In his appeal, Berisha argued that the court should reconsider that additional step.

Thomas’ willingness to hear Berisha’s appeal wasn’t a surprise; he criticized New York Times vs. Sullivan in a 2019 opinion. Gorsuch’s dissent was less predictable and also more thoughtful. Echoing a point pressed by Berisha, Gorsuch noted that “private citizens can become ‘public figures’ on social media overnight.” Gorsuch made another point about a “new media world” in which “the deck seems stacked against those with traditional (and expensive) journalistic standards.”

No other justice indicated publicly a willingness to hear Berisha’s appeal. But Gorsuch cited a book review written by Justice Elena Kagan in 1993, long before she joined the court. Kagan noted in the review that some commentators worried that the Sullivan decision, by decreasing libel litigation, might promote false statements. Thus, Kagan wrote, “the legal standard adopted in Sullivan may cut against the very values underlying the decision.”

Admittedly a lot has changed in journalism and communications technology since the 1960s. But none of those changes justifies overruling New York Times vs. Sullivan and subsequent decisions.

Now as in 1964, citizens must feel free to criticize public officials without fear of being subjected to retaliatory lawsuits. Even with the limits imposed by Sullivan (and statutory protections such as California’s anti-SLAPP law), politicians continue to try to take critics to court. Witness the defamation lawsuit Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare) filed against two parody Twitter accounts. Overturning Sullivan could encourage a flood of politically motivated lawsuits by thin-skinned politicians.

It’s also important that the actual-malice rule continue to be applied to “public figures.” Many such individuals (think of Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg) have influence over the lives of Americans greater than that exercised by many elected officials. Like politicians, prominent people — business leaders, activists and entertainers — have ample resources to respond to criticism and correct inaccuracies.

As for Gorsuch’s concern about turning every social media user into a public figure, courts can impose commonsense limits on the definition of “public figure.” An occasional tweet or Facebook post shouldn’t turn a private citizen into a public figure for libel purposes. Nor should a previously obscure individual automatically be treated as a public figure simply because he or she disputes an accusation.

But when citizens take prominent roles in a particular controversy, it’s legitimate to treat them as what the courts call “limited purpose public figures.” That designation is also appropriate when a widely known and well-connected individual capitalizes on that status to rebut allegations. (The 11th Circuit noted that Berisha “did indeed place himself in the public eye regarding the Albanian arms-dealing scandal.”)

New York Times vs. Sullivan was decided at a particular moment in American history, but its essential insight abides: Libel law must not be used to stifle “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” debate about public issues.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.