Column: In defense of long, bug-crushing, Kleenex-box-sized novels

My friend Susan belongs to a book club where the only rule is that the books have to be 200 pages or fewer. I don’t know, because I have never asked, whether that’s because her fellow readers have limited attention spans or they want to minimize the monthly workload or they actually prefer tight, concise stories.

Whichever it is, I’m all for it. Short books are great.

But my enthusiasm turned to defensiveness when I read a curmudgeonly and vaguely disturbing piece in the British magazine the Spectator by a Fleet Street reporter named John Sturgis who didn’t just argue that short books can be excellent but took an outspoken position against long books — the kinds of weighty bug-crushing tomes that, he says, “strain your wrist” when you hold them. The title: “Good Riddance to Long Books.”

Opinion Columnist

Nicholas Goldberg

Nicholas Goldberg served 11 years as editor of the editorial page and is a former editor of the Op-Ed page and Sunday Opinion section.

His reason for writing seemed to be that the judges for this year’s Booker Prize, the U.K.’s most prestigious literary award, had recently nominated a record-thin 116-page novel, “Small Things Like These,” putting “the short in shortlist” — and making Sturgis’ day. (The Booker winner will be announced Monday.)

Sturgis says he’d rather pay twice as much for half as much book. In a brief historical summary, he says it was a step in the right direction when modernism superseded the Victorian era and tossed out “all that David Copperfield kind of crap” (that’s him quoting Holden Caulfield) and novels became more succinct and therefore more readable.

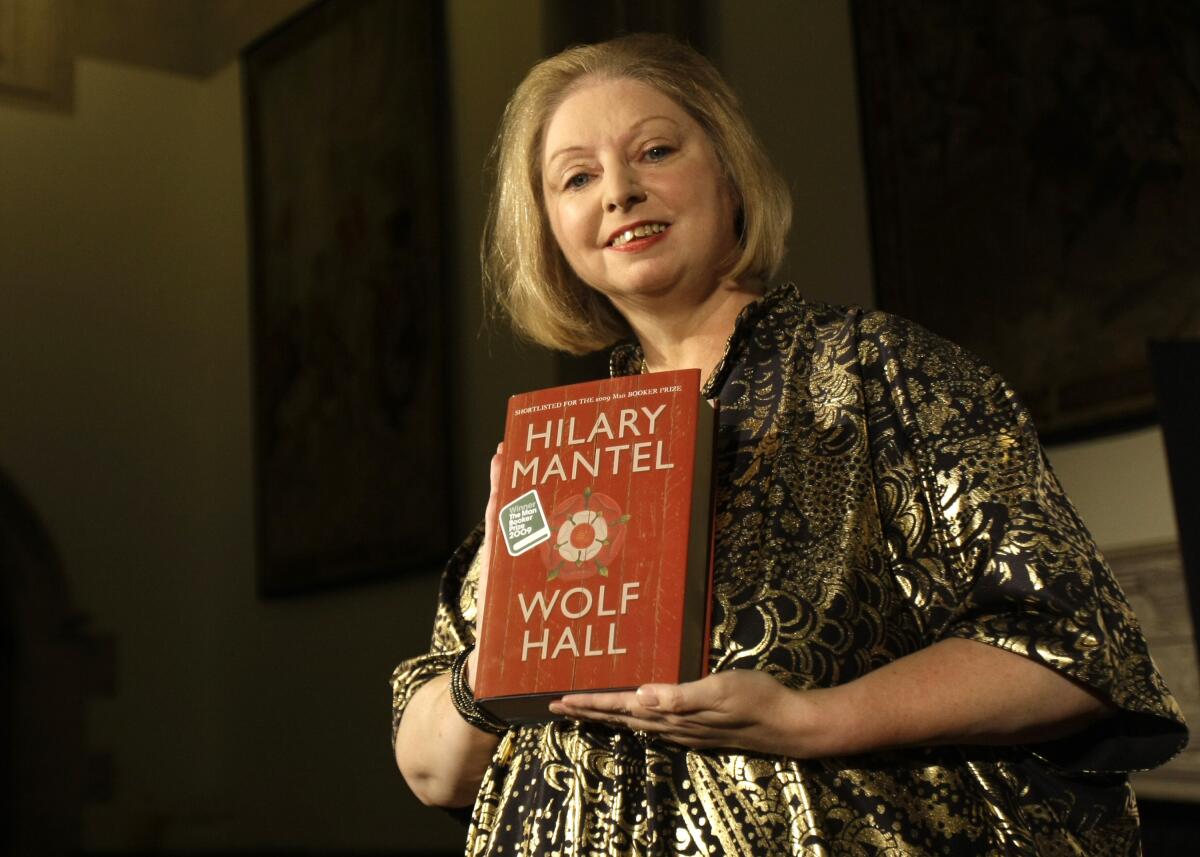

Unfortunately, he says, drugs like LSD — and what he denigrates as “free expression” — tore up the rule book in the 1960s and allowed the way-too-long book to come roaring back into fashion. He complains about Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life,” which he says comes in at 215,000 words (compared to a mere 73,000 for “The Catcher in the Rye”). He complains about “Wolf Hall,” the more than 600-page first volume of Hilary Mantel’s trilogy, and he’s particularly upset by “Lonesome Dove,” a known crowd-pleaser by Larry McMurtry, which at 839 pages, he complains, is nearly “the size of a Kleenex box.”

I’m not sure how he concluded that LSD was to blame for long books. But I can say this: He is apparently not alone in preferring short books.

A nonprofit literary organization called Wordsrated reports that in the last decade, from 2011 to 2021, the average length of books on the New York Times bestseller list (nonfiction and fiction) dropped by 51.5 pages, from 437.5 pages to 386. In 2021, only 38% of bestsellers were longer than 400 pages, a 29.5% decline from 2011.

Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2022 include John le Carré’s ‘Silverview.’ In the Booker Prize longlist, Leila Mottley’s ‘Nightcrawling’ is among the titles.

“Hard times for the thick tome,” as an article in El Pais put it.

The report from Wordsrated apparently reflects the zeitgeist generally, judging from online solicitations such as “Short Books for Busy People” and “20 short novels you can read in one day.” (Uh, all 20 in a single day, or a day for each? A few more words might have clarified that.) There’s also “Eight short novels your book club will actually finish,” and an essay that claims that reading short classics is “the quickest and cheapest way to become ‘well read.’ ”

Okay, I get it. We are all busy people. Who’s got time to lie on the couch eating bonbons for hours and lapping up delicious 1,000-page stories about made-up people in made-up situations while our bosses are Slacking us and the television is beckoning and the real world is falling apart?

But, really, someone needs to speak up for long novels — for the hours of escape they promise, their fuller characters and the worlds they build. For making us more empathetic and forcing us to engage with the ideas of others. For the exercise of our underutilized imaginations and our declining attention spans.

I don’t want to come off as elitist. Don’t think I don’t enjoy action movies or hourlong TV dramas about cops and serial killers. Or short books.

But I grew up up on Victorian classics of the sort that Henry James dismissed as “large, loose, baggy monsters.” If you become engaged in them, you wish they would go on forever. As a child, my father read me Charles Dickens’ “Great Expectations” and Alexandre Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo” and I was devastated and bereft when those stories ended after only a thousand or so pages.

In Claire Keegan’s slim, powerful ‘Small Things Like These,’ a man confronts a Magdalene Laundry, one of Ireland’s abusive homes for ‘fallen women.’

As a teenager I read the three-volume “Lord of the Rings” and a 541-page paperback of the sci-fi classic “Dune,” which was a real wrist-twister. Later I graduated to Thomas Hardy, then George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, William Thackeray and Anthony Trollope. And the Russians, as famous for their length as for their intensity. Sturgis may be right that it’s physically difficult to pick these books up, but emotionally it’s difficult to put them down.

Measuring the length of books isn’t merely a matter of page numbers. The margins and font size make a difference, and even counting words can be misleading because some writers use small ones and others use big ones. Counting characters is probably fairest, but not the easiest.

So there’s disagreement about what is the world’s longest novel. Perhaps it is simplest just to take the Guinness World Records book’s word for it that “In Search of Lost Time,” by Marcel Proust, is the longest, at 9.6 million characters. I haven’t read it.

I’ve had a theory for a long time that American students are trained in high school to dislike great authors because instead of reading their best books, they’re assigned their shortest books. Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” Dickens’ mediocre “Hard Times,” John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men.”

What’s the appropriate length for a book?

Claire Keegan, the author of the short novel on the Booker’s short list, was common-sensical — and characteristically succinct — when people started questioning whether, as the Telegraph put it, “brevity appears to be back in literary fashion.”

“I think something needs to be as long as it needs to be,” she said. I couldn’t agree more.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.