Column: How this young Latinx comic turned harsh, harried Latina moms into comedy gold

Jonathan Chavez can channel your Latina mom better than you.

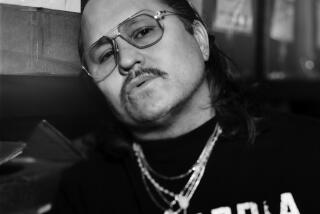

Known as Paqjonathan to his more than 2 million followers across TikTok and Instagram, the 23-year-old Angeleno with bleached pink hair belongs to a growing community of Generation Z Latinos making a living by creating autobiographical digital content.

He became a social media sensation from his mostly Spanish-language Latina mom skits, which resonate with first- and second-generation citizens, often millennials and Gen Xers who see their moms in his comedy. But he’s increasingly making skits in English and featuring younger characters to reach people in his own less bilingual generation.

Opinion Columnist

Jean Guerrero

Jean Guerrero is the author, most recently, of “Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump and the White Nationalist Agenda.”

I met Chavez on a recent rainy Friday in downtown L.A. at Pluma Cafe, where we both wore black faux fur coats by coincidence. I drank café de olla with oat milk; he munched on avocado toast. I’m a millennial, and I wanted to talk about his Latina mom skits, which he told NPR he was ready to move past because they attract older fans and make people mistake him as older. “You all are gonna get in between my dating life,” he joked.

He’s still making those skits, but he wants to branch out, and to be seen as more than a comic. He’s releasing love songs and a podcast.

Racial identity is as personal as it is a product of how we’re seen. But what is obvious to me about my Latino relatives is not how many of them see themselves.

Chavez’s mom skits, inspired by his own mother, are a central way he’s connecting with his bilingual audience, but he’s conflicted about their popularity. “I feel like I’m talking s— about my mom in a way,” he told me. “I feel like I’m offending her or exposing her.”

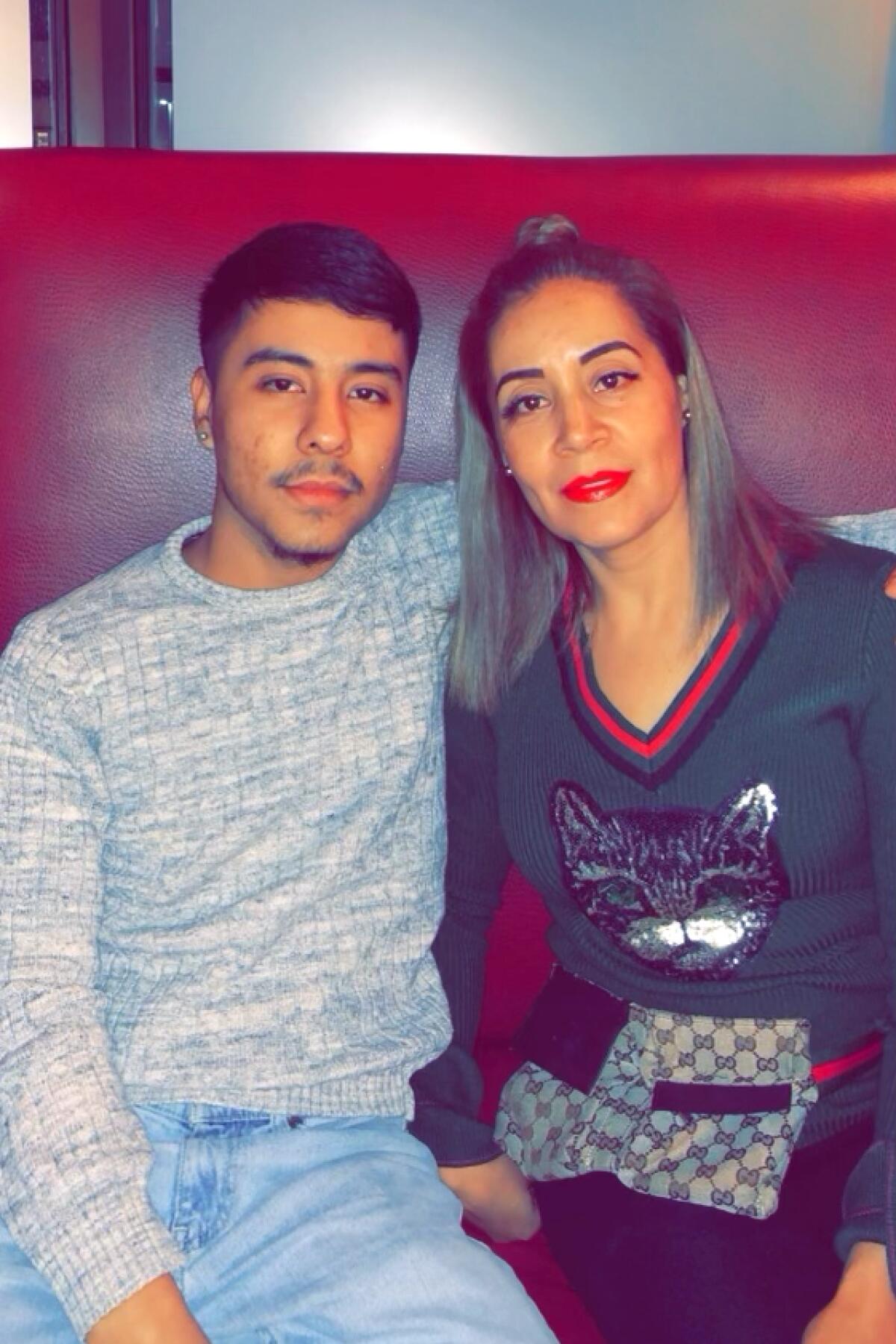

But the humor in his skits works because of his deep affection for his own mom and other matriarchs he knows. Ana Molina, from the rural Mexican state of Chihuahua, raised him and two girls by herself for years, cleaning homes and businesses and working in fast-food restaurants after their dad became an addict. Chavez describes her: “strong, ambitious, and funny. She’s very funny … funny quick.”

Namor, the brown antihero of the film, is no shallow villain. The actor and the character joined forces to send a larger message.

Chavez’s characters are hilarious, but not necessarily caricatures. The conversations, the facial expressions and intonation, the logical contradictions are eerily familiar to Latinos, especially those raised by overworked, frustrated mothers who are trying to keep their kids on track.

In one video, “Latina moms when it gets chilli outside,” he plays a son casually telling his mom he’s going out. He also plays the mom, cleaning in the kitchen. “Put on a sweater. It’s too cold outside, honey,” the mom says in Spanish, an order mixed with sweetness. It escalates. “Put on a sweater. Look, just now I went outside. … It’s so cold, I couldn’t stand it.” The son says he’s not cold. By the end, the mom is yelling, “Put on a sweater! Come back and put on a sweater! It’s cold outside! I’m cold!!!”

In many of his videos, Chavez wears a purple shirt that says “Nadie Me Ayuda En Esta Casa” — Nobody Helps Me in This House. It’s a line from a video in which he plays a mom declining a son’s offer to help clean, only to complain that nobody ever helps her.

Denigrating multilingualism is rooted in the desire to restrict who can belong here. Saying our true names is one way to fight that idea.

Chavez’s mom isn’t his only inspiration. He sometimes crowdsources ideas from fans. And sometimes, the message is painful. “Mexican Abuelas being colorist from day one” was inspired by his grandma’s comments toward him and his mother. It’s among his more popular videos, with 3.8 million views and thousands of commenters sharing similar stories. He channels the hurtful sugariness in which colorism is often coated, saying in Spanish with a smile: “How dark my son is. That’s how I want him: just like that, a dark one, my cutie.”

Demanding mothers who berate their children exist in every color and culture. But Chavez’s nuanced skits can be deeply cathartic for Latinos. When I first found them, I played them again and again, awestruck by this stranger turning my memories into comedy. In comments, thousands of people share identical stories in Spanish and English. “We all had the same mom,” wrote one. “I feel seen,” added another.

During a recent visit to my Puerto Rican mother’s house, I played her Chavez’s videos. We were cuddling on the couch, content on rosé wine after a birthday party I’d organized for her. “Mom, this is you,” I said.

In “Latina moms blaming you for everything that happens,” Chavez, playing a mom, falls with a thud. “I fell because of your fault,” he cries. “Because you’re all looking at me — you knock me down with your gaze. You see I’m carrying this, and you don’t help me! I don’t know what you’re going to do when I die.”

I glanced at my mom. Her eyebrows were scrunched but she was smiling in recognition. At the last line, a trademark of hers, she chortled. “It’s me,” she said.

In some videos, Chavez refers to conduct he once thought of as normal as “traumatizing” since his viewers helped him see certain behaviors — from name-calling to body shaming — as problematic. But he worries he’s maligning his mother.

When I called his mom for her thoughts, she told me she’s proud of him. “I want my children to be happy and for them to do what they’re passionate about,” she told me in Spanish. “Jonathan is happy. I see that he’s happy and I’m happy for him.”

At times, Molina spoke to her children in ways her parents spoke to her. “Times have changed and now we’re more careful about how we say things,” she said. “But I never did it to hurt him, and he doesn’t hurt me with his videos. I see that he does it with a lot of respect, and because we the mothers of our generations are that way.”

On his podcast, Chavez encourages listeners to forgive their flawed mothers. “Go to therapy or try a new hobby, try journaling, try self-care, try speaking to them about it — I know some parents no se prestan para eso,” he says, acknowledging in Spanglish that some are incapable of dialogue. “But try something!” he says with a laugh. “Sure my mom has f— up with me and my siblings, right? I can’t say no, ‘cause I don’t think the perfect parent exists, but if I focus on the bad then I’m just gonna see her for that.”

Chavez started going to therapy last summer, and he’s applying lessons he’s learned with his mother. When she’s agitated, he gently points it out to her and makes empowering statements to her. “I give therapy to my mom,” he told me, laughing.

He added, “The way my mom is, it made me so difficult to communicate with — it made me crazy, a little crazy. If somebody tries to give me advice, those are fighting words, I get defensive right away. But she also made me tougher.”

His complicated feelings come through in his skits, which don’t villainize the mother characters. But he doesn’t glorify any mistreatment either, like one Latino social media comedian who sells merchandise boasting of being raised by “La Chancla,” a flip-flop sometimes thrown by Latina mothers at misbehaving children.

Leslie Priscilla, the author of a forthcoming book about chancla culture, told me she sees Chavez as one of the few social media comedians provoking thoughtful conversation about problematic mothering in Latinx households. “He’s naming that this isn’t normal and that this is traumatic,” she said. She contrasts him with George Lopez, the Mexican American stand-up comedian who in a 2020 Netflix special framed the beating of Latinx children as a virtue. His audience proudly chanted of a child: “F— him up!”

Such content perpetuates false stereotypes of Latinos as uniquely violent. Priscilla, also the founder of Latinx Parenting, told me that healing from intergenerational trauma emerges from recognizing the abuse as wrong while contextualizing it empathetically.

My friend Armida López, an actress and filmmaker from El Salvador, told me Chavez’s videos help her see her mom “in a brighter light.” Her mom often made her kneel on raw rice for hours as punishment when she was a child. “I always thought my mom was the only bad one,” she said. Then she found Chavez’s Instagram. “I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’m not the only one.’ I feel a little better. It’s almost like, we’re all in it together.”

The alchemy of Chavez’s performances is rooted in his childhood: a house full of music, which his mother blasted for comfort as she struggled in a country that wasn’t her own. When Chavez was growing up in Denver, Molina sang along to the Mexican singer Jenni Rivera and regional music. He loved it. By age 5, he’d invite neighbors over to watch him sing songs by Rivera and the Mexican pop group RBD. It felt amazing to perform.

But he didn’t think he could make it in entertainment. He rarely saw brown people on screen. He did well in school and was soon training to become a nurse, posting skits inspired by his mom and friends on social media for fun. Then the videos blew up.

He realized he could become a star — maybe even as big and bright as Rivera someday.

His mother was nervous when Chavez shared his plan to move to L.A. to pursue an alternative path, but she believed in him and the values he’d learned. “He’s a very responsible boy,” she told me. “He never forgets that he has a mother — he always calls me, he tells me everything he does, if he’s happy or sad. Since he was very little, he was very mature.”

Chavez may not want to be seen as wise beyond his years, but it’s a gift his mother gave him. His comedy is a bridge between Latinx generations. He’s a decade younger than me and decades younger than many mothers, but he’s bringing many of us closer together, through laughter instead of the burdens we’ve been carrying.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.