Column: Bad Bunny stays true to himself at Coachella

A dozen rows from Coachella’s main stage, I sat on the grass hugging my knees to my chest as strangers pressed up against me, all awaiting the first Latin music act to ever headline the festival: Bad Bunny.

I was crammed with the Puerto Rican superstar’s most devoted Coachella fans, willing to endure two hours of bodily contortions from the end of the preceding act to the start of his performance for close-up views of Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio. I was having second thoughts about the physical sacrifice, but we were so tightly packed it would have been impossible to escape.

It was my first time at Coachella. I’d always seen the festival as too costly and corporate. But this lineup was interesting to me, the most diverse in its two-decade history, topped by a political icon from my mother’s island. I’d come with two of my best friends; we’d awoken at the campgrounds that morning to a woman loudly mistranslating Bad Bunny’s lyrics.

Opinion Columnist

Jean Guerrero

Jean Guerrero is the author, most recently, of “Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump and the White Nationalist Agenda.”

I was never a fan of reggaeton until I heard Bad Bunny’s political songs. “El Apagón,” about Puerto Rico’s ongoing blackouts and colonial status and about how everybody wants to be Latino but they lack sazón (a spice blend my abuelita always uses), lit a Boricua pride in me, which can be hard to sustain in California, where only 0.6% of people are Puerto Rican and most know little about the U.S. colony.

Like many fans, I was curious to see how political he’d get. There have been rumors that he’s dating Kendall Jenner, who is seen by some people as a queen of cultural appropriation. It fueled speculation that he might abandon anticolonial activism and lose touch with Puerto Rico now that he owns a mansion in L.A. and is a mega-celebrity.

Awaiting his set, I chatted with others in the crowd. One person I met, Vivian Gomez, 37, a Mexican American resident of Orange County, told me Bad Bunny opened her eyes to Puerto Rico’s plight. “I didn’t know there were colonizers taking over and pushing out Puerto Ricans,” she said.

She sees parallels between the displacement shown in his “El Apagón: Aquí Vive Gente” documentary-music video and gentrification in Mexico, where she was born. She hopes Bad Bunny’s artistry inspires people to respect Latin America and its people. “We have a lot more to offer than just bocaditos and tacos and tequila,” she said.

Others around us weren’t as interested in politics. Behind me, Isaac Guerra, 20, a Mexican American in a Bad Bunny T-shirt, told me he’s all about the beat. “It makes you want to just start dancing, you know?” He also likes the singer’s fashion, which defies gender norms. “I wouldn’t normally dress like him, but I think it’s really dope.”

From boygenius’s joyful harmonies to Bad Bunny’s history lesson to Blackpink’s declaration of superstardom, it was a wild and rewarding Coachella.

Bad Bunny has become the world’s most-streamed artist, adored even by non-Spanish speakers because of his catchy rhythms, boundary-blurring authenticity and more. Another fan I talked to was Quincie Onyejekwe, 34, from Nigeria. “I have no idea what he’s saying, but I’m vibing,” she told me. “As he sings, you feel what he’s singing.” He gives her hope for other non-Anglo headliners from across the world. “He’s showing that you can sing in your own language and people can still vibe.”

Around 11:30 p.m., Benito’s voice washed over the crowd, which erupted in ecstasy. In a sultry tone, he gave an ode to Coachella as a place of first kisses, of first getaways, of finding ourselves and the answers to our questions. He reveled in the significance of the moment: the first time a Spanish-language artist has headlined here. “De tantas y tantos, nunca antes hubo uno como yo,” he said, to screams.

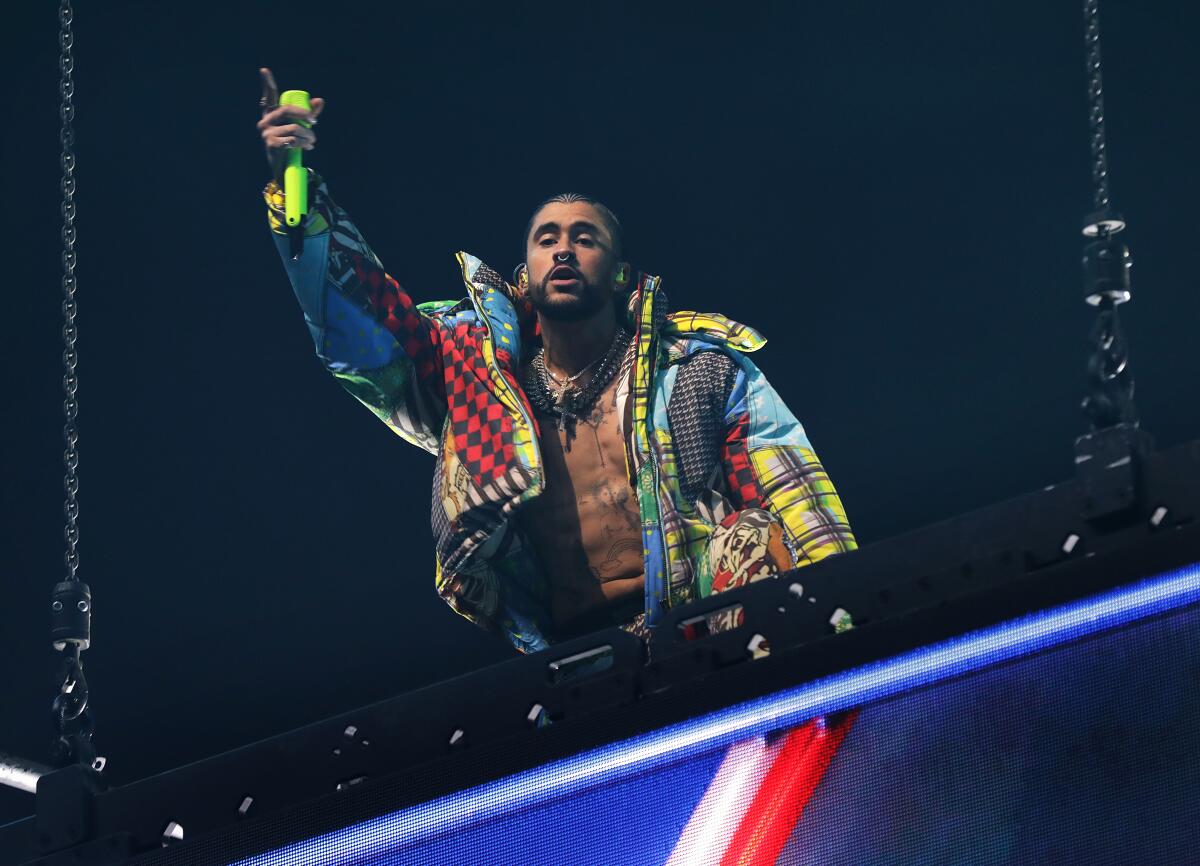

Suddenly he appeared, his luxurious, colorful puffer jacket exposing his tattooed chest. The entire crowd was up dancing, electrified and singing along to “Tití Me Preguntó.” Most people seemed to know every word. A lump formed in my throat as I recalled growing up at the height of English-only nativism and attending a grade school that forbade speaking Spanish, my native language.

Briefly, he spoke English. “I want to know somethin’ before I keep going with me show — with my show.” He paused. “What do you prefer? Me talkin’ in English o hablando en español?” People shrieked: “Español!”

Later, Coachella’s huge screens showed the histories of salsa and reggaeton, born of Black people resisting oppression in the Caribbean. The team consulted with Petra R. Rivera-Rideau, author of “Remixing Reggaetón,” about reggaeton’s history. “I’ve been to a lot of reggaeton concerts in my life and I’ve never seen a video like that,” she told me.

Vanessa Díaz, who teaches a Bad Bunny course at Loyola Marymount University and created a “Bad Bunny Syllabus” with Rivera-Rideau, says the videos show he’s staying true to his roots. “He did that for Puerto Rico,” she said. “He cares about the fact that the performance was being streamed all over the island and every single person in Puerto Rico who saw that was proud and excited and felt represented.”

Eventually during the show, Bad Bunny got vulnerable, saying he was bewildered by stuff he read online. He reassured us that he knew exactly who he was and his purpose, which he swore he’d fulfill: “Sé cual es mi propósito en la tierra y se los juro que lo voy a cumplir.”

What does the Boricua luminary see as his purpose? He didn’t say. Instead, he introduced “El Apagón” as the song that fills him with more pride than anything else in the world. He performed it, and those of us who understood it as the beginning of his answer went wild.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.