Editorial: Should we name heat waves? It’s worth a try to save lives

Not a lot of people know about one of California’s worst disasters in the last few decades, one that overwhelmed hospitals, sent bodies piling up in coroner’s offices and was deadlier than the 1994 Northridge earthquake or the 2018 Camp fire.

That’s what happened when a severe heat wave smothered California in July 2006, killing an estimated 650 people. But it may be tough to recall because unlike hurricanes, wildfires or earthquakes, heat waves don’t typically have names. They are already the deadliest weather-related hazard, and they’re getting worse because of climate change. Yet they remain ill-defined and anonymous threats, silent, invisible killers that few people take seriously until it is too late.

But what if the most life-threatening heat waves did have names? Would people pay more attention to the risks of a heat wave Zoe or Cleon? Could lives be saved?

There is initial evidence it could, as seen in some areas in Europe that have begun categorizing and naming the most severe heat waves based on their threat to people’s lives and health.

The state needs to adopt clearer rules on where it’s risky to build and then make it much easier to build everywhere else.

Under state legislation signed last year, California is now developing a $3-million extreme heat ranking and early warning system to be in place by January 2025 that could include giving names to specific heat waves. In Spain, Seville started piloting a formal system to categorize and name heat waves last summer. This month, Greece and Cyprus adopted the name “Cleon” for one of the region’s worst and longest heat waves on record, and some think tanks, meteorologists and public health experts are pushing for the practice to be replicated and standardized in other communities.

But the World Meteorological Organization opposes naming heat waves on the grounds that it would confuse and distract the public. What works for tropical cyclones may not be appropriate for heat waves because they are not as clearly distinguishable and predictable. And the National Weather Service has no plans to rank or name heat waves either, saying that heat and its health impacts vary so dramatically across different regions and seasons that even coming up with a standard definition of a heat wave is impossible.

But authorities should rethink their stance. There’s nothing to lose by trying out a pilot program to name the most dangerous heat waves, such as the one currently baking much of the United States. It’s pretty clear the current approach to these disasters is falling far short of what’s necessary to protect lives. And because heat is so much less visually arresting than fire, storms or floods, we need other ways to call attention to it and warn the public of the danger.

How can city officials help save lives during heat waves? Make cooling a requirement for habitation, like it is already is for heating during cold weather.

A recently released study found that more than 61,000 people died from heat-related causes in Europe last summer. An estimated 3,900 people in California died of heat-related causes between 2010 and 2019, and the years since have only brought new temperature extremes and deaths.

Death from heat is preventable, and on a warming planet we need bold new messaging to wake people up to its dangers.

This summer, as many experience relentless high temperatures fueled by greenhouse gas pollution and El Niño, there has been new openness to the idea of naming heat waves. People in Southern Europe have dubbed the July heat wave Cerberus, a three-headed dog that guards the underworld in Greek mythology.

Seville’s new system ranks heat waves on a three-tier scale and assigns names to the most dangerous ones working backward from Z to A. The first one to be named under that system was Zoe last summer.

State and local authorities must do more to ensure drinking water is free of PFAS, which are found in many household products, including cookware and cosmetics.

Preliminary results of a survey of more than 2,000 people in Spain found that people who knew last summer’s heat wave was named Zoe were also more likely to take actions to stay safe, including drinking more water, spending more time indoors and warning others about the risk.

Though more research is needed, this suggests that naming heat waves, combined with stronger messaging, can not only help change people’s perception of the risk, but prompt them to take protective action.

It makes intuitive sense that instead of telling people that it’s going to be really hot, it would be more effective to broadcast that Heat Wave Zoe, a dangerous Category 3 event, will start tomorrow and here’s what you can do to protect yourself, your neighbors and co-workers. Names, after all, are easier to remember than numbers or weather forecasts.

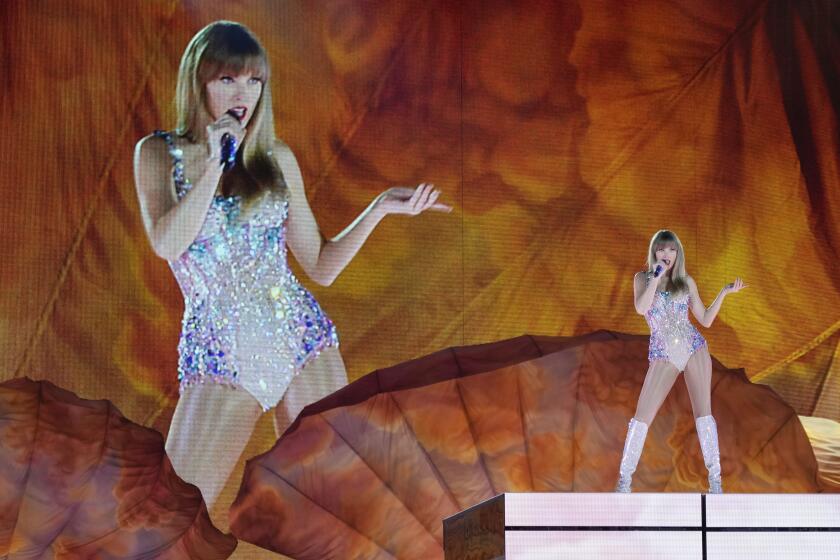

Swifties are fueling a city-by-city transit boom that points the way to reviving slumping ridership by improving service for leisure travelers and non-9-to-5 commuters.

Organizations like the Weather Service and WMO argue that instead of naming heat waves it’s better to focus on strengthening forecasting and warning systems and simplifying public messaging to more clearly convey the danger. Others raise concerns that names could be silly or offensive, such as Beelzebub, and that overdoing them could lead to “alarm fatigue” and desensitize people to the risk.

But if anything, those worries could be best addressed by trusted institutions establishing a standardized ranking and naming system for the highest-risk heat waves instead of it being done ad hoc by media outlets and rogue meteorologists.

A careful design process that includes forecasters, emergency management and risk communication specialists and local officials can anticipate any negative consequences.

And when authorities fail to respond to other types of disasters — think Hurricane Katrina — the name can become a valuable shorthand for accountability. But it’s hard to make progress fighting an enemy with no name.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.