Editorial: California’s strong gun laws need better enforcement. AB 732 could help

- Share via

California law imposes a lifetime ban on any felon (and anyone convicted of specified misdemeanors) from buying, owning, possessing or receiving a gun. Defendants who are not in custody have to turn over their firearms within five days of conviction. It’s one of the nation’s strongest gun restrictions.

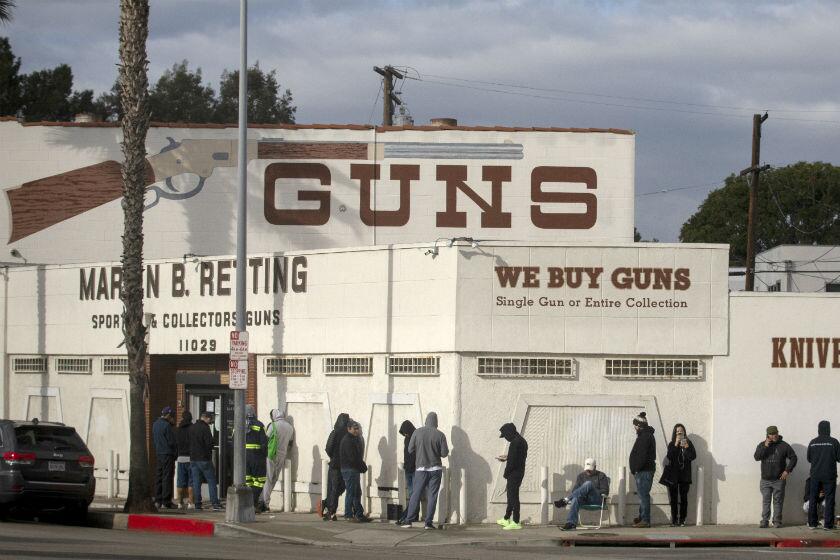

But enforcement is cumbersome and spotty. Courts too often close criminal cases without first confirming that all guns have been relinquished. Every year, about 5,000 names are added to the state’s Armed and Prohibited Persons System, an only-in-California database that cross-references registered gun owners with people who have lost the right to possess firearms because of felony convictions or other restrictions.

The shooting that left six people dead and 12 injured in Sacramento over the weekend was one of more than 120 mass shootings so far this year in the United States. What will it take to stop the slaughter?

That means thousands of people who once lawfully possessed guns but are no longer authorized to have them still do.

Assembly Bill 732 by Assemblymember Mike Fong (D-Alhambra) would tighten the process in part by shortening the deadline to 48 hours for people convicted of felonies and qualifying misdemeanors to give up their firearms. More importantly, it would block judges from closing their criminal cases, even after convictions, until the firearms are turned over. Judges like to close their cases and move through their dockets, so they’d be a lot more likely to give the relinquishment portion of criminal proceedings their full attention.

We may not know the motive for the Monterey Park attack amid Lunar New Year festivities, but we know how the mass killer committed his act: He had a gun.

It is no coincidence that Fong’s district includes Monterey Park, which on Jan. 21 saw the deadliest shooting rampage in Los Angeles County history. A gunman killed 11 people and injured nine others before killing himself. The gun he used was already illegal under California law. But like other firearms restrictions, this one is motivated by high-profile gun violence and is intended to help curb it in other situations.

California’s gun mortality rate used to be about average but now is among the nation’s lowest, thanks in large part to a mosaic of laws that restrict firearm access by people presumed dangerous. Fong’s bill, now in the Senate, would be one such law.

California must do more to stop dangerous people from having guns. It’s shameful that California essentially relies on an honor system asking domestic abusers to relinquish their weapons.

There is disagreement over whether the felon-in-possession ban would be embraced or rejected if it ever comes before the U.S. Supreme Court. The court’s opinions have expressed an increasingly expansive interpretation of the 2nd Amendment right to keep and bear arms.

In District of Columbia vs. Heller in 2008, the court ruled that Americans have a right to guns for self-defense in their homes, but the opinion included this often-cited line that appears to favor California firearm relinquishment laws — “nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill.”

Shooting deaths in places once reserved for celebration are now as American as apple pie and Fourth-of-July parades

Things are less clear after last year’s ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn. vs. Bruen, which struck down a New York law requiring a person to show a special need before being granted a license to carry a concealed weapon. The court in Bruen said constitutionality of a gun restriction turns on whether it’s “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

The court will soon consider whether to overturn laws that restrict gun possession by people who are clearly dangerous although not convicted, and those convicted but not necessarily dangerous. California has laws in both categories.

The meaning of the “right to keep and bear arms” has been disputed even since before the 2nd Amendment was drafted. The Supreme Court won’t settle the question, but its search for compromise can quiet the argument for another decade — or bring disaster.

Quite alarmingly, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in February struck down a Texas law that requires people to give up their guns when a domestic violence restraining order is issued against them. The plaintiff in U.S. vs. Rahimi was not (yet) convicted of a felony but was obviously dangerous, with a documented history of injuring his girlfriend and firing his gun in anger at others.

Yet, the court reasoned, the U.S. had no domestic violence restraining orders when the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791, so under the Bruen decision, the ban violates the 2nd Amendment. The Supreme Court has accepted the case for review.

Perhaps it’s the fate of the United States to watch its soul die along with the 19 students and two adults shot to death Tuesday at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

Then in June, the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Range vs. Attorney General that a federal felon-in-possession ban cannot constitutionally apply to a person convicted of a nonviolent crime in Pennsylvania.

Not only were there no such bans against nonviolent convicts in the 18th century, the majority wrote, but there were no lifetime bans even against violent felons who had served their sentences and returned to their communities. That case too may appear before the Supreme Court.

The decision striking down a New York law that restricts who can carry a concealed handgun could doom some of California’s smart gun safety laws.

Fong’s bill does not create a new felon-in-possession ban. It simply makes an existing California law easier to enforce. The Senate should pass it when it returns from its recess next week even though the law it supports may be in jeopardy.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.