Opinion: How to prevent Black kids from becoming stuck in foster care

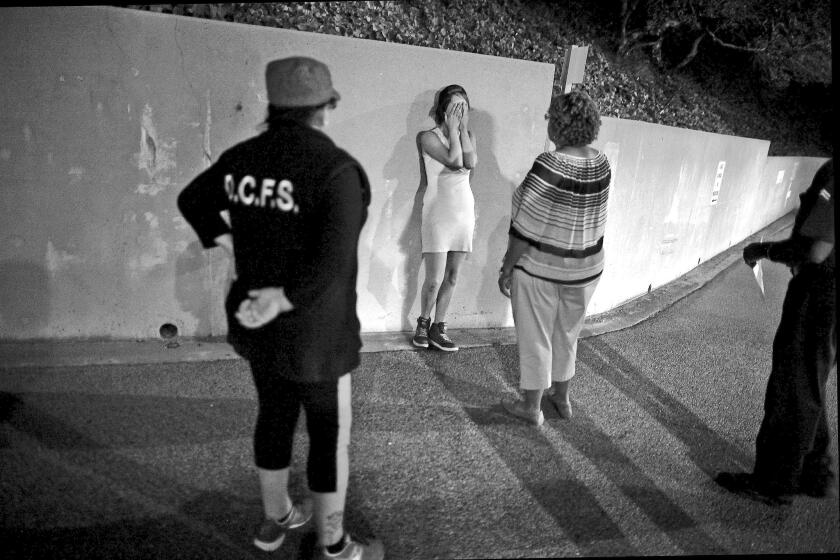

All foster children deserve a chance at finding their forever families. Far too often, Black and brown children remain in foster care too long without needed support. State and federal leaders can change that.

In the 15 years I served as a caseworker in impoverished communities in New York City and the Bay Area, most of my cases were Black or brown children. On average, Black children spend longer in foster care than white children. Black youth are also more likely than white youth to age out of foster care without a family.

A disproportionate number of Black children are removed from their homes in L.A. County. Now, the county has backed a “blind removal” pilot for study.

Despite caring social workers and extended families trying their best to help, these youth often grow up in a system that cannot meet their needs. And their needs are considerable: Kids from low-income neighborhoods, especially Black kids, experience higher levels of trauma and the effects of systemic racism. A systemic response can address that.

Many Black children in foster care are placed with families of a different race who may not be adequately trained, educated or supported to handle the unique challenges Black children face. This has been a challenge for the child welfare system — one that requires prioritizing equity-based solutions and preparing foster families to address these challenges. For instance, Black parents in the U.S. often have conversations with their children about the ever-present threat of racially biased police violence. White foster parents, who may not have had similar life experiences, can still raise Black children to be aware of the risk, with education and support.

For me, a mixed-race child, my ties to racial identity were severed when I entered the foster system unaware of the ethnicities that made my brown skin.

It is no wonder that emerging evidence suggests Black Americans are more skeptical of the benefits of the foster care system. A new Kidsave-Gallup study found that 71% of Black adults agree that the foster care system could do more to help biological families stay together, compared with 65% of Hispanic and 55% of white adults. Black adults also are the least likely to agree that the foster care system supports children in need of care.

The data also point to part of the solution, however: More than one-third of Black Americans reported having thought a lot about providing foster care (34%) or adopting from foster care (26%), above national averages. A few simple changes could remove obstacles that some of those Black families face so more of them can foster or adopt Black children.

Her entrance caused a stir.

One initial hurdle is to change perceptions within Black communities about the child welfare system. Educational campaigns focused on positive representation would be a start. Families who do not meet the income and housing eligibility requirements, including Black families, are excluded from fostering and adopting, but federal and state legislation could provide waivers for placements to make up for small shortfalls and ensure administrative support is provided for applications and other paperwork. Anti-discrimination laws and enforcement are also needed to ensure that applicant families are evaluated without racial or implicit bias.

State and federal governments should be investing in recruitment in Black communities to find and encourage potential foster parents and support those who get involved, particularly by providing further administrative support and free and affordable mental health services, so both parents and children are well supported.

Foster and adoptive families and mentors of any race would also benefit from peer support, and the child welfare system should facilitate those connections. Formal education within the system could increase cultural competency among non-Black families who are fostering or adopting Black children. For example, parents may need to learn how to properly care for Black children’s hair. This is the kind of knowledge that families and Black children in foster care need to thrive together.

At the policy level, some federal changes could help all children in foster care. President Biden’s Proclamation on National Adoption Month last fall highlighted positive steps forward that could encourage more families to adopt, such as pushing for a fully refundable adoption tax credit. He also hopes to expand the Military Parental Leave Program, which would support families who adopt by offering 12 weeks of nonchargeable, paid parental leave to service members who give birth, adopt or provide long-term foster care. And the White House has called for housing vouchers to help keep children off the streets when they age out of the foster care system.

To truly reform the child welfare system, we must not only help children now in care but also reform the systems that have led to the disproportionate representation of Black children at risk of remaining in foster care until adulthood. This would include a wide array of funding and policies that would support biological families that are trying to stay together, such as continuous postpartum coverage for low-income women and reduction of child protective services intervention in cases of neglect due to poverty, to best ensure that these children and their families can succeed.

Shantay Armstrong leads Kidsave’s EMBRACE Project, an initiative aimed at improving outcomes for Black youth in foster care.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.