A history of Yellowstone finds centuries of conflict behind the natural beauty

Book Review

A Place Called Yellowstone: The Epic History of the World’s First National Park

By Randall K. Wilson

Counterpoint: 432 pages, $34

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The English language falls short when trying to describe anything epic. Randall K. Wilson, a professor at Gettysburg College, faces that daunting task in describing the cataclysm that created the caldera in which Yellowstone National Park sits. The first volcanic eruption occurred 2.1 million years ago and “released about 600 cubic miles of debris … roughly 2,400 times the amount of debris from the eruption of Mt. St. Helens in 1980.” The blast obliterated nearby mountains, including part of the Tetons range. Two more eruptions of similar size contorted the landscape, creating domes and depressions and vents for the boiling earth below it.

The more recent history of how the park came to be isn’t quite so cinematic, but Wilson’s talent as a storyteller shines through in turning dry bureaucratic bumbling and crony corruption into a focus on individual exploits and entertaining tales. It makes for great reading.

He argues convincingly that the force of capitalism’s drive to exploit the American West, including the building of railroads that would make Yellowstone more accessible, was soon met by a developing ethos of those who wanted to preserve Yellowstone’s wonders and protect them as a national treasure for “all” Americans — a concept that shifted over time and is still evolving. He writes that the history of Yellowstone is the history of America. The initial attitude by the white majority that nature was a commodity to be exploited evolved into the view that wildness needed to be conserved and protected.

‘Becoming Little Shell’ is the story of one man discovering his heritage, but along the way he sees how so many others have been dispossessed in so many ways.

Sometime between 1805 and 1809, one of the members of the Lewis and Clark expedition sent to survey the Louisiana Purchase, John Colter, became the first Euro-American man to set foot in the Yellowstone area. Wilson uses near-contemporary accounts of Colter’s exploits, along with secondary sources, to spin the type of wilderness tales that have long thrilled readers. Much of the first half of the book combines these firsthand anecdotes with the detailed 19th century history that preceded the park’s founding.

One of the drawbacks of such an approach is its centering of white voices. Wilson makes great effort to include history of the Indigenous people whose presence can be traced back 13,000 years, noting that 27 tribal nations “view Yellowstone as part of their ancient homeland.” And, as he establishes very early, Western notions of “untouched wilderness” actually ignored and erased centuries of continuous habitation.

‘The Mighty Red’ portrays heartbreak past and present for Native Americans and others in North Dakota’s Red River Valley, but author Louise Erdrich finds hope in the landscape as well.

Despite a chapter on the horrendous treatment the Nez Perce received as they were forcibly removed from their lands, his obvious respect for the tribal nations keeps getting undercut by his choice of material. By leavening his exposition with individual accounts, Wilson inevitably amplifies the voices of white explorers and settlers who told blood-curdling accounts of encounters with American Indians, portraying them as murderous. The slaughter of entire villages is summarized in brief sentences that do nothing to convey the scale of their horror. The dearth of Native primary sources, included only in a chapter on bison, creates lacunae where vital histories should be.

The most egregious example is contained in a chapter where Wilson notes that one of the “first conservationists” to advocate for the park was Gen. Philip Sheridan. He reports that Sheridan complained that poachers were rapidly diminishing the wild game when he urged the federal government to protect Yellowstone’s natural wonders. This is the same Sheridan who conducted a campaign of total warfare against Great Plains tribes, including nighttime surprise attacks that slaughtered sleeping civilians. Wilson recounts eloquently the killing of the last herds of wild bison, in 1883, but he fails to mention that efforts to exterminate bison — and starve tribes that depended on them — were another strategy of that same Philip Sheridan.

The second half of “A Place Called Yellowstone” really shines. Here Wilson’s role as an environmental historian makes him an incisive narrator as he follows sequences of events after the opening of the park in 1872. Almost from the beginning, romanticized notions of what constituted “wilderness” were constantly in conflict with the objectives of making Yellowstone into a tourist destination.

Fascinating chapters give readers insight into conservation policies that restored elk and bison populations, in part by exterminating wolves. This proved to be shortsighted, as losing the ecosystem’s keystone predator led to overpopulation and catastrophic die-offs that wiped out thousands of protected animals. Even today, Yellowstone continues to struggle with tourists who want some kind of “full wilderness” experience that includes getting too close to wild animals.

Wilson excels in laying out the sharp political divides that define the contemporary West. From the beginning, he highlights how the geographical distance from the nation’s capital exacerbated discourse that pitted an “incompetent” federal government against local jurisdictions. Attempts by the government to expand wilderness protections to lands near the park erupted into all-too-familiar fights against “federal land grabs.”

Wilson notes sardonically that ranchers, whose identity is built on notions of rugged individualism, welcome infusions of federal tax dollars through infrastructure development or mining and agriculture subsidies. In one of the more comic illustrations of the hypocrisy, Wilson tells the story of Hollywood actor Wallace Beery, who was hired to dress up as a cowboy and lead heavily armed protesters who drove 550 cattle across the newly designated Jackson Hole National Monument.

These same conflicts dog environmental efforts to restore balance to the park. In fights over wolves and bison, sport hunters and ranchers marshal false data to argue that both animals present huge threats to their businesses. Further conflicts arose from the 1988 fires that burned 1.4 million acres in the park, creating public outrage over “mismanagement” with little understanding of the role that conflagrations play in healthy forest ecosystems.

Yellowstone National Park is a place where spectacular waterfalls and geysers astound visitors, a place where herds of bison and elk, along with black bears and wolves, roam. It also has been, and remains, heavily contested ground. Wilson has given us a history of this 200-year ideological war, and there is a lot to admire in his project.

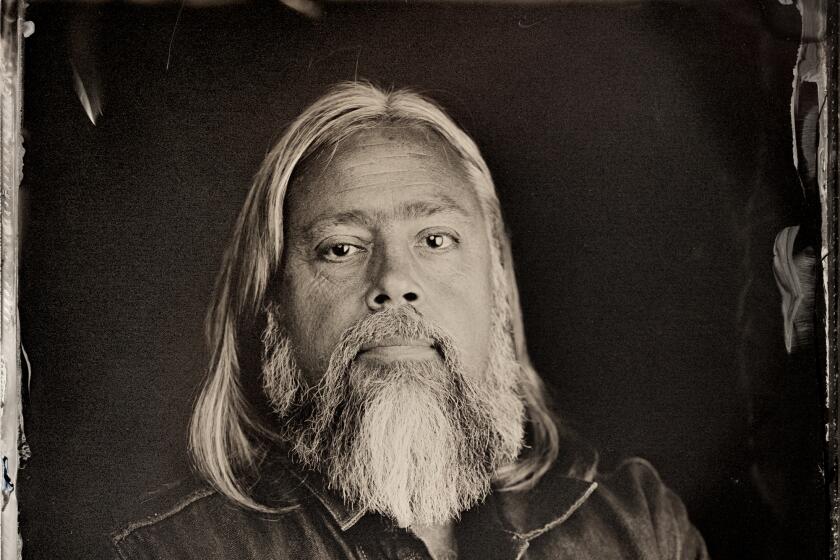

Lorraine Berry is a writer and critic living in Oregon.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.