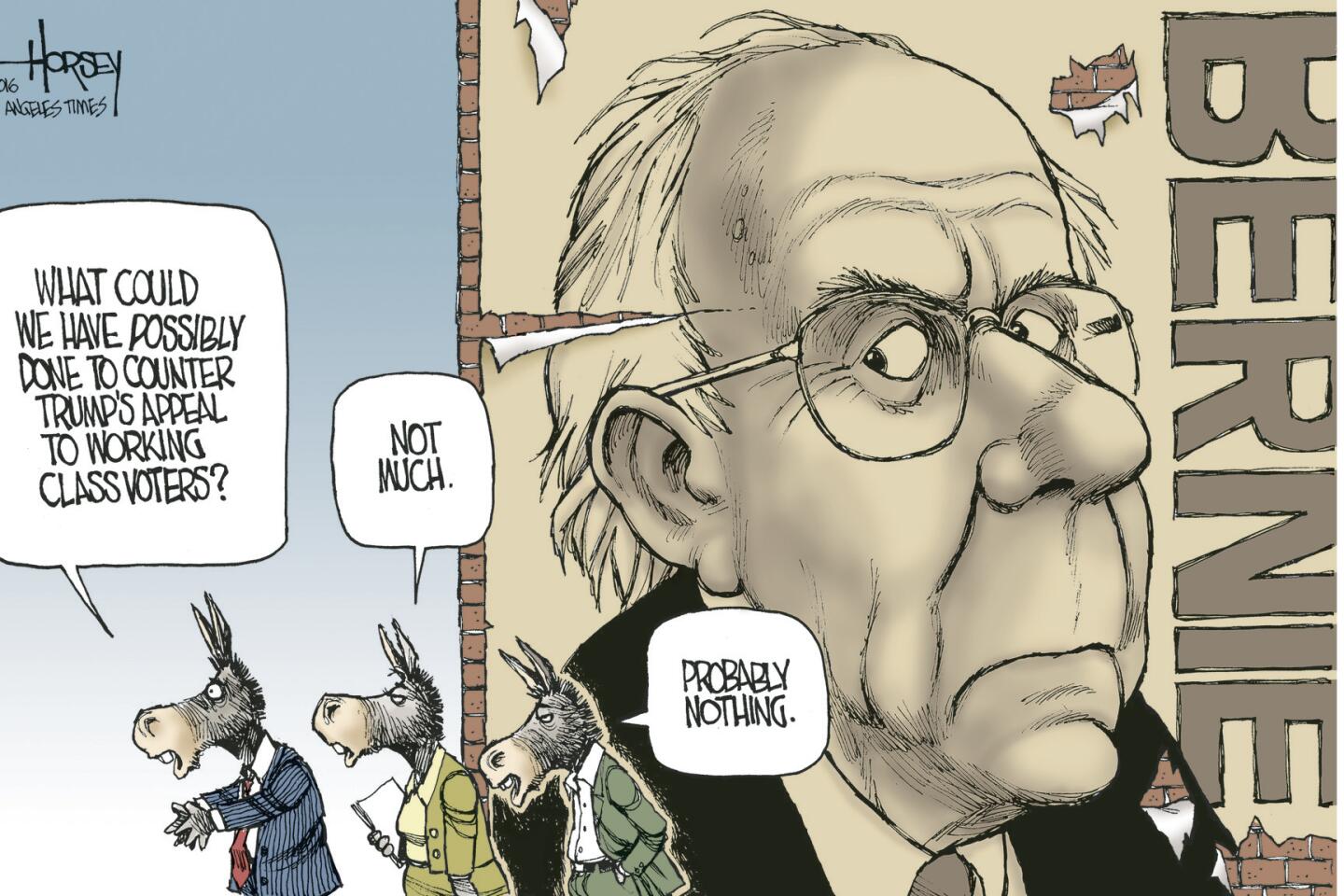

Bernie Sanders’ sober social activism wins him fans in California

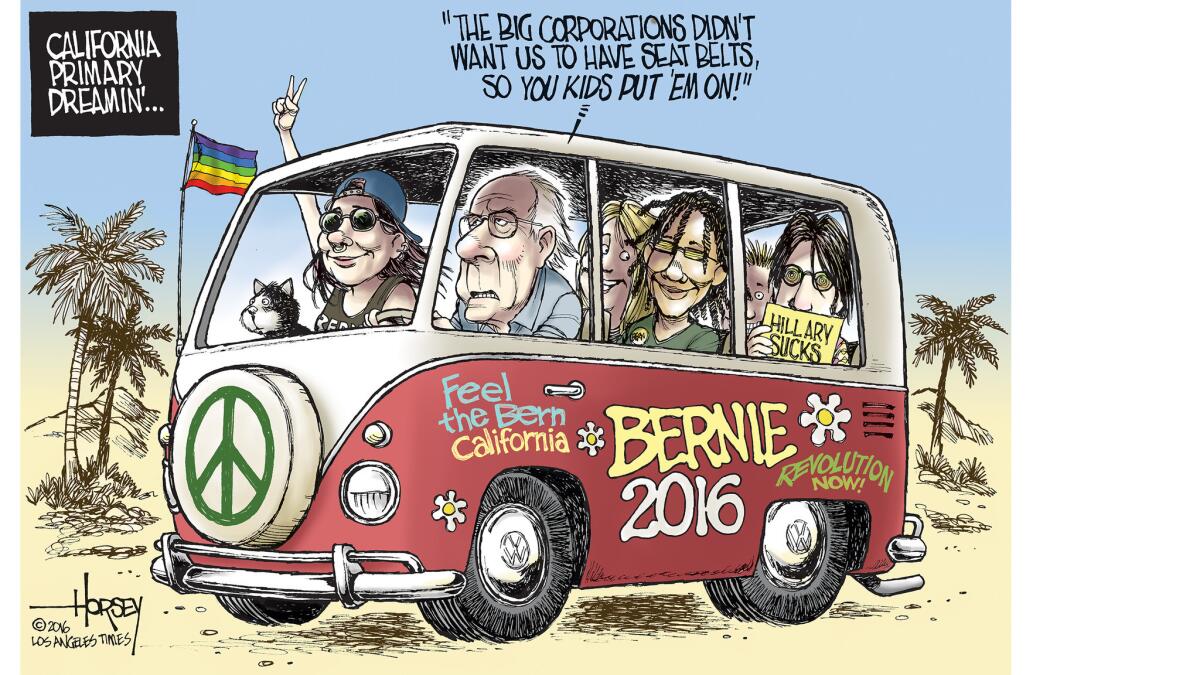

When Lyndon Baines Johnson was Bernie Sanders’ age, he’d been dead 10 years. Unlike LBJ, Bernie is still very much alive, leading a campaign caravan through California and aiming to take his left-wing children’s crusade all the way to the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia the last week of July.

I caught up with Sanders at two rallies — one at a high school football stadium in Pomona on Thursday, the other on Saturday evening at the county fairgrounds in Bakersfield, the city represented by House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, a Republican whose politics are far to the right of Sanders.

The crowds at both events were largely young, heavily Latino and predominantly working class. In both places, Sanders delivered the same speech — the same one he has given in every corner of America — with no need for a teleprompter. It is the consistent content of that message and the way he delivers it that has made him a completely unanticipated force in this campaign.

A year ago, only a few dreamy progressives would have predicted that the septuagenarian democratic socialist senator from out-of-the-way Vermont would become the leader of a youth movement that would seriously disrupt Hillary Clinton’s smooth path to the Democratic nomination. Sanders’ rise to the top tier in the 2016 campaign is, arguably, even more of a surprise than Donald Trump’s success. Trump already had huge notoriety, billions of dollars, easy media access and a fractured field of competitors. Bernie Sanders had nothing but ideas.

I spoke with a college-age woman waiting in line at the Bakersfield fairgrounds. She wore a reversed baseball cap over her long, magenta-tinted hair, jeans ripped at the knees and a black muscle shirt touting “Bernie for President.” Her name was Cela Ayres. I asked her why this rumpled old guy with unruly white hair had become such a political phenomenon among millennials. Ayres said that other candidates — Hillary Clinton in particular — try to connect with young voters by awkwardly “relating” and using gimmicks like Snapchat.

“Bernie just says what relates to us,” Ayres told me. “He doesn’t try to relate to us, he gets us.”

I heard similar sentiments from many in the Sanders crowds. They like his ideas and, even more, they like that he has been pushing the same core ideas since he was a college kid in the 1960s. He may not have charisma, but Bernie has something that seems far more effective this year, especially with young people and older voters who have been disillusioned by too many obsequious, perfectly groomed, cookie cutter candidates (think John Edwards in 2008). Sanders is unquestionably authentic.

If the most dispiriting aspect of the presidential campaign has been the success Trump has achieved with his narcissistic, bullying, dumbed-down rants, a hopeful, positive development is that so many people still have the attention span to sit through Sanders’ very sober, policy-driven lectures. He ticks off his positions like an organizer in a union hall. He very rarely smiles or wastes time with a joke. He doesn’t try to “humanize” himself with soft personal stories. Most important, he doesn’t talk down to his crowd. And they respond with cheers.

Before the mass rally in Bakersfield, I was at a more intimate gathering inside a hall on the fairgrounds where Sanders met with activists, leaders and average citizens from the local Latino community. He was there mostly to listen and gather information. One middle-aged man broke down in tears describing how his father had toiled “forever” as a farm worker, inspiring him to strive higher. Another man talked about getting paid $1.25 to pick a box of strawberries that sells for $40 on the market. Several people complained about the undrinkable tap water in their homes — water contaminated by agricultural chemicals and oil fracking operations. Many others described serious illnesses caused by pesticides sprayed across the fields where their families work.

When Sanders had arrived, he looked sunburned and weary, but the people’s stories roused him. He responded with sympathy and offered remedies that veered a bit too predictably toward his anti-corporate talking points. “If someone came in here and hit someone with a baseball bat, they’d be arrested,” Sanders said. “If somebody is poisoning the children [with pesticides], that person should be indicted, as well.”

I have to fault Sanders for one gratuitous media-bashing comment. While condemning big corporations for the pollution of drinking water in the Central Valley, he scolded the “corporate media” for not telling that story. The Times, in fact, has done in-depth reporting on the subject over several years. But Bernie is a creature of the progressive movement that clings to a wildly simplistic “corporate media” meme. At 74, he probably will not change.

Many of the people who run for president act as if they’ve been planning their campaigns since high school (think Ted Cruz and Martin O’Malley). They tailor their message around what will make them most electable (think Marco Rubio and Scott Walker). They struggle to project an image that researchers tell them will be appealing to voters (think Hillary Clinton and a host of others). Bernie is definitely different. He is as much community organizer as politician. Certainly, he is not a man without ambitions, but he came to the idea of running for president very late. He appears to be doing it as simply the latest avenue of his social activism.

That difference is what has won him an unexpectedly big and passionate following. It is also the thing Democratic leaders who wish he would quit before he gets to Philadelphia simply do not understand. For Bernie, this isn’t politics, this is revolution.

MORE FROM OPINION

White kids, rap lyrics and the question of racism

Reforming the police disciplinary system should be done in public view, not in backroom negotiations

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.