At a South Dakota rodeo, America’s political divisions feel like a passing storm

My new friend, Jim, spent 15 years as a coyote trapper working out of an abandoned cabin in the wilds of North Dakota until federal marshals showed up and ordered him to move on. Now Jim lives a less solitary life with his wife, Heidi, on a ranch near tiny Whitewood, S.D.

That’s where I met Jim, thanks to mutual friends, last Saturday night. We sat out on his deck in the warm twilight, drank beer and got acquainted. Jim told me he doesn’t pay much attention to politics, but I got the impression he’s the kind of man who prefers the least government possible (maybe it has to do with those federal marshals displaying their guns as they ended his trapping career). Then, in one of those surprising moments of serendipity, we discovered we had two unique angles on a certain famous political event.

Back in the summer of 1980, Jim told me, he was nearing the end of a solo canoe trip down the Yellowstone River. He had a radio with him and tuned into Teddy Kennedy’s stirring concession speech at the Democratic National Convention in New York City. Amazed by the coincidence, I told Jim that I had been in that convention hall and saw Kennedy deliver his address. I noted that the speech is considered the best of Kennedy’s career, and Jim said Teddy’s oratory had deeply impressed him.

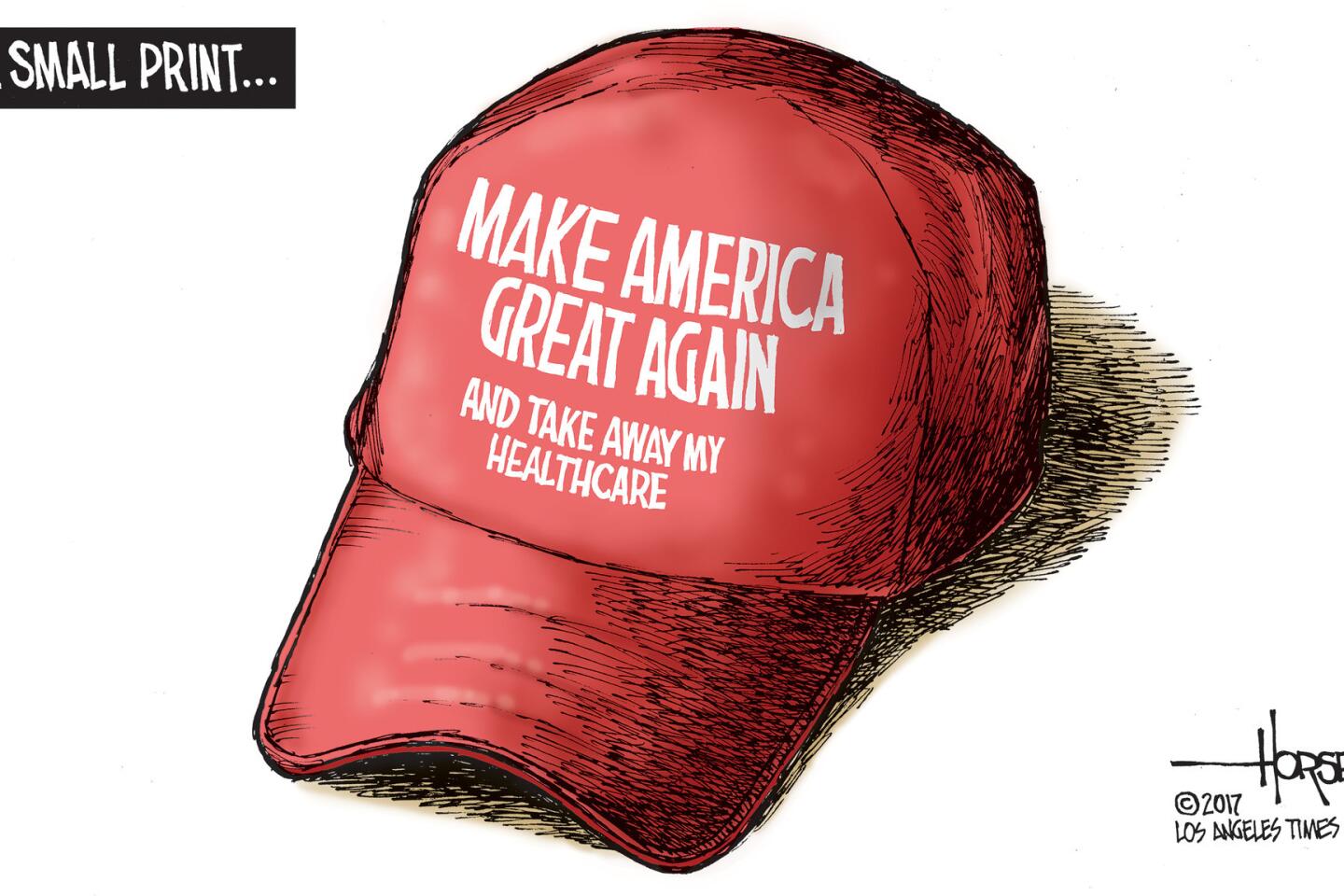

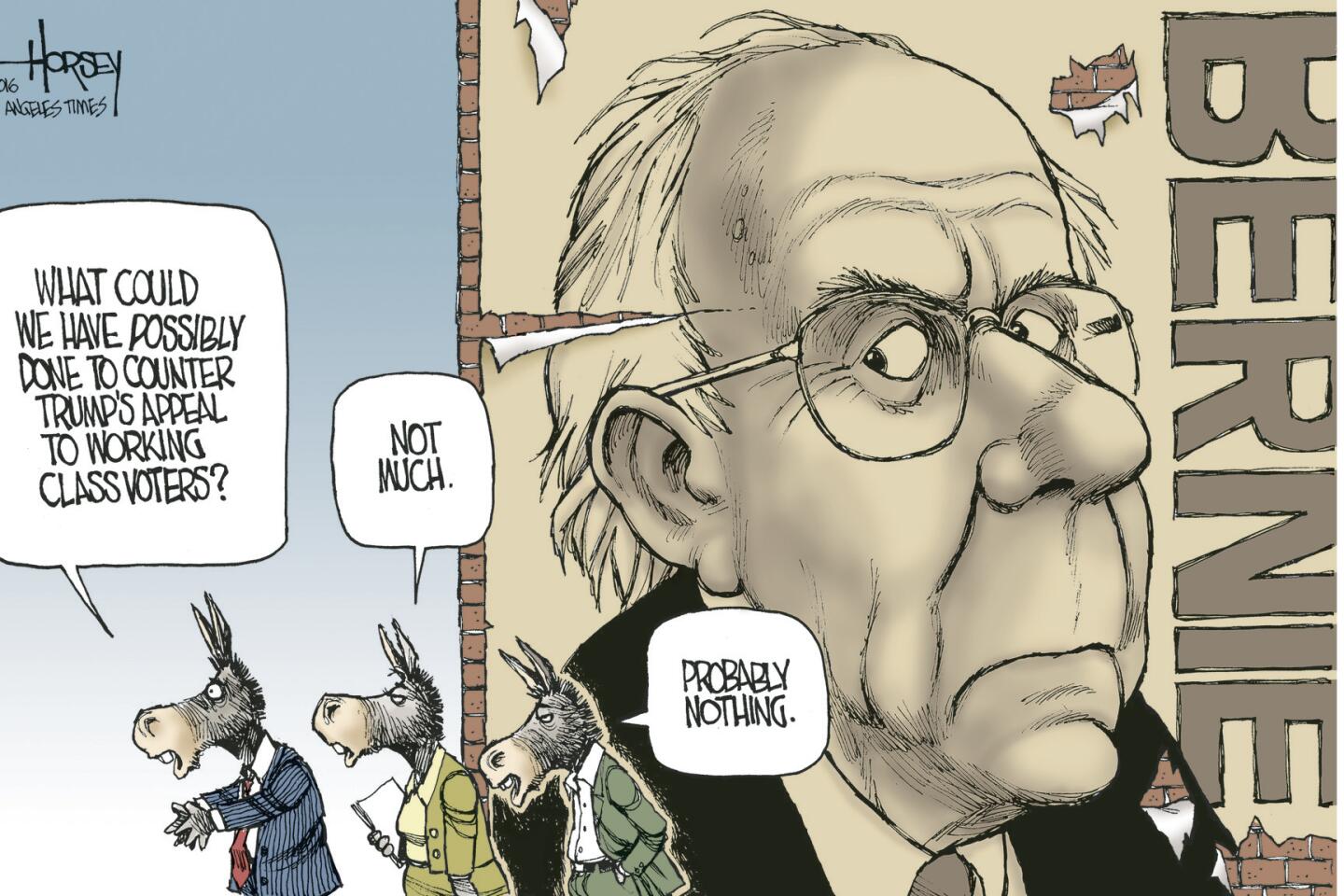

That is an opinion that could get Jim in trouble with some folks in his part of the United States. During a long Fourth of July weekend spent in several towns near the Black Hills, I got the distinct impression that it is easier to come out as gay than to confess to being a Democrat in South Dakota. Folks would draw me aside when they learned about my political cartoonist job and whisper their dislike of Donald Trump. That is a minority opinion in the rural West, where Trump is well regarded and fans of Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders definitely feel like a minority.

A Republican in San Francisco or Seattle would feel just as isolated, of course. In recent decades, Americans have segregated themselves geographically in ways that, more often than not, reflect their political views. If a person tells you where he lives, there is a better than even chance you can correctly guess how he votes.

In past generations, this was much less the case. In the days of Franklin Roosevelt, there were plenty of rural people who became Democrats because the government stepped in to rescue them from economic ruin. And it’s worth remembering that George McGovern, the antiwar Democrat who was crushed by Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election, was a senator from South Dakota. It will be a long time now before South Dakotans send another Democrat to Washington, just as it may be even longer before Californians elect a Republican senator or governor.

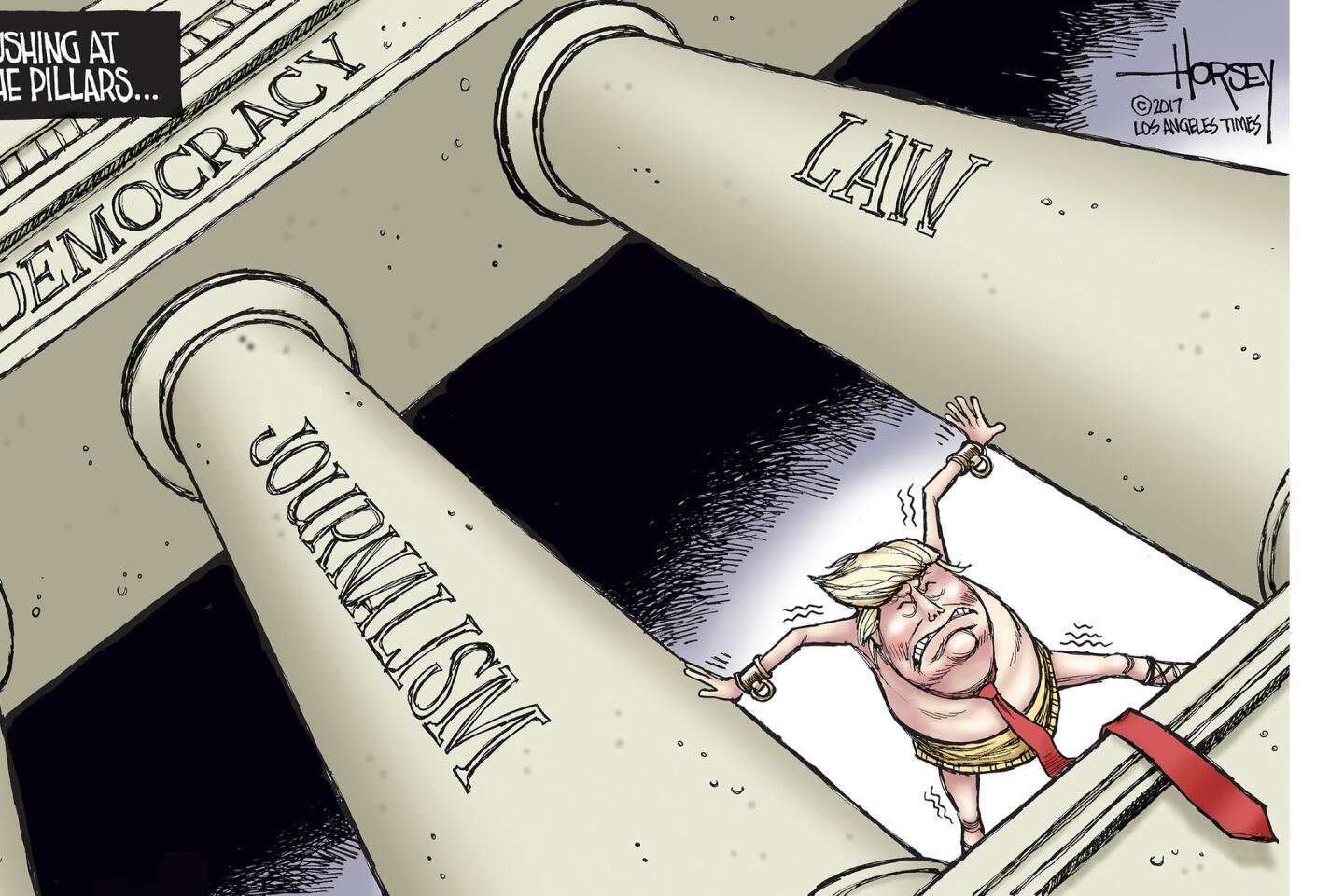

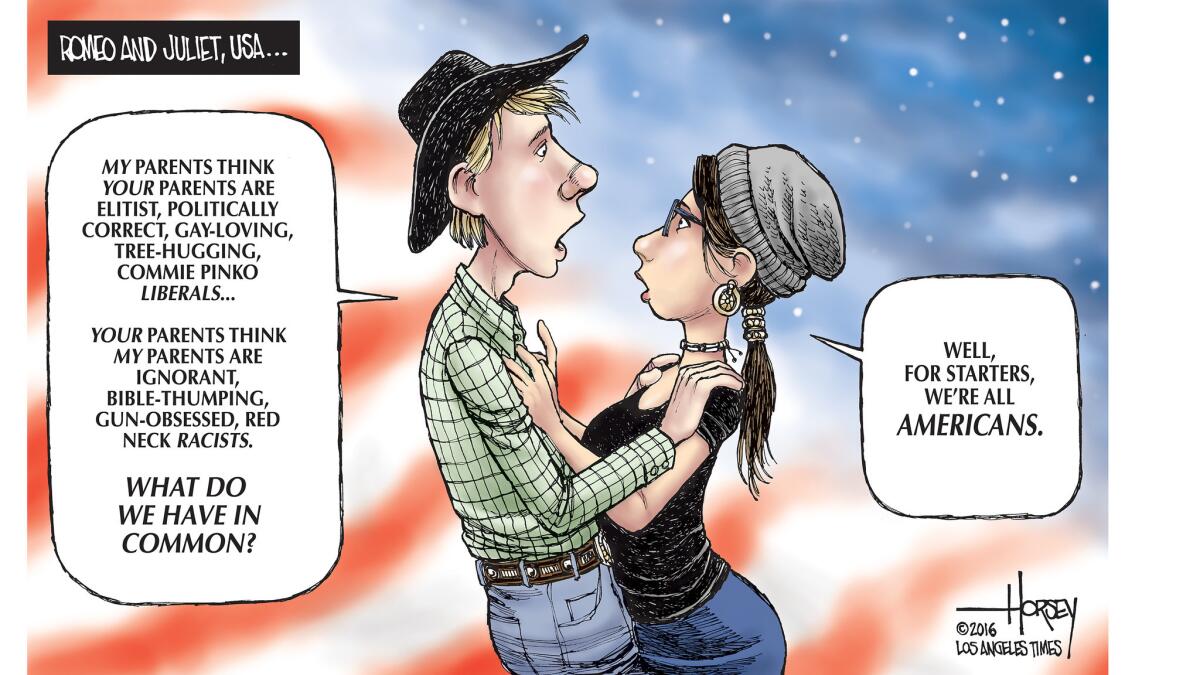

A political divide is nothing new in the United States, and there have been other times when the split ran along geographic lines — the Mason-Dixon Line, in particular. The element that feels new in my lifetime, however, and the one that I find more and more troubling, is the extreme polarization that has overtaken the country, polarization that has descended into demonization. These days, too many of us look at people with different views as enemies with evil intent, not as fellow citizens with whom we merely disagree.

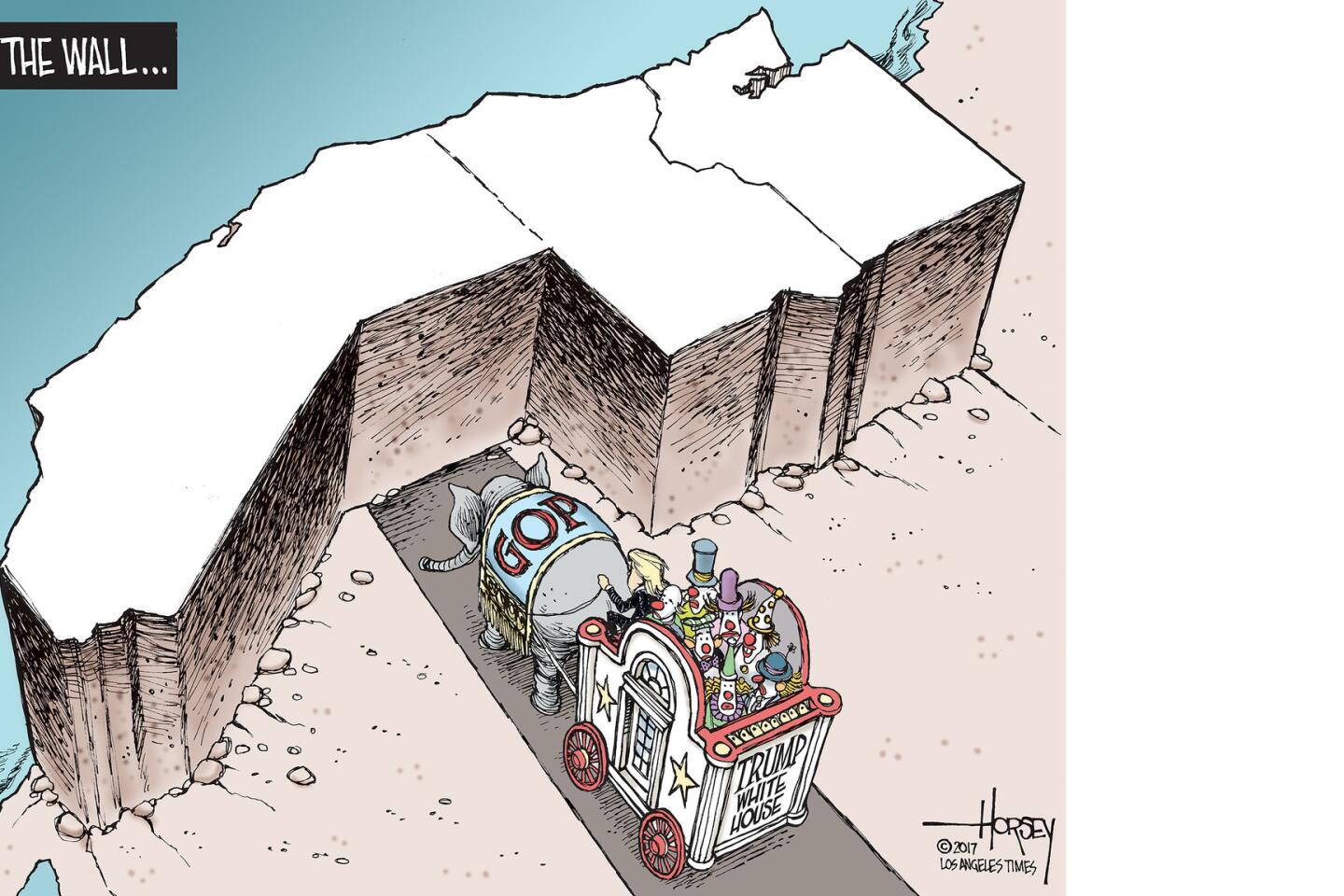

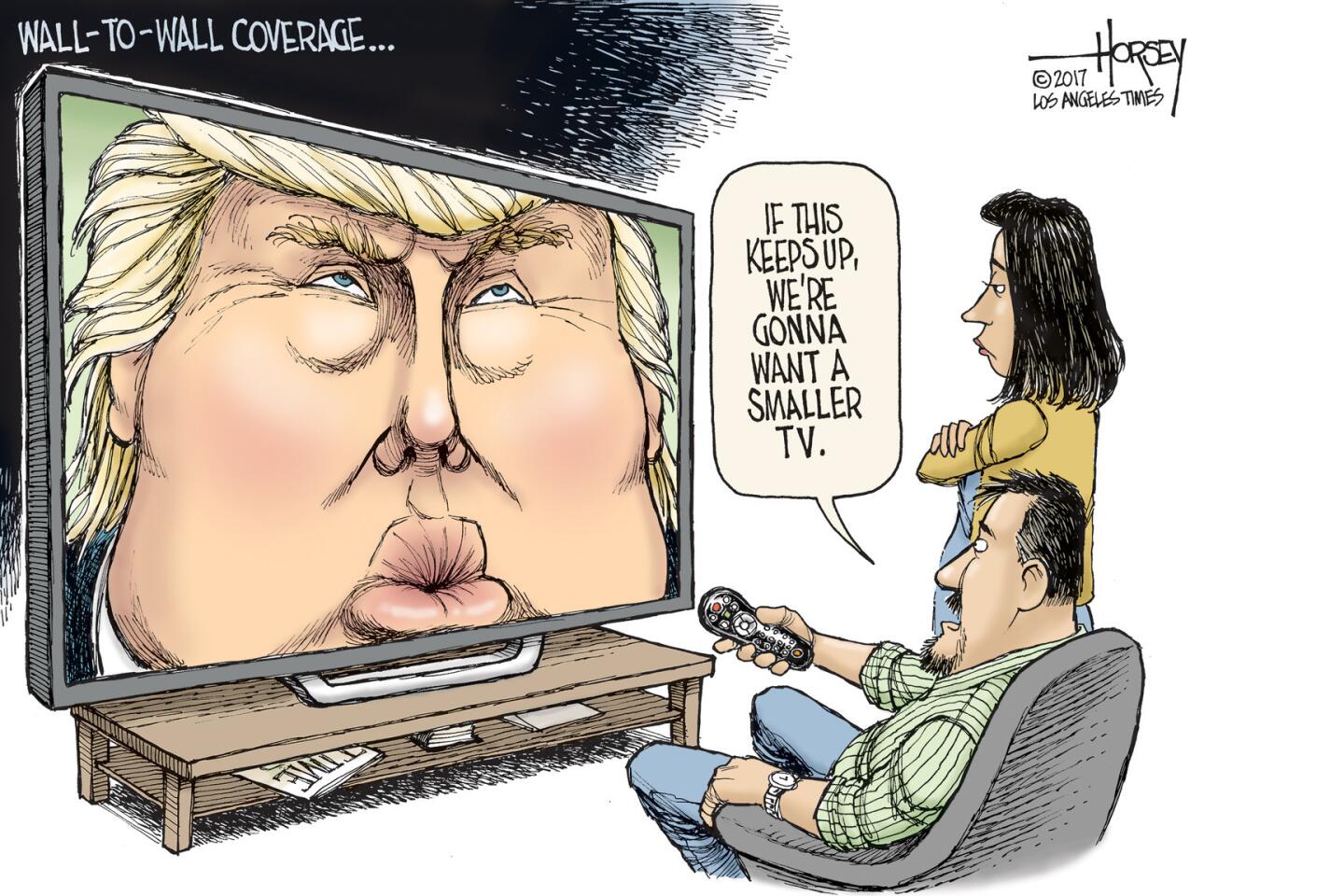

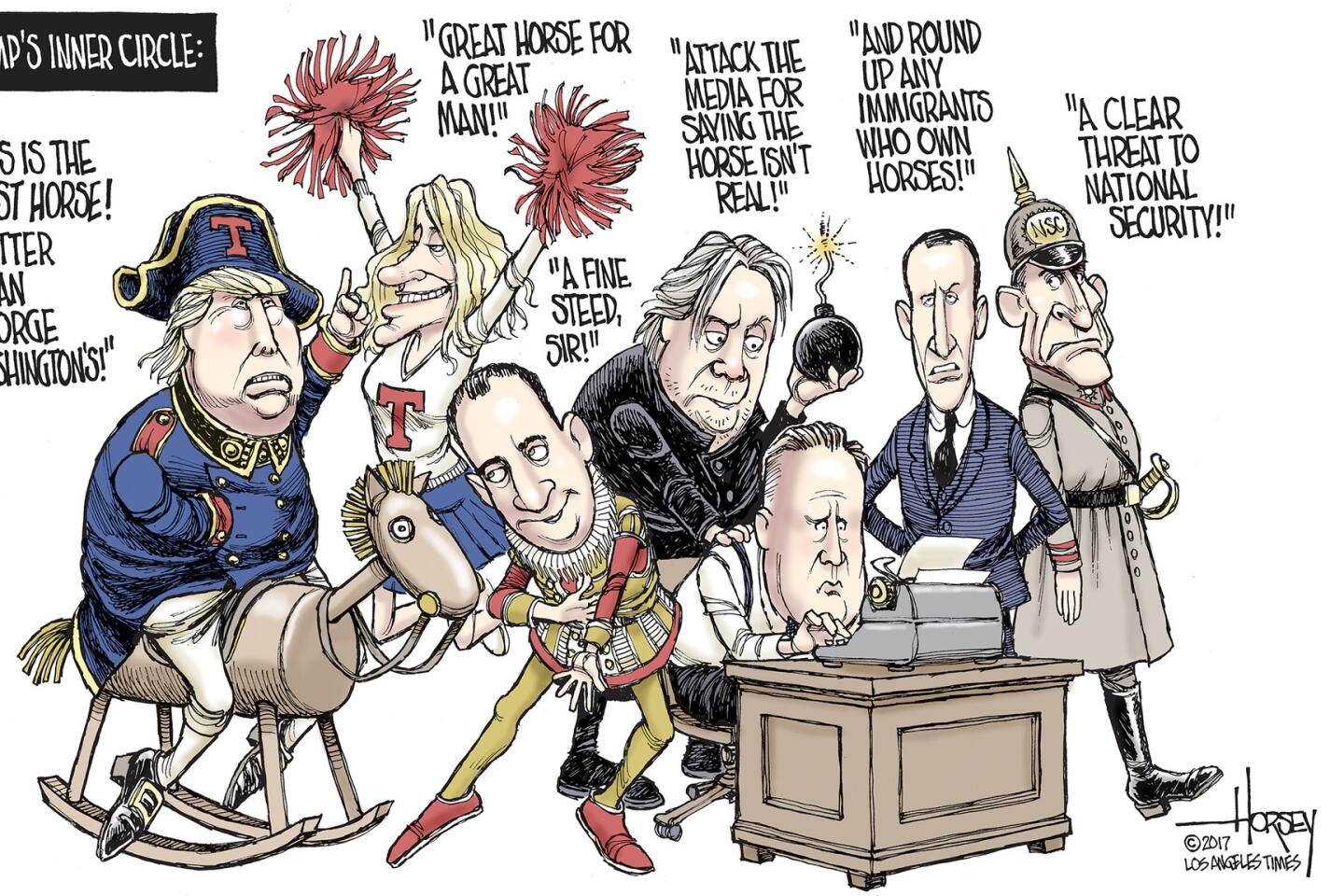

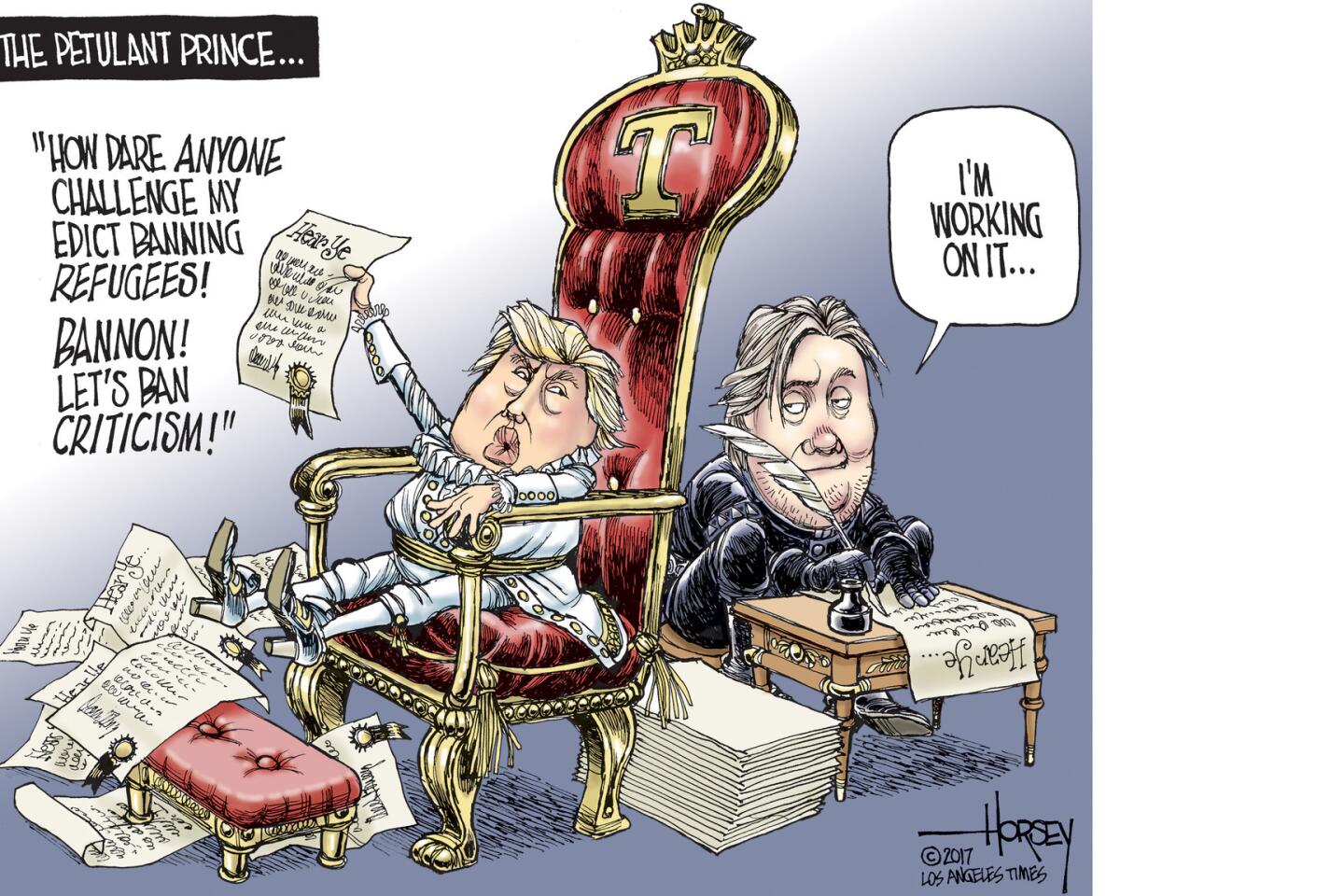

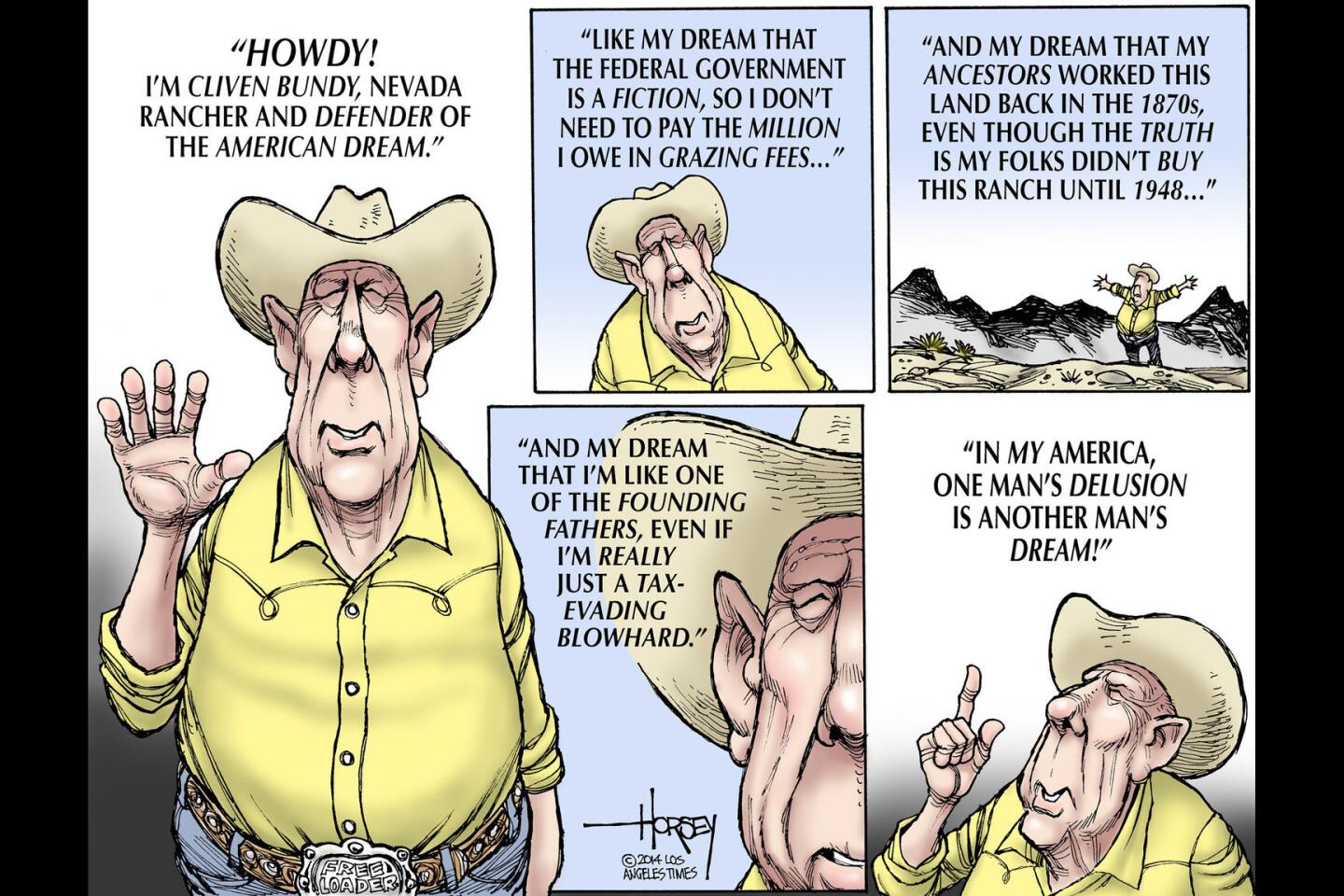

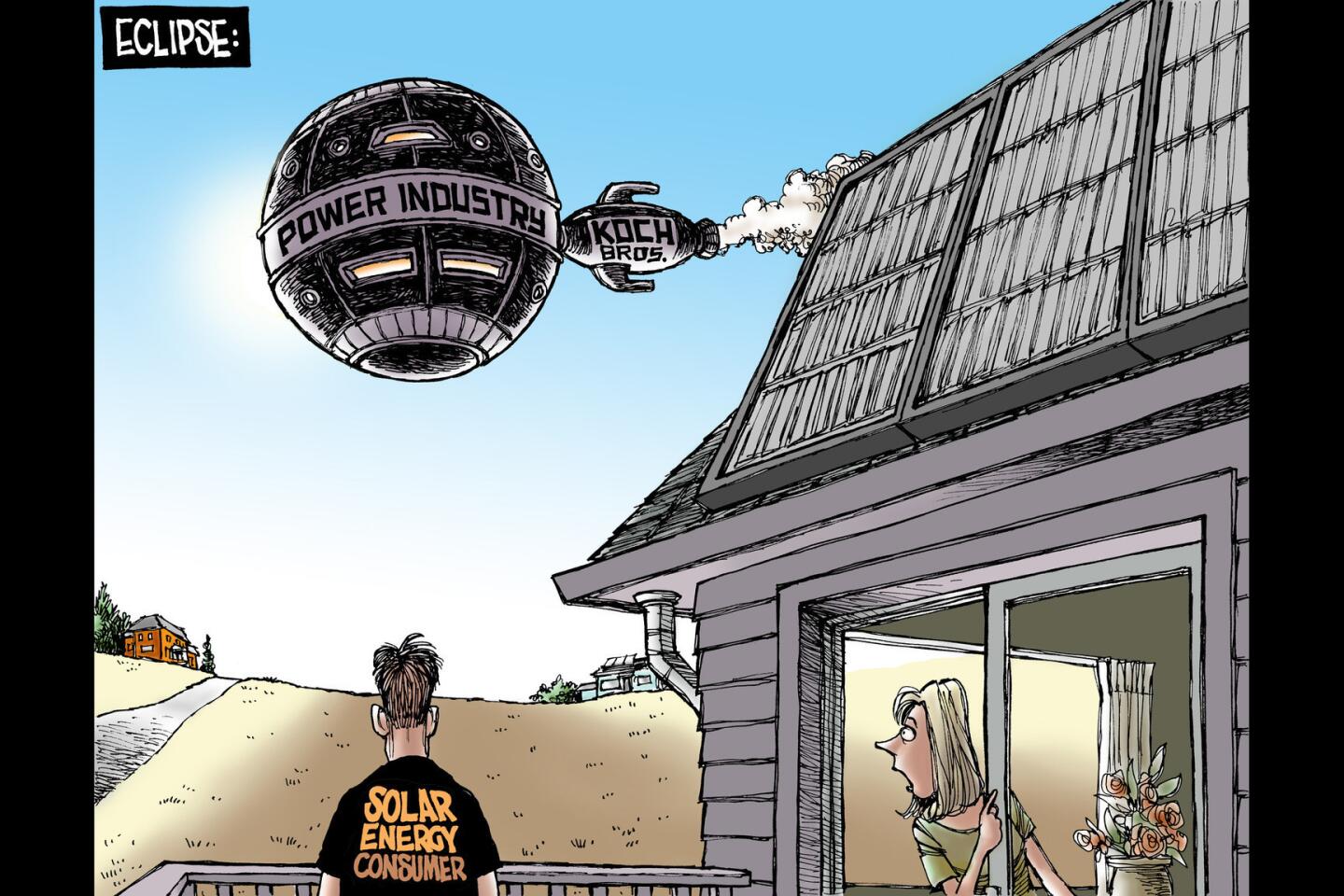

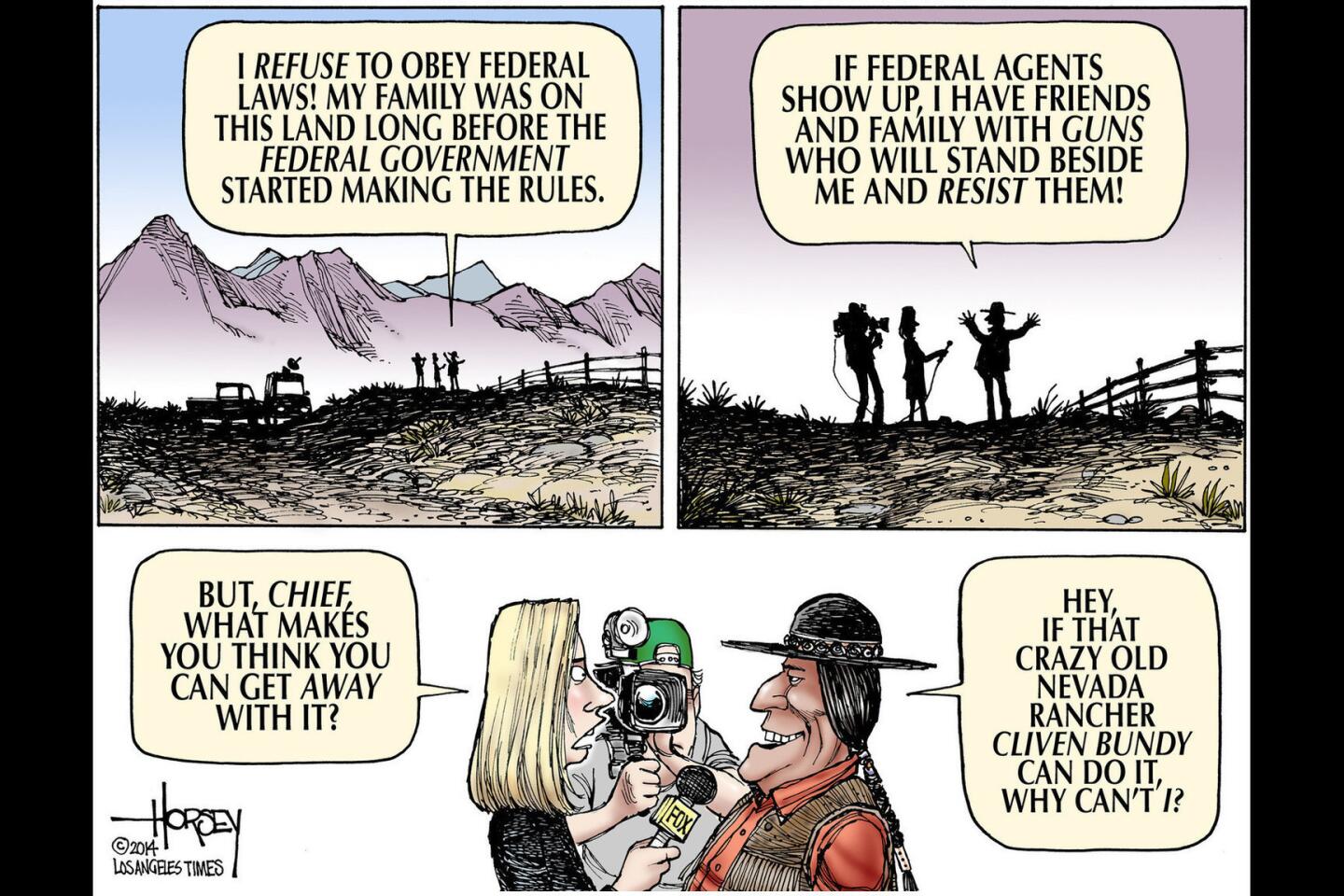

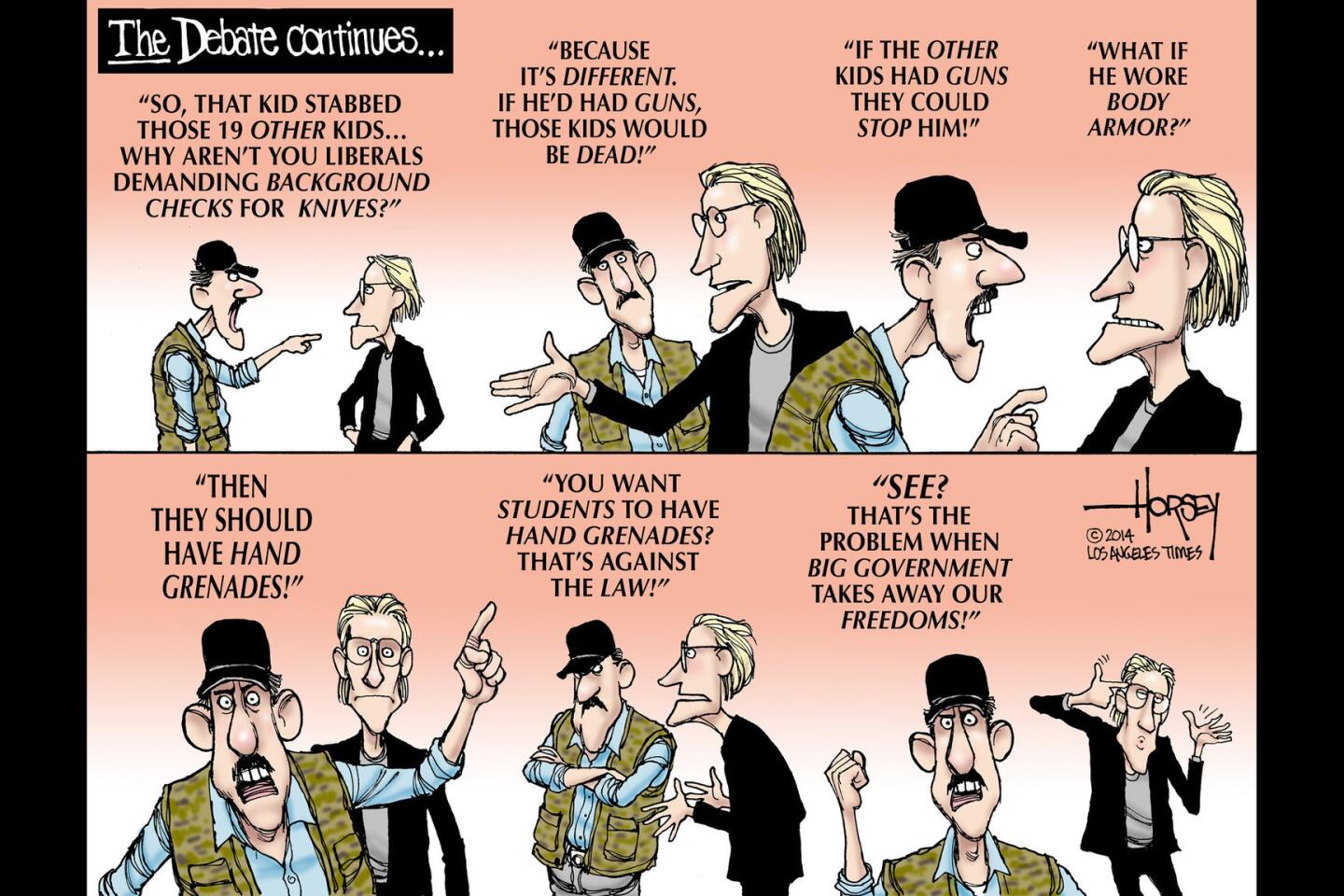

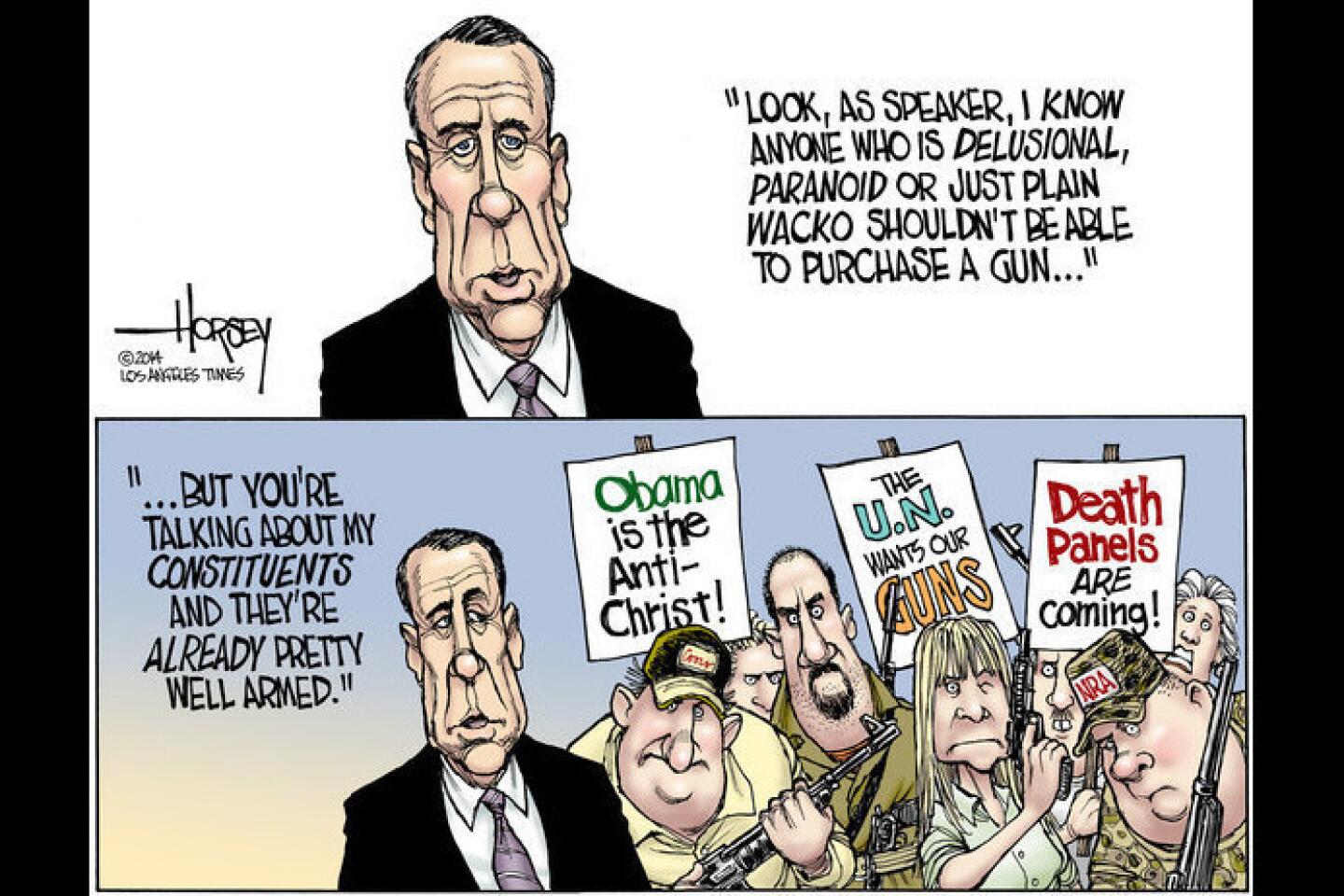

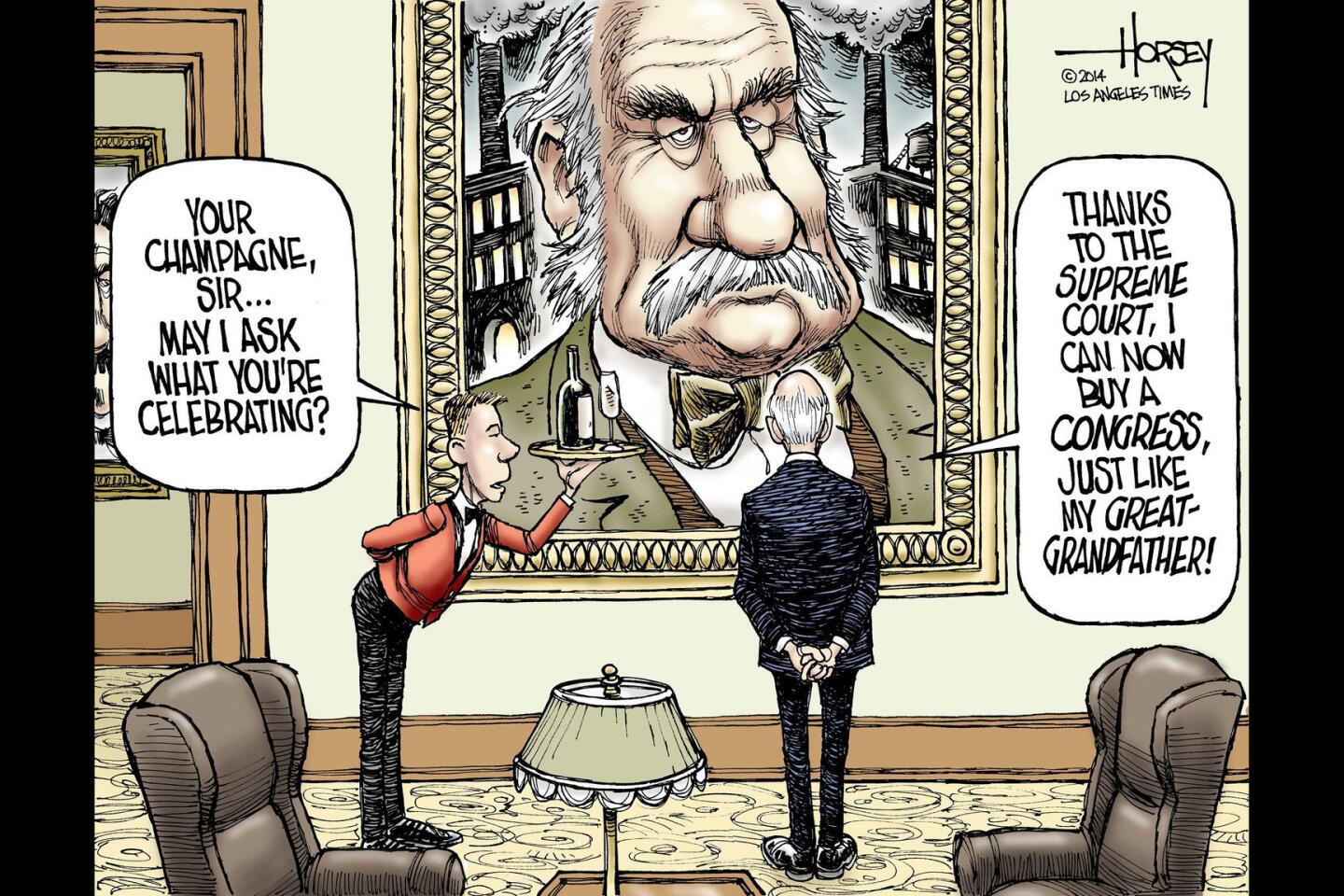

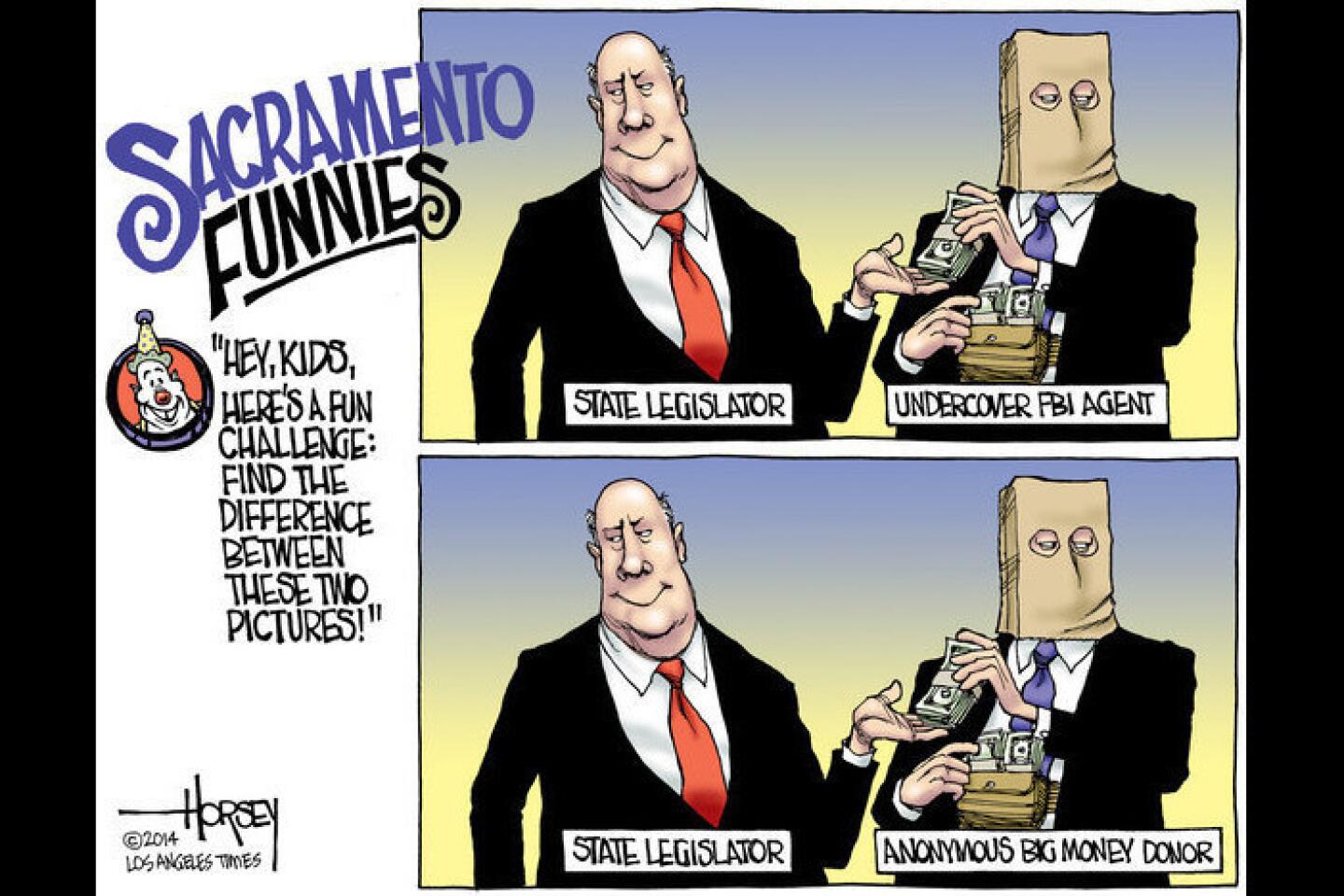

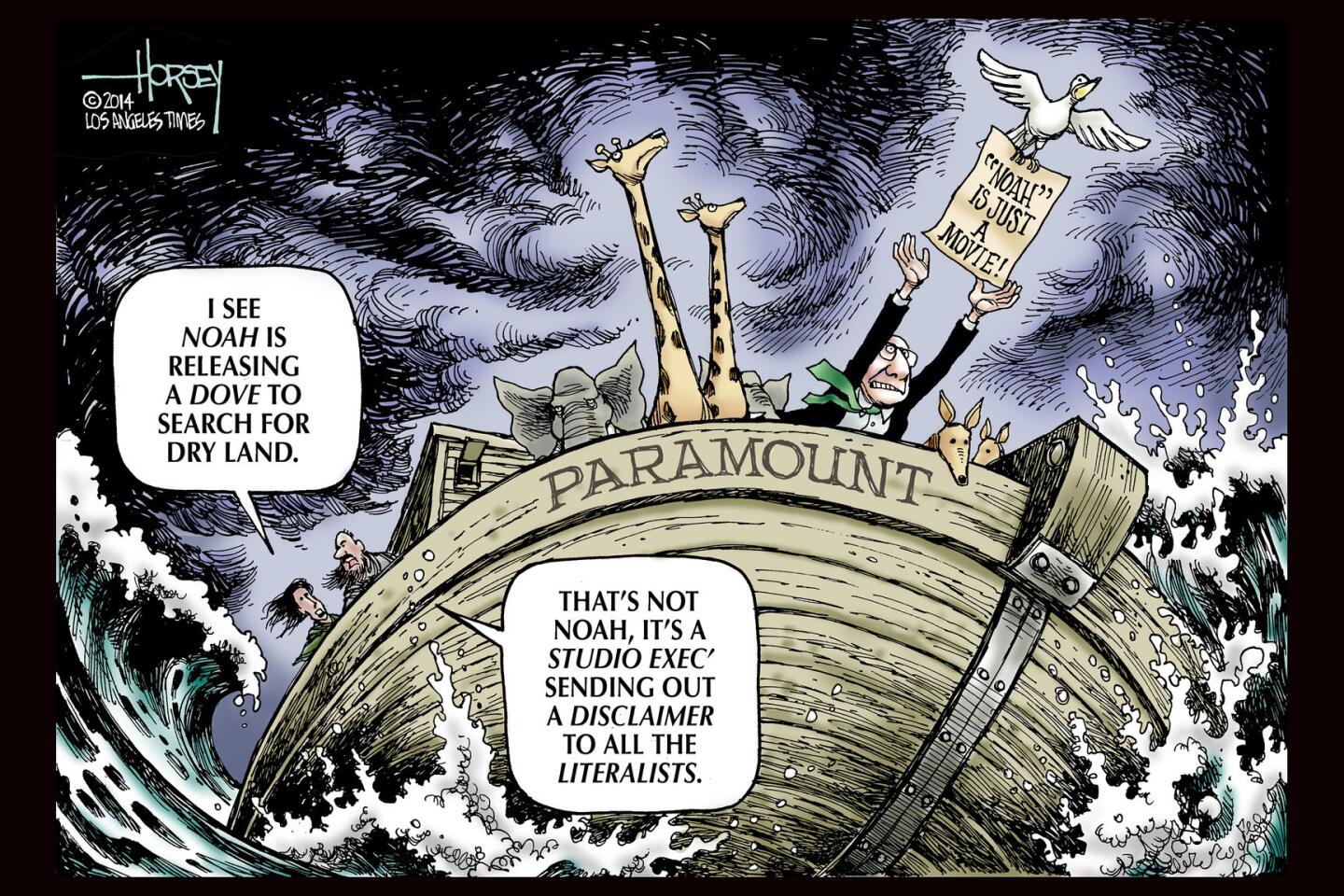

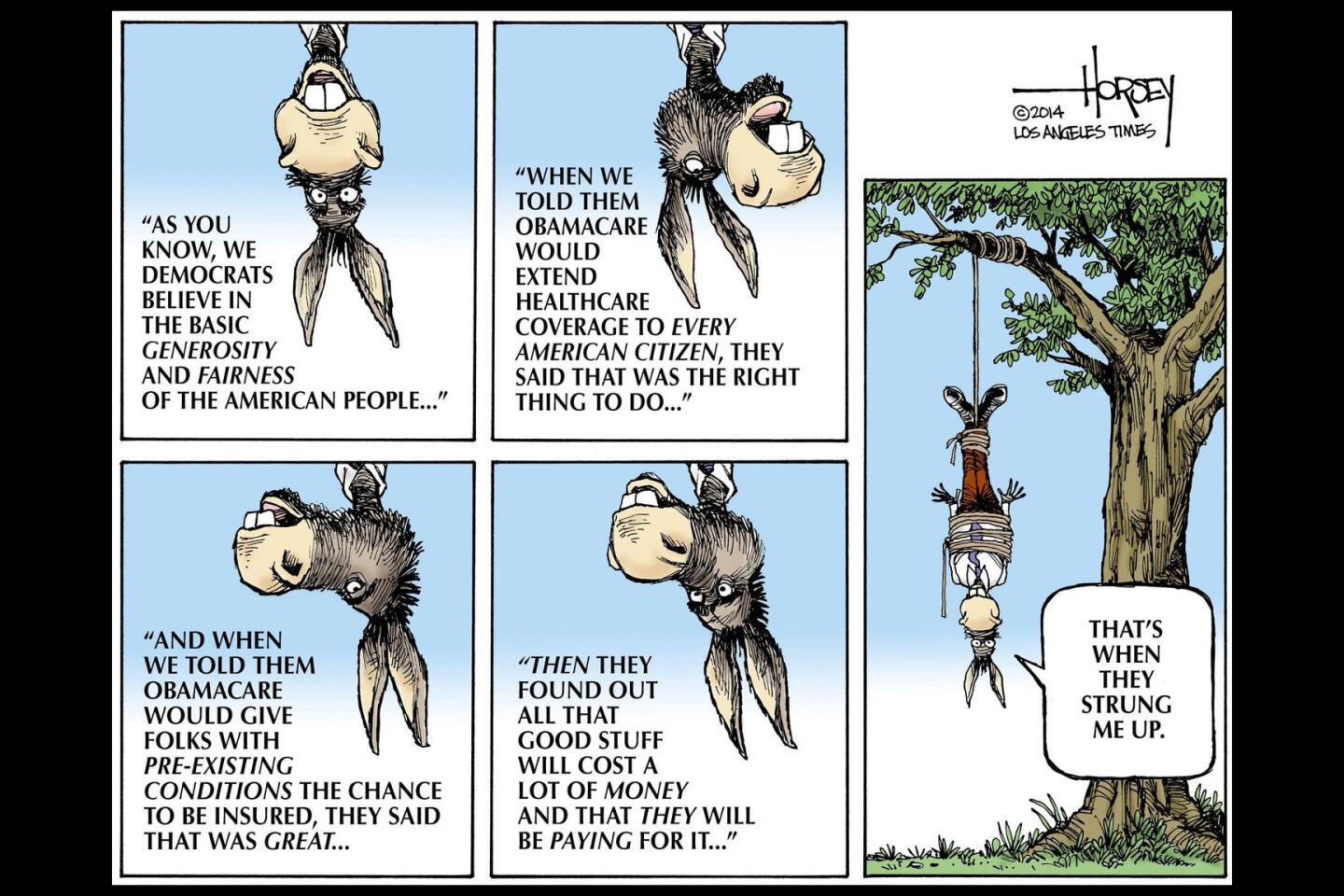

I place much of the blame for this phenomenon on the partisan media — including talk radio and Internet blogs — that turn every philosophical dispute into a fight for the soul of the nation. On the hard right, liberals are caricatured as anti-American subversives just a small step short of Venezuelan socialist goons. No room is allowed for compromise or common ground. Debate devolves into shouted epithets.

On the progressive side, there is also blame to be assigned. People who live in small towns and work on ranches and farms are all too often perceived by urban liberals as a dying breed of intolerant hicks who, in the infamous words of 2008 presidential candidate Barack Obama, “cling to their guns and religion.”

With this hyped-up rancor and shallow stereotyping in mind, my new friend Jim and I quickly agreed that it is past time for every one us to remember we are all “real” Americans with far more in common than we think. Then we had another beer and talked about cattle, kids and the loves of our lives.

My wife and I met up with Jim and Heidi again on Sunday night at the rodeo in Belle Fourche. It had been a hot, sunny day, but as soon as the last bull rider came out of the chute to be dumped in the dirt of the arena, the looming clouds unleashed a sheet of rain. A wild wind ripped across the grandstand. Lightning streaked the sky from three directions. The rodeo was supposed to end with a big fireworks display and the folks in charge of the pyrotechnics decided not to delay. For the next 30 minutes, a starry array of explosive devices sparkled in the stormy darkness while patriotic songs boomed out of the loudspeakers.

Jim and Heidi departed early to go stand watch over their ranch, just in case the lightning hit too close. I was left with my wife and my other friends to enjoy the spectacle of man-made fireworks backed by nature’s explosive power. For me, there was a bit of symbolism in the moment. Despite the storm, the celebration of American independence went on, just as this country and its people have always forged ahead, rising above stormy politics and the bitter winds of partisanship.

My hope is that we will keep on keeping on — together. As Teddy Kennedy observed back in 1980, no matter who wins or loses an election, there is still a nation to be perfected and a people needing to shape a common destiny. “For all those whose cares have been our concern,” Kennedy said back then as I watched in the convention hall and Jim listened by radio on the banks of the Yellowstone, “the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives and the dream shall never die.”

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.