Capitol Journal: Political power should be decided in elections — not rigged census surveys

Reporting from Sacramento — Gov. Gavin Newsom and California Democrats are determined to beat President Trump next year — not only on the ballot, but also in the census count.

There’s widespread suspicion that Trump is gaming the decennial census in an effort to reduce California’s political clout and federal funding.

Trump loves to poke California in the eye. And it’s understandable. This blue state is his most pesky tormentor, resisting in court or with legislation a lot of what he tries to do — especially his efforts to block unlawful immigration and deport migrants who are here illegally.

The president is striking back at California by placing on the census questionnaire — if the Supreme Court allows him, as expected — a query asking people whether they are U.S. citizens. He insists the information is needed to help enforce the Voting Rights Act.

Yeah, sure!

California officials fear many undocumented immigrants will simply refuse to participate in the census, even though they’re not being asked about their legal status.

“Immigrants are very skilled at avoiding government and they really don’t trust the Trump administration,” says Karthick Ramakrishnan, a UC Riverside political science professor and immigration expert. “The citizenship question is just adding fuel to the fire.”

The problem for California is that federal funding of state and local programs is based on population. And so is the apportionment of congressional seats. California could lose billions of federal dollars and at least one House seat — along with an Electoral College vote that helps determine who wins the presidency.

Related: A census undercount could cost California billions — and L.A. is famously hard to track »

So Newsom has asked the Legislature for $55 million — on top of $100.3 million previously approved under Gov. Jerry Brown — for a robust campaign to persuade all Californians to fill out census questionnaires. The governor has appointed Secretary of State Alex Padilla to run the operation.

The scuttlebutt within immigrant communities is about how the U.S. government used census data in World War II to round up Japanese Americans and send them off to internment camps. It’s now illegal to use census information that way. But Trump’s rhetoric and record — separating children from their refugee mothers, for example — hardly engenders trust.

“Everyone’s talking about Manzanar,” says USC demographics professor Dowell Myers, referring to the former internment camp in Owens Valley near Mount Whitney. “Just discussing this generates fear.”

Myers, a longtime Census Bureau adviser, says “the real problem here is that the president seems intent on overturning all conventions and destroying vital trusts. He’s sowing dissension and chaos at a time when we need stability.

“We’ve got the Russians on one side and now we’re getting it from our own administration on the other.”

But there’s fault all around, Myers adds.

“I blame the liberals for making themselves targets by being sanctimonious and acting high and mighty,” the professor says. “They’re know-it-all, like the school teacher who tries to discipline children.

“By not giving Middle America more respect, they’ve left the barn door wide open for Trump to go in and steal the horses.”

There are 2.2 million immigrants in California illegally, according to the latest estimate of the Pew Research Center, 100,000 fewer than its previous calculation. Under the U.S. Constitution, they’re supposed to be counted like everyone else.

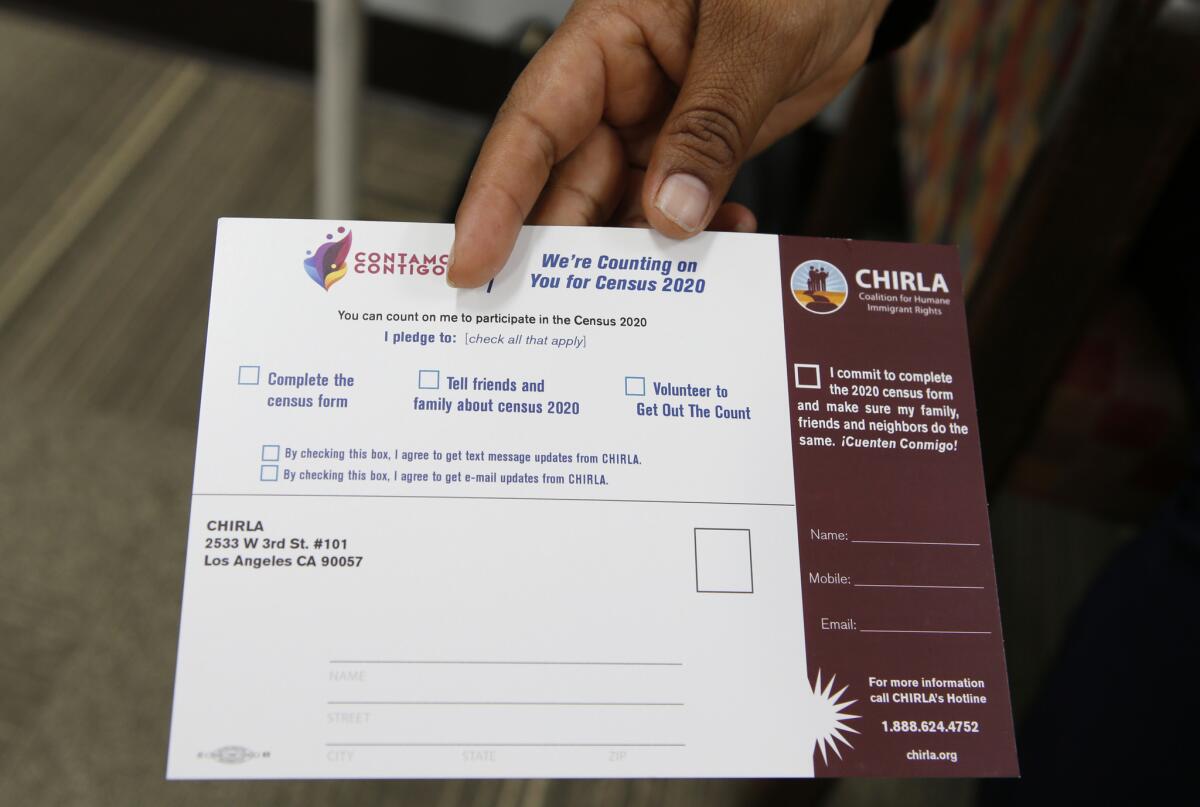

Newsom, the Democratic establishment and activist groups aren’t only worried about undocumented immigrants not being counted. They’re also concerned that citizen immigrants won’t participate, fearful of tipping off the household presence of undocumented relatives. California is considered a “hard to count” state anyway because of the homeless population, frequently moving renters and migrant workers.

Related: Are Arabs and Iranians white? Census says yes, but many disagree »

On top of that, the 2020 census will be conducted online for the first time. Many people still don’t have internet access. There’ll be an effort to contact them personally.

Experts are anticipating a 2.7% undercount. Newsom’s finance department estimates it would short California’s total population by 1.1 million residents. For each person not counted, it would mean $1,100 less annually in federal money — significantly down from an estimate last year of nearly $2,000. Still, over a decade that’s a $12-billion loss.

And if that many people aren’t counted, California surely would lose a congressional seat for the first time. We’d drop from 53 to 52 — still by far the most of any state — and our electoral votes would fall from 55 to 54.

Congressional districts would become geographically larger with urban seats spreading toward the suburbs.

“As they spread, it weakens the political strength of Latinos,” says Paul Mitchell, who runs Political Data Inc., which generates voter demographic statistics. “It would strengthen suburban communities.”

Mitchell says the hardest-to-count House districts — and the most likely to be altered — are held by Democrats Jimmy Gomez of Los Angeles, Lucille Roybal-Allard of Downey, Juan Vargas of San Diego, T.J. Cox of Fresno, Jim Costa of Fresno, Nanette Barragan of San Pedro, Tony Cardenas of Los Angeles and Maxine Waters of Los Angeles.

Newsom and Democrats are treating the census like a political campaign. They’ll have TV and radio ads, photo-ops and door-to-door canvassers.

“It’ll be unprecedented for a census,” Padilla says. “We’re going to every corner of the state.”

As a journalist, I’m all for collecting as much information as possible about almost everything. Sure, I’m curious to know the exact breakdown of citizens and non-citizens. But in this case, the questioner can’t be trusted.

Reductions in federal funding and shifts in political power should be decided in Congress and elections — not in rigged census surveys.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.