Charity becomes a lifeline even for Americans with health insurance as deductibles soar

ROELAND PARK, Kan. — “I’m scared, Mommy,” Bo Macan protested.

Bo, who is 9, was trying to be brave as a nurse probed his bare chest with a needle, seeking a surgically implanted port below his skin where she could attach an IV line for his weekly antibiotic.

For the record:

10:38 a.m. Aug. 5, 2019An earlier version of this article misidentified the title of GoFundMe’s leader and the time frame during which funds were raised for medical-related campaigns. Rob Solomon is the chief executive of the company, not the chairman. And the figure for the total amount raised — more than one-third of $5 billion — was as of June 2017, not annually.

“It hurts. It hurts! Please make it stop,” Bo pleaded, clutching his mother’s hand more frantically with each push from the needle.

Taking care of Bo — who was born with a unique combination of complex illnesses that have required 53 surgeries and more than 800 days in the hospital — is a full-time job for Carolyn Macan.

Macan also spends a lot of time looking for money.

“It just breaks you down,” she said.

Medical charities and crowdfunding have long helped fill the gaps for Americans who lack health coverage.

Now, Americans who have insurance are increasingly turning to charity as a lifeline, as a revolution in health insurance has driven up deductibles more than threefold over the last decade, forcing tens of millions of Americans to delay care and make difficult sacrifices to pay medical bills.

The average deductible for an individual health plan obtained through a job is now $1,350, according to an annual employer survey by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. One in four workers have deductibles of $2,000 or more.

“It’s not the uninsured who are the problem,” said Bari Talente, executive vice president of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. “It’s the underinsured.”

The Macans — including Bo’s parents and three siblings, who squeeze into a modest home in a working-class Kansas City suburb — are covered through Bo’s father’s job.

The plan has a $2,700 deductible and an out-of-pocket maximum of more than $7,000. So, every year, the family must pay thousands of dollars in medical bills.

Friends and strangers have helped with T-shirt sales, a home run tournament, a benefit concert and an online GoFundMe campaign, to name just a few efforts.

But the growing reliance on charity — though sometimes celebrated in inspiring stories of generosity — means patients and their families must devote time and energy to raising money, often when they are most stressed and in need.

This threatens to widen inequalities, giving an advantage to those with more resources, larger social networks and stories better suited to dramatic online appeals.

Soaring deductibles and medical bills are pushing millions of American families to the breaking point, fueling an affordability crisis that is pulling in middle-class households with health insurance as well as the poor and uninsured.

Funding healthcare through charity can also distort markets, particularly for prescription drugs, research shows.

“We shouldn’t be the solution,” said GoFundMe Chief Executive Rob Solomon. “We know we’ve become a kind of de facto safety net.… But we’re only scratching the surface of all the need out there.”

GoFundMe, the nation’s largest online crowdfunding site, is now dominated by healthcare campaigns. An estimated one-third of the more than $5 billion raised through the platform as of June 2017 went to campaigns categorized by the organizer as medical, according to the company.

Major patient support groups such as the American Cancer Society and the breast cancer organization Susan G. Komen report that most of the calls they receive seeking help come from people who have health coverage.

FamilyWize, founded in 2005 to help uninsured Pennsylvanians get discounted drugs, calculates that at least three-quarters of the nearly 3 million people it serves nationwide are insured.

“More and more people who have insurance simply can no longer afford their medications,” said FamilyWize co-founder Dan Barnes.

“We shouldn’t be the solution.”

— GoFundMe Chief Executive Rob Solomon

Millions more Americans depend on assistance from foundations set up by drug companies that help patients get their products.

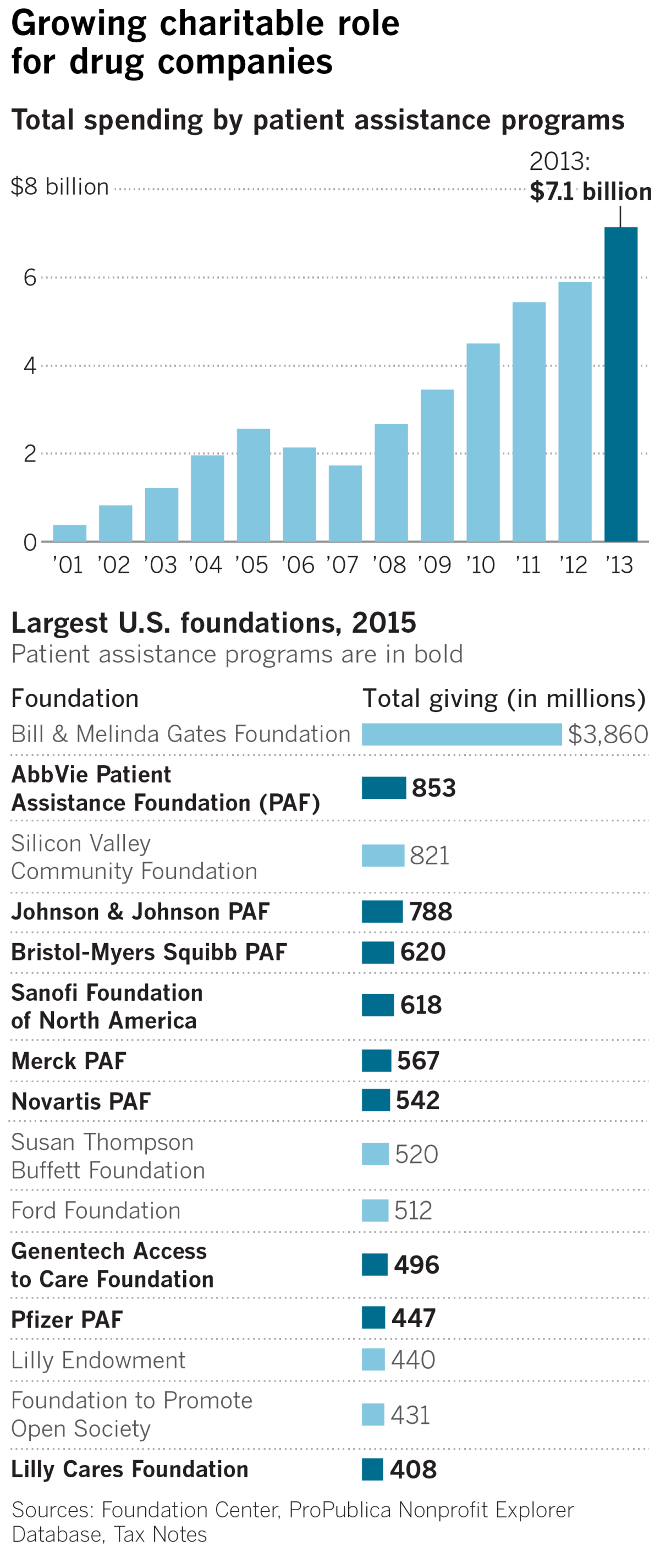

Industry support for these programs increased 14-fold between 1998 and 2014 and now tops $7 billion a year, a Treasury Department analysis found.

Nine of the country’s 15 largest foundations, as measured by giving, are affiliated with drugmakers, giving the companies large tax breaks while helping maintain high list prices.

The largest — the AbbVie Patient Assistance Foundation — reported it gave more than $853 million in 2015, second only to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, according to data from the nonprofit Foundation Center.

By one estimate, 1 in 5 brand-name prescriptions filled by someone in a commercial health plan now involves a coupon provided by a drugmaker.

The Macans never envisioned charity would be so important to them.

“I’ve had a job all my life,” said John Macan, 41, who works at a digital sign company. “I’ve never had to rely on others.”

Both John and Carolyn, who was a hairdresser, said they always lived within their means. They bought a small house with no garage next door to where Carolyn grew up. They never took lavish vacations and rarely ate out. They had two children.

Then, in 2009, Carolyn got pregnant with twins.

Bo and his sister were born 12 weeks early. The babies were tiny, weighing less than 3 pounds, and required long stays in the hospital.

Bo’s sister Brooklynn gained weight steadily. Bo struggled.

“I knew something was different with him,” Carolyn recalled.

At eight months, Bo was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, a form of the disease that requires regular insulin shots, frequent medical care and constant monitoring.

Doctors would soon discover a baffling set of other medical conditions, including a hormone deficiency that slowed Bo’s growth and an inadequate supply of immunoglobulin A, a critical protein that helps combat infections.

Bo developed chronic inflammations in his lungs and liver. At 4, he suffered his first seizure, nearly died from a massive infection and spent more than 200 days in the hospital.

He takes 17 prescription medications. And this summer, he was back in the hospital to have the broken port replaced.

Playing video games on the living room couch and gleefully shocking his grandmother with a stream of scatological jokes, Bo can seem like a typical 9-year-old.

Bo’s family labors to make life normal, helping him get to school when he feels up for it and taking him to watch his beloved Royals play baseball.

But he can’t play kickball or roughhouse with classmates at recess. He stays home during flu season because a simple cold can land him in the hospital.

“We have weeks that are wonderful,” Carolyn explained. “And there are weeks that are terrible. We just adjust.”

“When other moms say, ‘Let’s have wine on Tuesday night,’ I have to say I can’t. And eventually, people just stop asking. That’s OK. I don’t care about that kind of stuff.…

“I care that I live one mile from the hospital, and I can get there to be with my kid and get back to see my other kids for dinner. I care about being able to afford the prescriptions to make my son’s life better,” she said.

That’s often been a challenge for the Macans, who have an income of $85,000 a year for the family of six.

Carolyn is constantly on the hunt for funding to pay medical bills and cover other expenses, such as the cost of taking Bo to see specialists at Boston Children’s Hospital and the National Institutes of Health outside Washington.

“My husband won’t ask for help,” she said. “He’s too proud. But if there’s a chance we can qualify for something for Bo, I want to know about it.”

The Macans have been fortunate to have a supportive community.

“We are super lucky,” John said. “We have so many people in our life. I know many people don’t.”

Bo was a featured cause in the annual Rock Chalk Roundball Classic, a charity basketball game in Kansas featuring former players from the University of Kansas. A barbecue restaurant contributed food for a fundraising dinner and dance for Bo. Members of a local high school football team set up a Facebook page to raise money.

And last fall, one of Carolyn’s friends from high school set up a GoFundMe campaign that brought in $18,548 from 511 donors.

“Carolyn and John are just the most humble, hardworking people,” said Jennifer Dlugolecki, who had already organized a campaign for another friend with a sick child. “And they never complain.”

The Macans used $10,000 to pay off a credit card they had used for medical bills. They put the rest in a savings account in anticipation of more bills next year when the deductible resets.

“You never get used to having people do fundraisers,” Carolyn said.

“To say thank you just doesn’t seem like enough.… Sometimes, it feels like we nickel and dime the same people.”

While the Macans have managed to raise enough to cover many of their bills, most patients who turn to crowdfunding do not, said Nora Kenworthy, a public health researcher at the University of Washington Bothell who has studied online crowdfunding.

Kenworthy and a colleague found that only about 10% of 200 GoFundMe healthcare campaigns they examined met their targets.

Top-performing campaigns often featured middle-class families who suffered an unexpected setback. They showcase arresting photographs, invite viewers to join an online “team,” and provide frequent updates to a wide social network.

By contrast, families less skilled at using social media and less adept at presenting a compelling narrative about their suffering struggled at fundraising, the researchers found.

Donors responded less enthusiastically to campaigns that feature the kind of complex challenges poor patients commonly face, such as paying for food and housing or managing a chronic disease such as diabetes.

“These campaigns raise questions about who should be seen as most deserving,” Kenworthy said. “And they replace the notion of healthcare as a right with this hyper-individualized marketplace where people are forced to compete with one another to meet their basic needs.”

Drug companies’ charities present even more issues.

Researchers at the Yale School of Medicine and Harvard Medical School found, for example, that most drug coupons cover brand-name medications for which lower-cost alternatives exist, many of them generic drugs.

By using the coupons, patients can reduce their out-of-pocket costs, but health insurers must then pay the full cost of the drug.

This, in turn, allows drugmakers to maintain high prices and prompts insurers to raise premiums for everyone to cover the expense.

“These programs can look so appealing. Companies look like they are doing the right thing to help patients,” said Dr. Joseph Ross, a Yale internist who co-wrote the study. “But in many ways, this is just a way to keep the gravy train running for drug companies.”

Medicare prohibits the use of such coupons; the federal government considers them akin to illegal kickbacks. But they are still widely used in commercial insurance, which most Americans get through work.

For Carolyn Macan, the drug discounts are just one more headache.

When she went to fill a prescription for Bo’s insulin recently, the pharmacist told her it would cost $312 if she used her health plan. With a coupon, the insulin would be $154, but the expense wouldn’t count toward fulfilling her deductible.

“It’s insane,” she said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.