Buttigieg and Sanders lead in Iowa. Full returns still to come

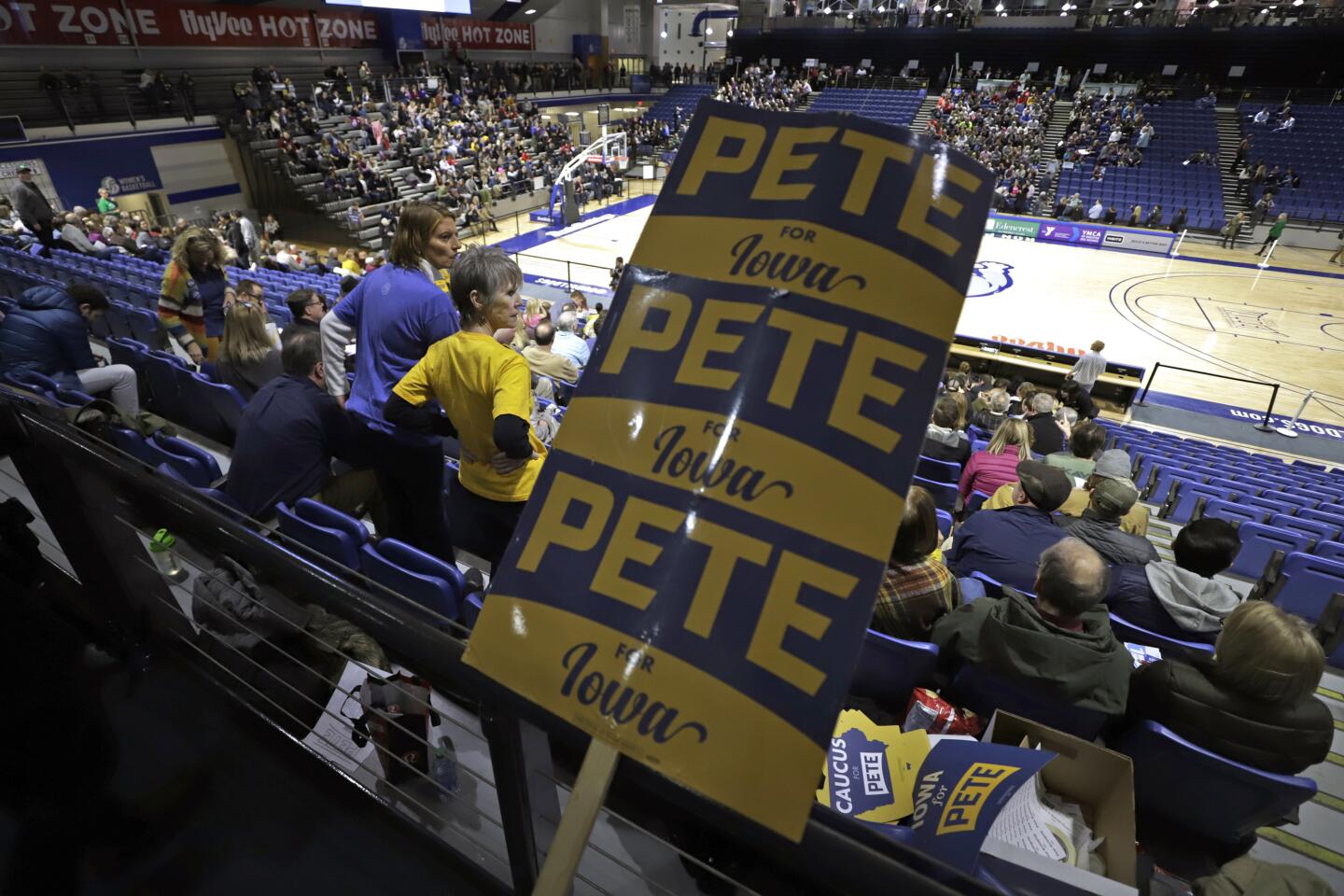

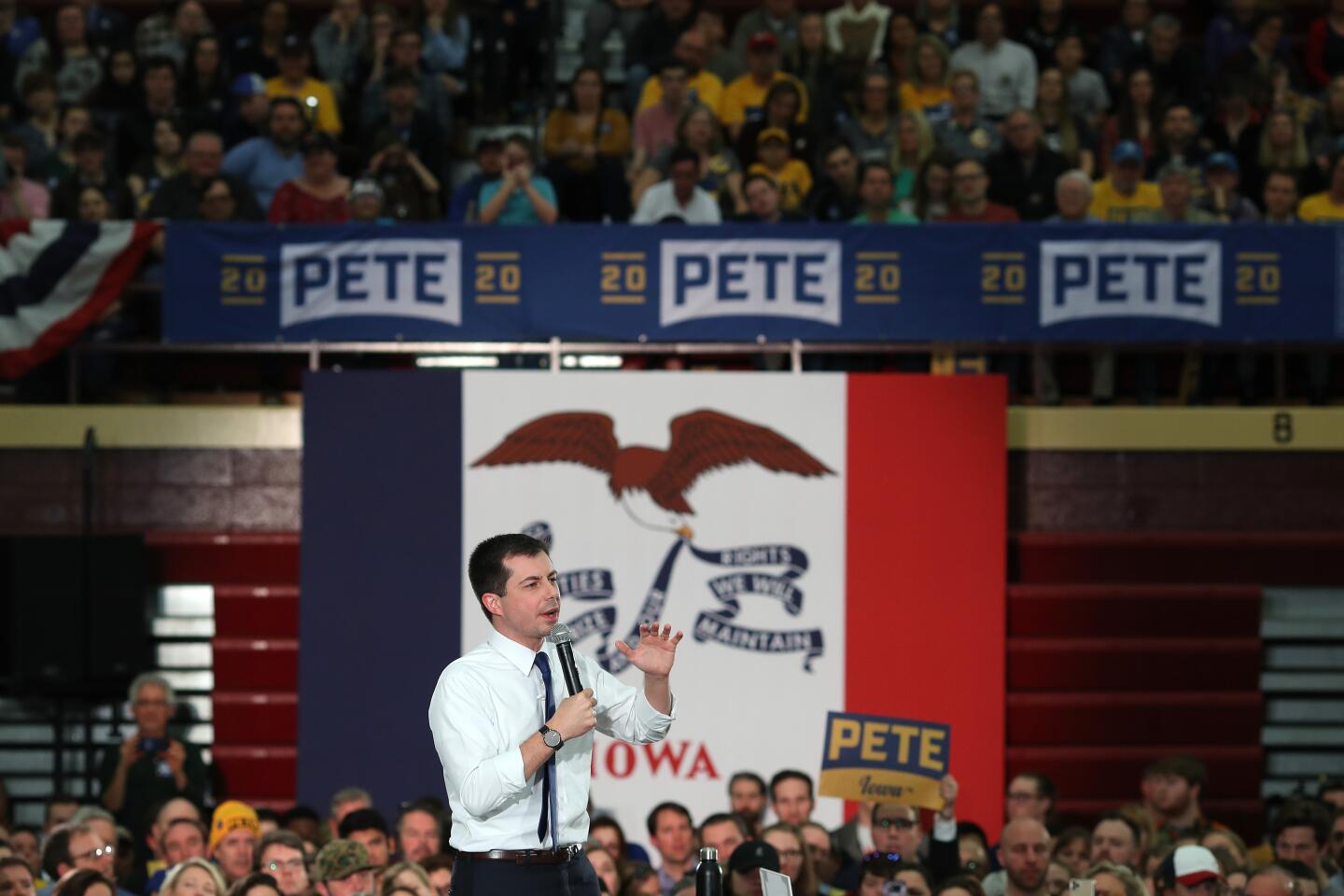

DES MOINES — Pete Buttigieg and Bernie Sanders sat atop the field Tuesday in partial returns from the Iowa caucuses, which left the contest unresolved and the Democratic presidential race in turmoil more than 24 hours after the votes were cast.

The results reflected 71% of returns, owing to a computer malfunction and other difficulties, with no word from the state party when the final outcome would be known.

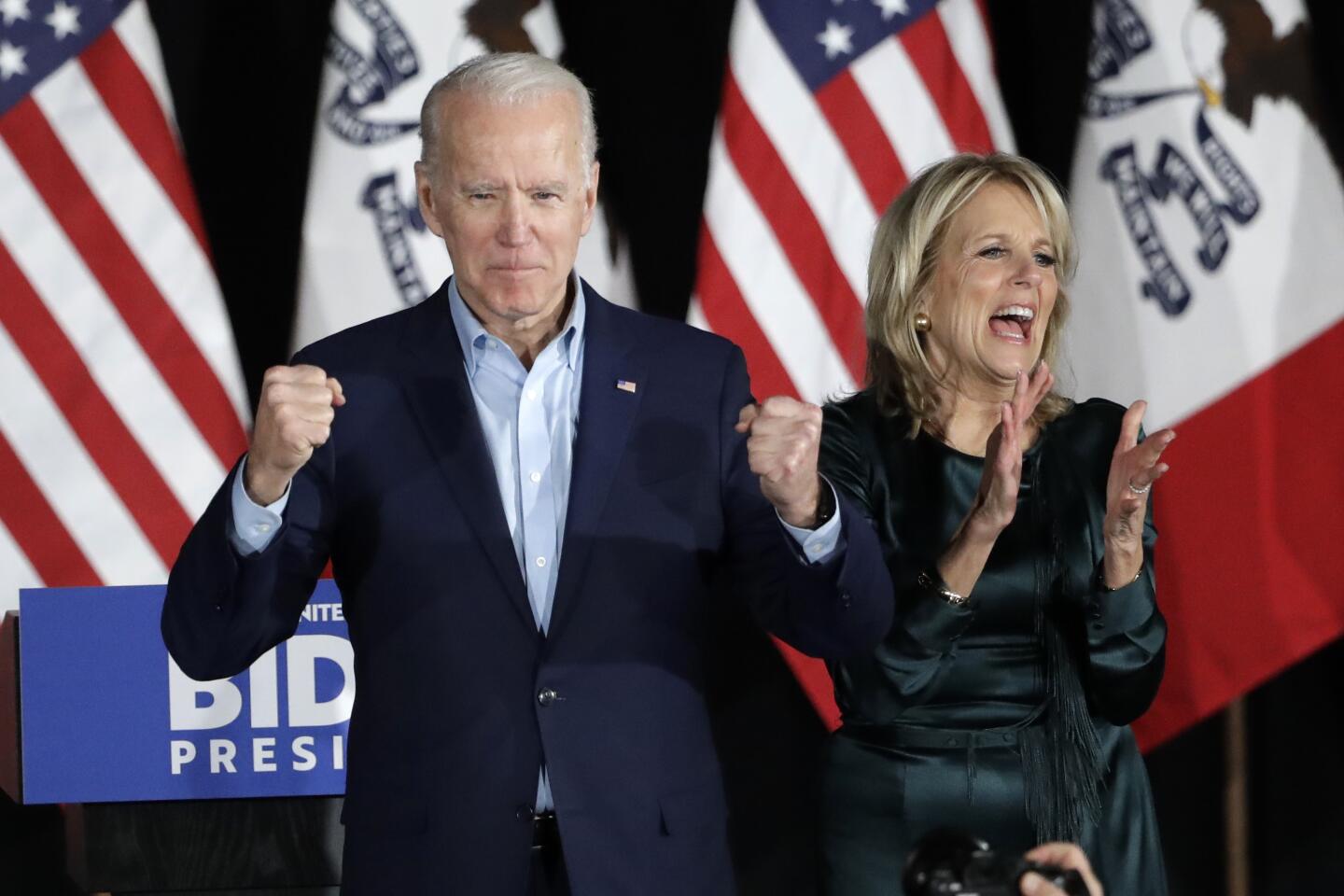

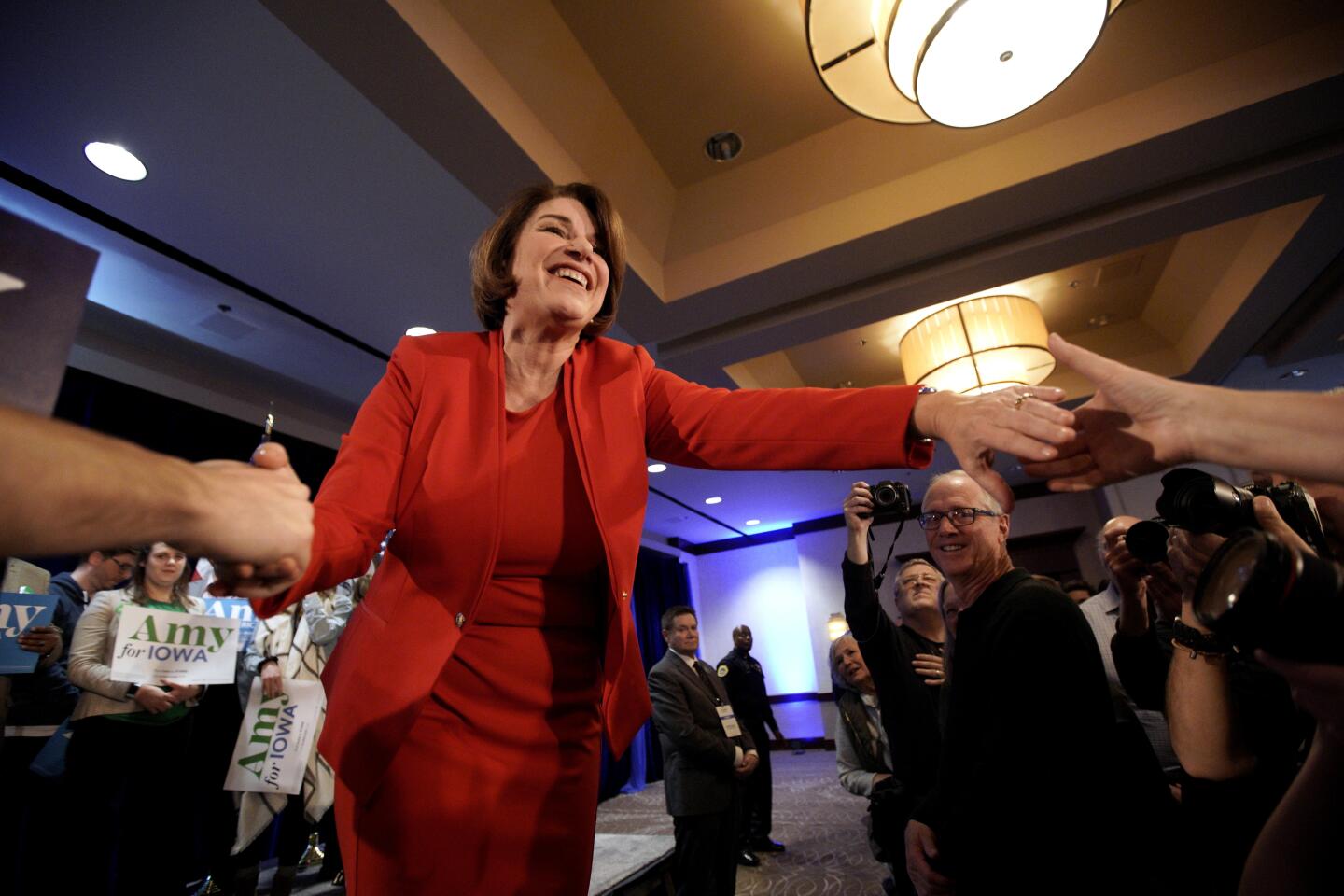

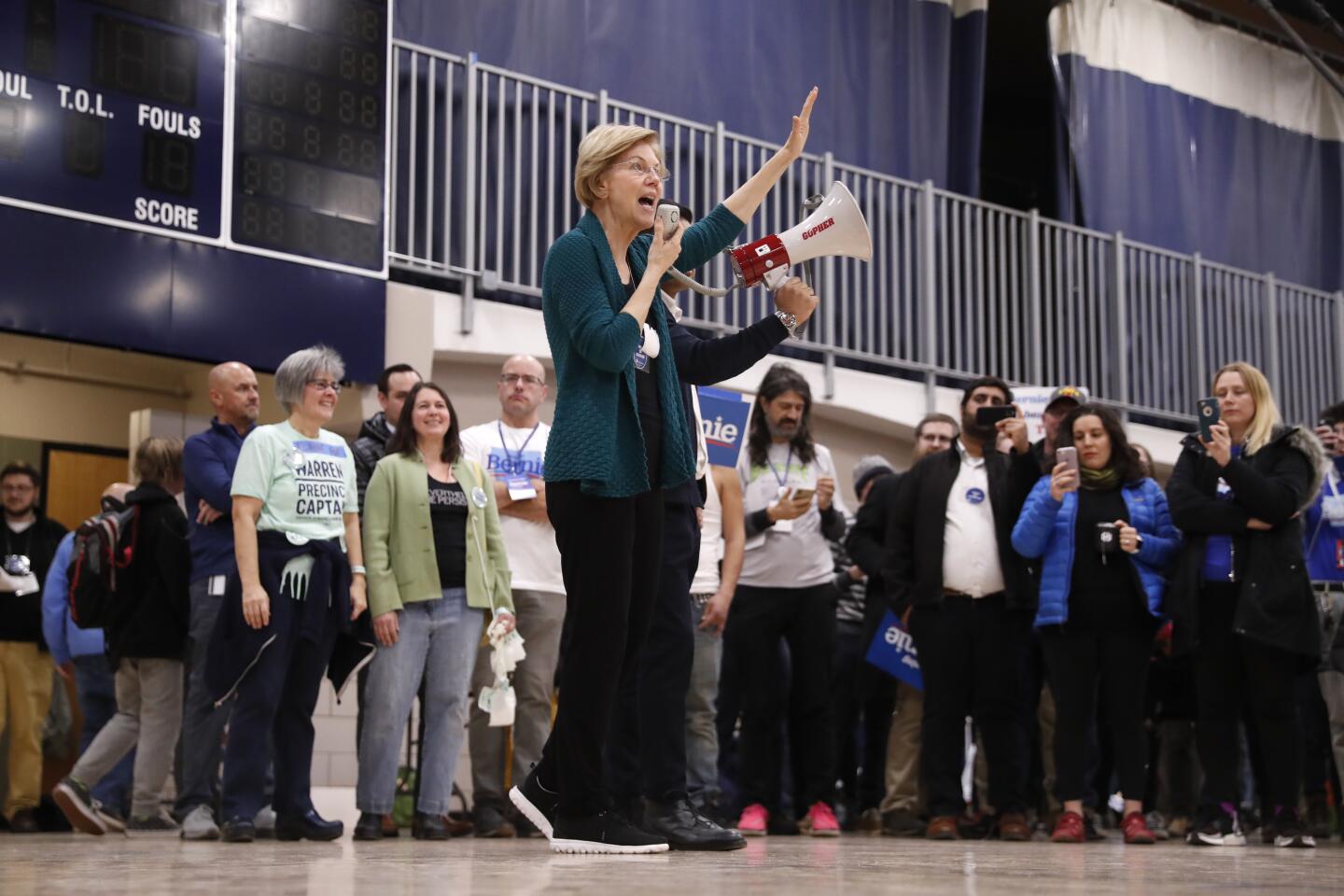

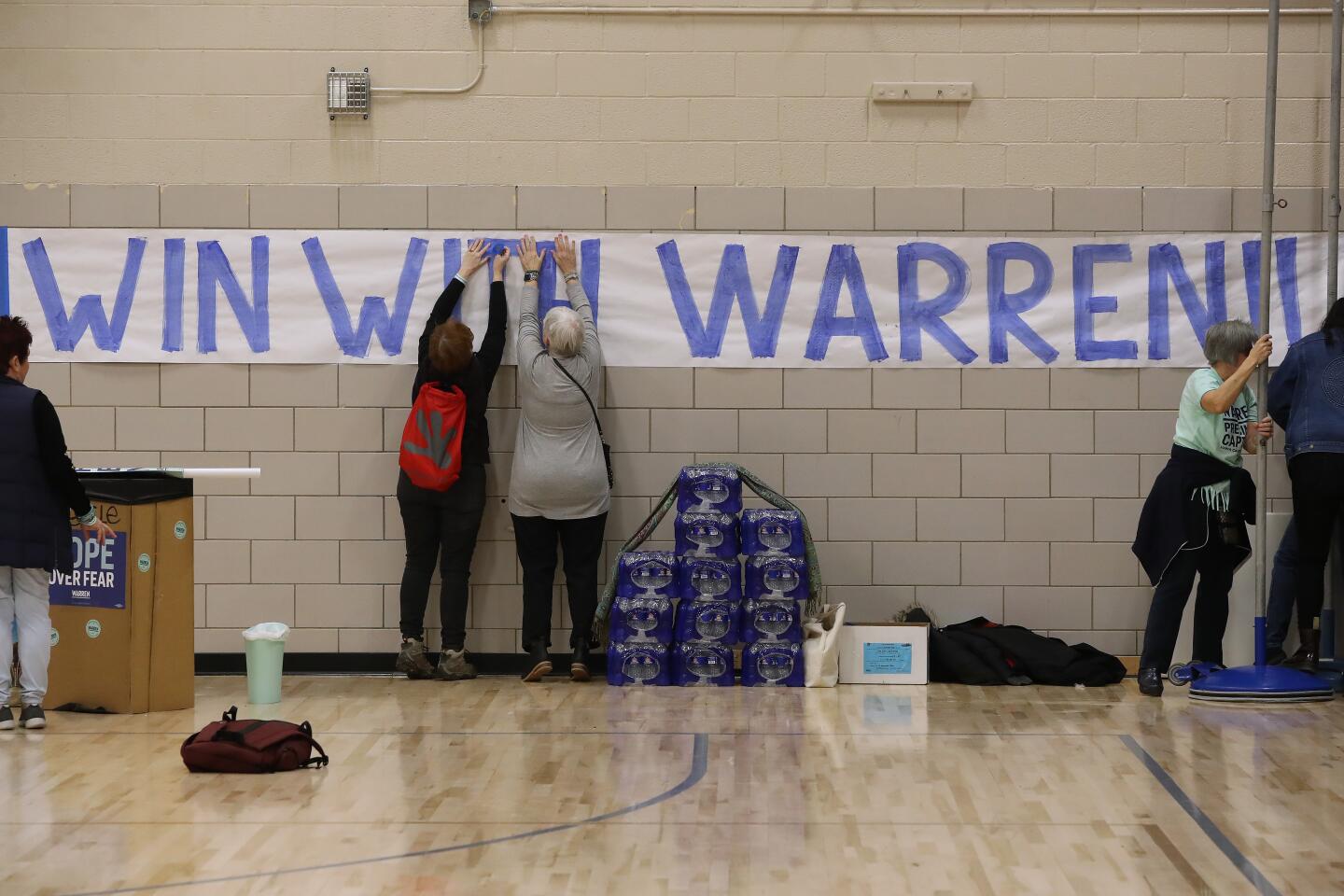

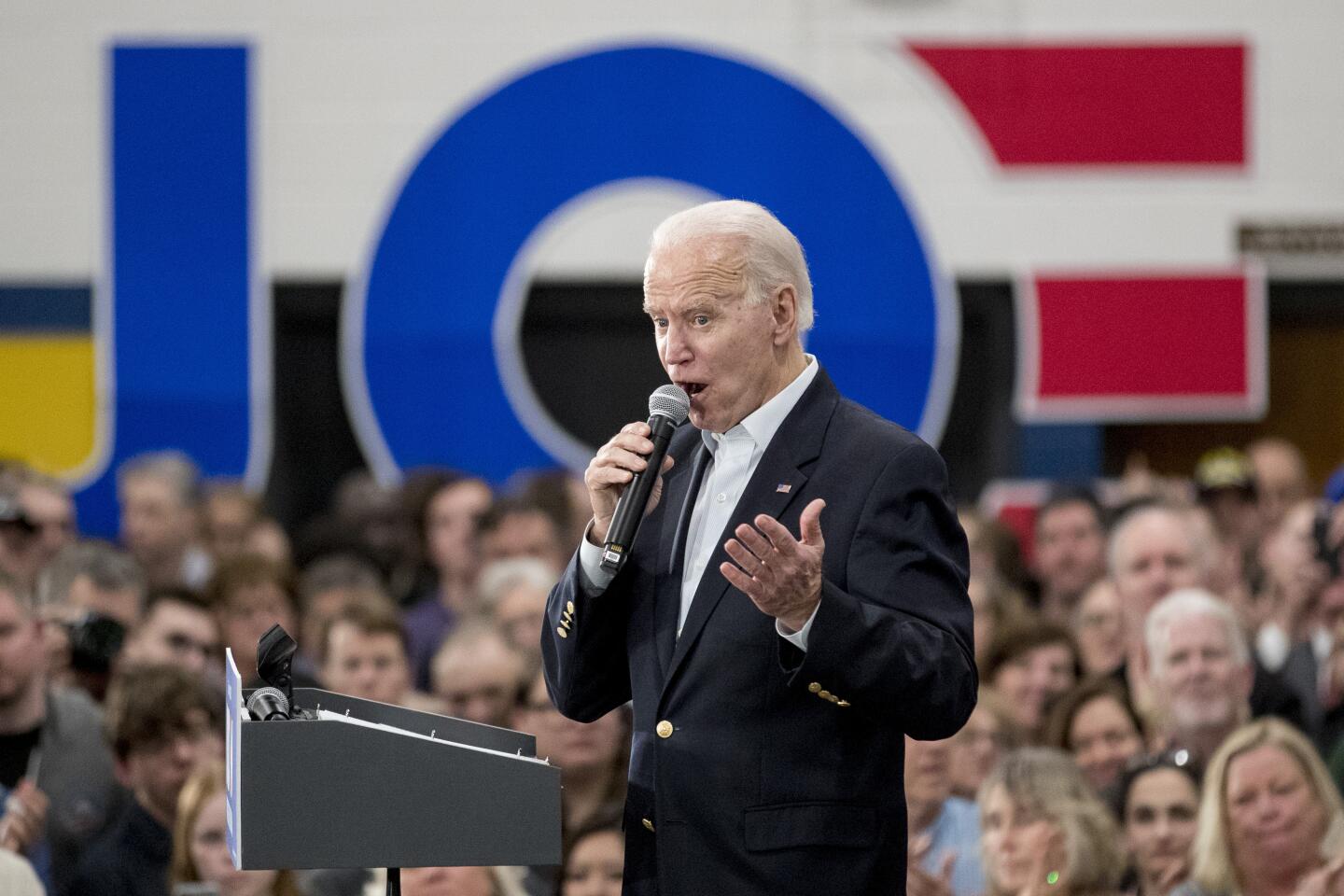

Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Ind., narrowly led Vermont Sen. Sanders 27% to 25% in state delegates awarded — the standard measure of victory in Iowa — followed by Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren with 18%, former Vice President Joe Biden with 15% and Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar with 13%.

No other candidate had double-digit support.

In a separate measure, Sanders led Buttigieg in the popular vote, followed by Warren, Biden and Klobuchar.

The results, should they stand up, would be a setback for Sanders, who nearly won the state four years ago and appeared to have the most momentum, and a big victory for Buttigieg, who a year ago was a political unknown with a hard-to-pronounce name and no political success beyond his hometown.

“It’s just an extraordinary validation for our belief that we can unify people,” Buttigieg said Tuesday on CNN after a New Hampshire campaign stop. “It amounts to a remarkable victory for our campaign’s vision and message.”

For now, however, Iowa’s full impact — like the outcome — remains to be seen.

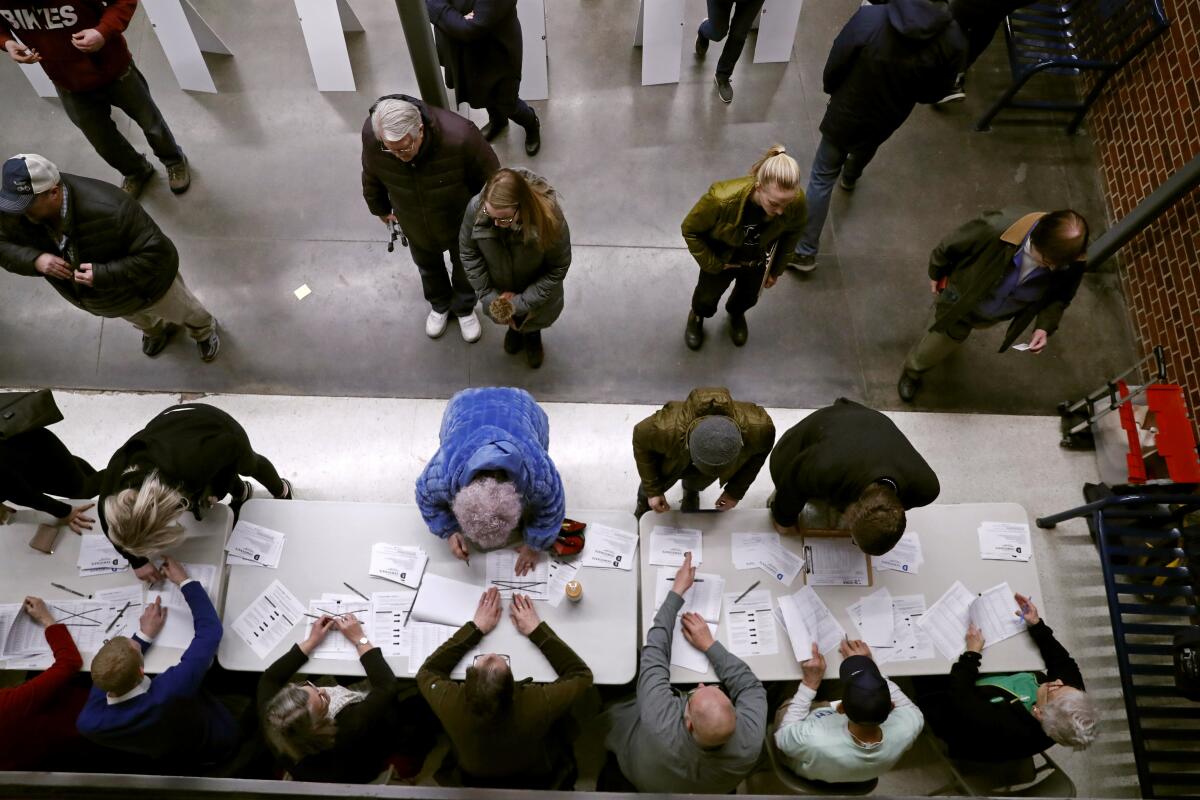

As the place where the first voting of the 2020 campaign was held, the state was supposed to add clarity to the Democratic contest by thinning the field and hinting at the direction — ideological, generational — voters wished to pursue.

Instead, it compounded the confusion and unleashed a fresh round of finger-pointing and acrimony.

Candidates and their supporters were furious at the Iowa Democratic Party for its handling of the results. Iowa Democrats were angry at the national party for insisting on new ways of reporting the outcome.

Opponents of Sanders blamed him for the mess, noting he demanded changes after losing Iowa to Hillary Clinton. Backers of Sanders accused the party establishment of plotting once more to thwart him.

For many Democrats, it was a worrisome sign of unraveling at a time they hoped to start narrowing their choices to determine who could best take on President Trump.

“Democrats need to take a long, hard look at what happened,” said Carrie Giddins, a professor of political writing at American University and a veteran of two Democratic campaigns in Iowa. “If we don’t learn from last night, from low turnout to the computer debacle, we have the potential to be in trouble for November.”

Not surprisingly, Trump and fellow Republicans took glee in the upheaval, suggesting the breakdown was symptomatic of the party’s larger failings. “The Democrat Caucus is an unmitigated disaster,” the president tweeted. “Nothing works, just like they ran the Country.”

With no clear winners, or losers, candidates stepped into the vacuum and sought to use the disarray to their advantage.

After Iowa’s caucuses fail to winnow the Democratic field, New Hampshire’s Feb. 11 primary is even more important, and candidates flock to the state.

Before the party issued its partial returns, the Sanders and Buttigieg campaigns released their own favorable tabulations. Tom Steyer, the billionaire political activist, could hardly suppress a broad grin on MSNBC even as he acknowledged “the system had a very bad night.”

Although he finished far back in Iowa’s partial returns, he said the race had cracked “wide open.”

While the candidates moved on to New Hampshire, which holds the first primary next Tuesday, Iowa Democrats struggled to figure out what went wrong and deal with the aftermath.

“It is horrific. It is embarrassing,” said Kurt Meyer, the Democratic Party chairman for three rural counties in northern Iowa. “I know a lot of people across the country and I have gotten lots of emails, lots of texts, lots of calls, lots of Facebook messages saying what the hell is going on?”

At a brief news conference Tuesday, state chairman Troy Price apologized, said the counting delay was “unacceptable” and committed to an independent review.

In a rare show of bipartisanship, the state’s Republican governor and two U.S. senators joined Democrats in defending the state’s privileged place at the start of the campaign calendar, which has served Iowa tremendously well, both economically and politically, for nearly half a century.

“It’s an entire industry, not just a political event,” said Craig Robinson, a GOP strategist who helped run the 2008 Republican caucuses. “I’m afraid we might have seen the end of it. It’s always a fight to keep it, even when we nail it.”

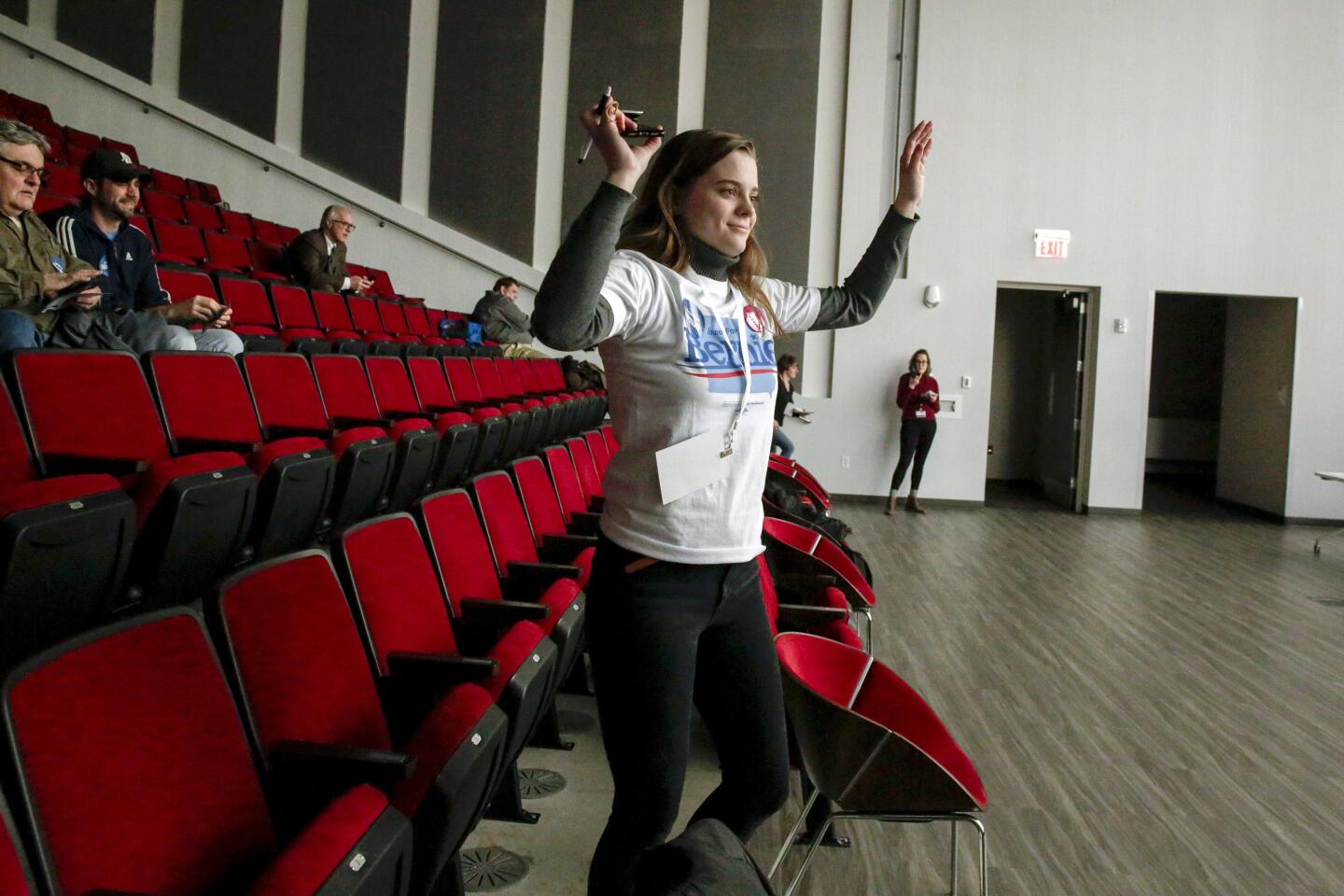

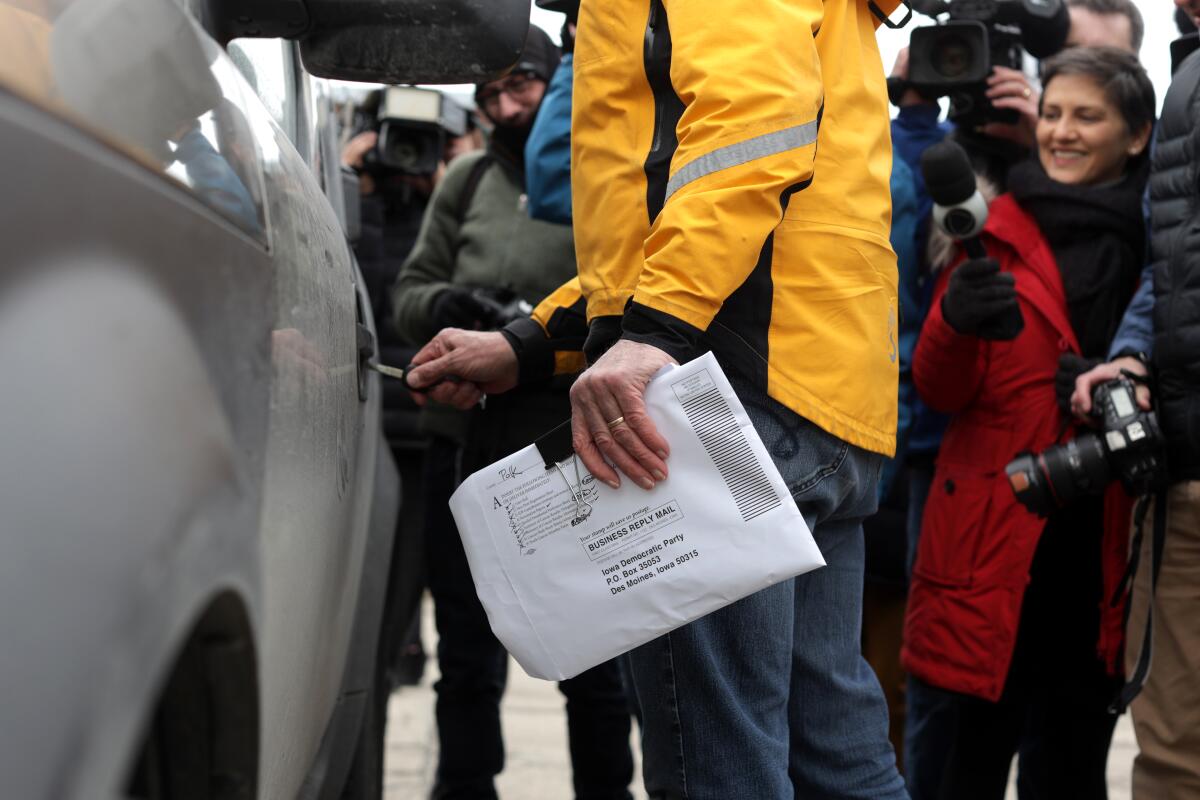

At the center of the mishap was a computer application intended to help tally results, which will apply toward allocating delegates to the summer’s national nominating convention. Democrats throughout the state reported problems working with the app and difficulty phoning in results.

In Nevada, which will hold its own caucuses on Feb. 22, after the New Hampshire primary, party leaders insisted Iowa’s troubles would not be repeated, though the formula for determining the winner is far more complex than the one used here.

“We will not be employing the same app or vendor,” Democratic Chairman William McCurdy II said. “We had already developed a series of backups and redundant reporting systems, and are currently evaluating the best path forward.”

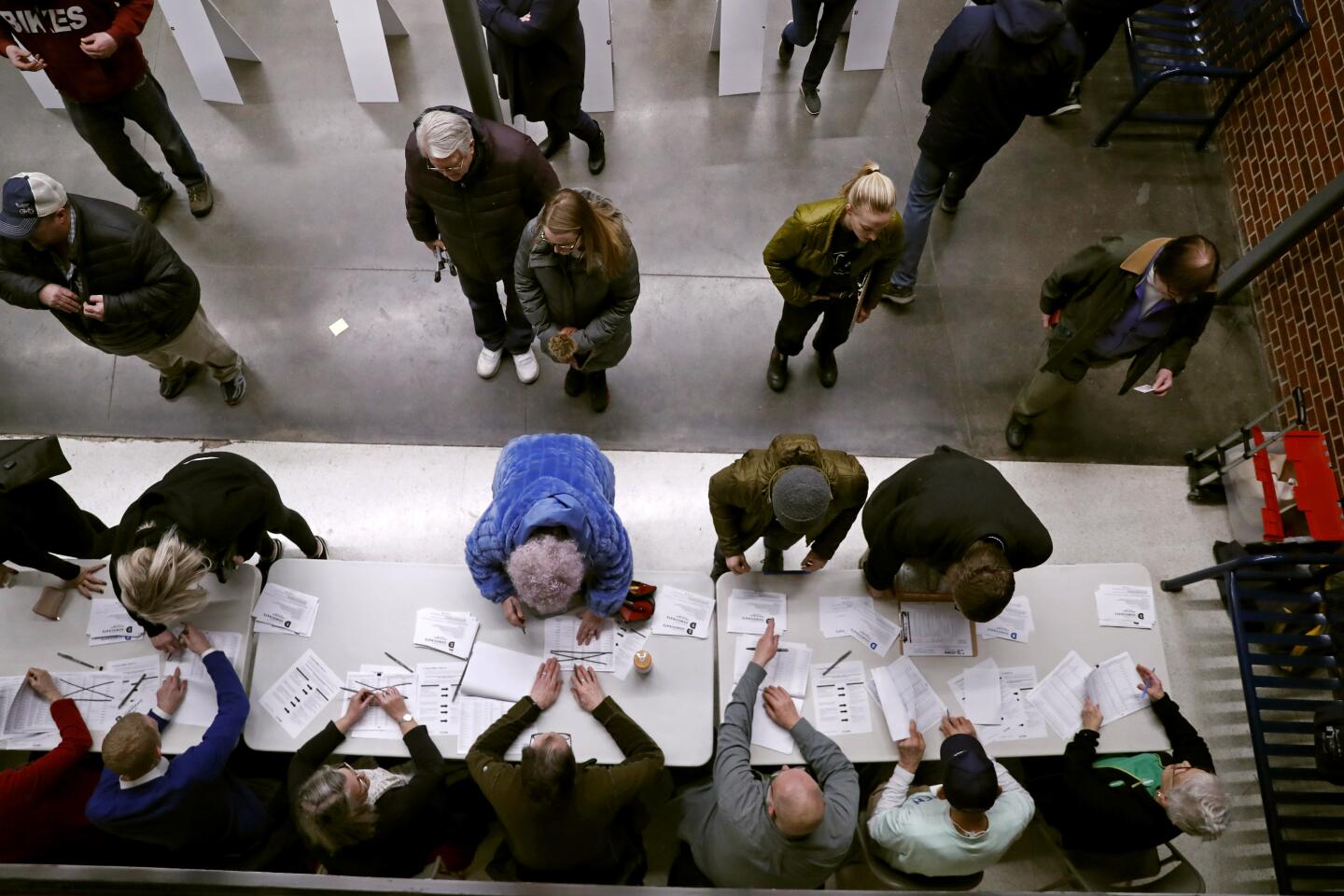

Iowa party officials were required to report three sets of numbers: how many people supported each candidate, how many supported each candidate once laggards were dropped and voters realigned, and the number of delegates each candidate netted.

“What happened is partly our fault,” said Dave Nagle, a former congressman and Iowa Democratic Party chairman, who has spent nearly 40 years defending the caucuses. “But part of the fault lies with the [Democratic National Committee]. The DNC asked to us to do more than we could and we foolishly agreed to do it so we could stay first.”

Unlike elections run by government officials, the caucuses are staffed by volunteers. The more complex reporting system appeared to overwhelm many of them, and spotty cellphone service contributed to the problem.

John Grennan, co-chairman of the Poweshiek County Democrats, said the difficulties were no surprise given the trials beforehand.

“They had all these issues,” Grennan said. “We were supposed to be getting invitations to use it. The invites would never arrive.” The communications that Grennan did receive were confusing, he said.

Others leading their caucuses reported error messages when attempting to upload results; some were unable to get the app installed at all.

Compounding the anger at Iowa — a perennial target of jealousy for its early-voting position — was the troubled history of recent caucuses.

In 2012, Republicans wrongly crowned Mitt Romney the victor on caucus night. More than two weeks later, former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum was declared the winner, but by then Romney was on his way to the nomination.

Four years later, Democratic Party leaders were unable to track down tallies in several precincts, meaning they could not officially name Clinton the winner until more than half a day after the caucuses ended.

Iowans are used to attacks on the caucuses, but many were resigned to finally losing the fight and surrendering the lead-off role when the balloting begins in 2024.

Dennis Goldford, a Drake University political scientist who has written extensively about the caucuses, suggested all may not be lost.

“Forty-eight states dislike the position of Iowa and New Hampshire,” he said. “But until they can agree on which would replace them in the process,” it may be difficult to elbow either aside.

Times staff writer Jeff Bercovici in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.