Trump administration takes steps to close border to migrants, citing coronavirus

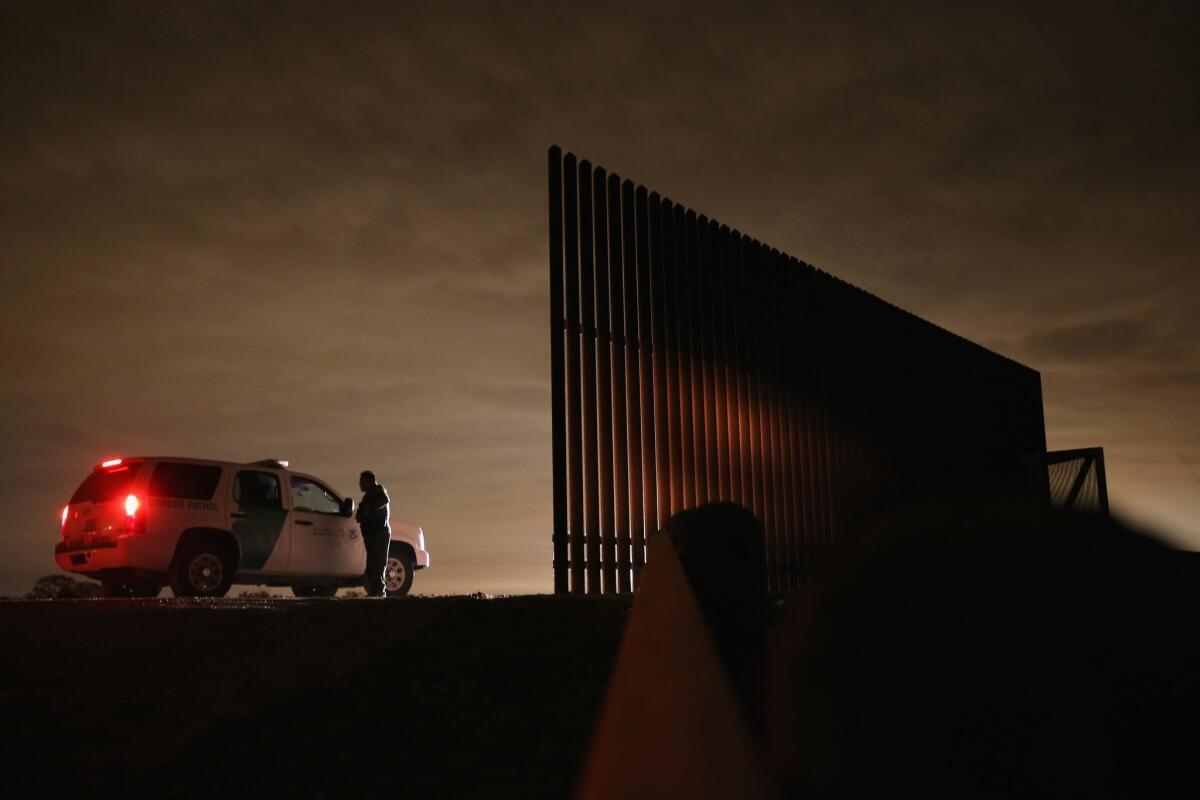

The Trump administration is taking steps to close the southern border to certain migrants, citing the rapid spread of the coronavirus.

U.S. immigration authorities could soon begin immediately removing migrants who enter the U.S. between official ports of entry and turning them back to Mexico, saying it will help stanch the expansion of the pandemic, officials told The Times.

The administration has yet to formally announce the proposal, first reported by the New York Times on Tuesday night, but it is hammering out final details. Earlier Tuesday, administration officials began laying the groundwork for the shift.

Under the new policy, Border Patrol agents who apprehend Mexican adults attempting to cross the border between ports of entry will return them to Mexico at a nearby port of entry instead of detaining them, according to Brandon Judd, president of the union that represents 15,000 agents, the National Border Patrol Council.

Agents will have to check migrants’ information, including criminal records, in the field. Equipment to help them perform those checks was already being distributed Tuesday, Judd said.

Judd, who is close to the Trump administration, added that the new policy could take effect as soon as Tuesday night.

“This will greatly limit the potential for spread of the coronavirus,” he said. “The administration was looking at ways to minimize exposure.”

The administration also began recalling asylum officers and other employees of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services — the arm of the Homeland Security Department that administers the legal immigration system — from detention facilities and postings across the country on Tuesday.

ICE agents given masks for protection. Children at homes they door-knock. Eerily quiet neighborhoods. A day in the life of ICE agents seeking to make arrests in the age of coronavirus

While some asylum screenings will continue telephonically, other immigration interviews have been canceled until April 1, agency sources told The Times on condition of anonymity, to protect against professional retaliation. Earlier Tuesday, the agency canceled all in-person services and shuttered offices.

Yet confusion abounded Tuesday night, as officials charged with implementing the proposal remained unclear as to its details.

Before the global outbreak of the coronavirus, U.S. officials already had been swiftly removing many migrants, and forcing many asylum seekers back to Mexico — or other countries farther south — under other policies designed to deter migration to the southern border. And this would not be the first time that President Trump has threatened to close the southern border.

Homeland Security and White House officials declined to confirm the plan regarding its coronavirus response, or provide more clarity.

“President Trump is one hundred percent focused on protecting the American people from the Cornavirus and all options are on the table,” Homeland Security Department spokeswoman Heather Swift said in a statement.

If enacted, the proposal is also likely to face immediate legal challenges.

Judd said the policy would not apply to families, children or Central American migrants, who can only be returned to Mexico with the Mexican government’s approval, while other publications reported that all migrants apprehended between ports of entry, regardless of nationality, would be returned to Mexico.

Neither U.S. Homeland Security Department officials nor Mexico’s immigration institute responded to questions as to whether Mexico has been informed that the U.S. intends to unilaterally return migrants to its territory, without any screening or, reportedly, whether or not they are Mexican citizens.

It also was not immediately clear Tuesday whether asylum seekers, who have a legal right to seek protection in the United States wherever they enter, will be allowed to begin the process during this time, though the pullback of asylum officers indicated that applications could be curtailed.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

The U.S. has exponentially more coronavirus cases than Mexico and most every other country to the south in the Western Hemisphere. Trump administration officials also have yet to confirm that any Homeland Security employees in the government’s third-largest agency — or any migrants in its detention facilities — have the coronavirus.

Judd said that so far, no agents or detained migrants have tested positive. He acknowledged that there have been far fewer cases reported in Mexico than in the U.S., but he said there’s still concern the virus could spread from Mexico.

The White House also has resisted calls to cease interior immigration enforcement, stop immigration court proceedings or release any migrants from detention facilities that are highly vulnerable to the spread of the pandemic, despite concerns from Trump administration and other regional officials, health experts and immigration advocates that the government is risking worsening the spread of coronavirus within the United States or to other countries.

Earlier Tuesday, Guatemala became the first nation to refuse U.S. deportation flights, either of Guatemalans or of other citizens under a controversial asylum agreement with the Central American nation. Under that agreement, since November the U.S. has sent more than 900 Hondurans and Salvadorans seeking asylum in the United States to Guatemala instead.

Homeland Security authorities such as David Marin, the director of enforcement and removal operations for Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Los Angeles, had expressed concerns that if other countries refused to accept deportation flights amid coronavirus fears, detention space in the United States might soon fill up. At Adelanto detention center in California, for example, Marin said, if officials can’t remove 150 people per week — about half of whom typically are Mexican citizens whom authorities drive to the border — they’d be at maximum capacity in roughly two weeks.

Under a court decision, people can’t be held in custody longer than 180 days once they have a final order for removal if there’s not a significant likelihood of removal in the foreseeable future.

“Mexico won’t be far behind,” Marin said. “If we had somebody and this went on for more than six months, we’d have to revisit every single one of those cases. We’d get backed up.”

As of last Thursday, Immigration and Customs Enforcement began taking the temperature of detainees placed on a plane to be deported to another country, officials told The Times. They have done the same for those getting on a flight to be transferred to another detention center.

Marin rejected the criticism that by continuing enforcement amid the coronavirus, the agency could endanger the public and migrants in their custody.

He asked, “So every detention center, every place where you’re keeping people in close proximity, jails, prison, should just release people?”

Eleanor Acer, director of refugee protection for Human Rights First, said the Trump administration is using the coronavirus as a cover for its clearly stated goals of restricting immigration.

“Decisions relating to the pandemic should be guided by public health officials,” Acer said in a statement, “not by the Trump Administration’s long-standing agenda to close the border to refugees seeking asylum.”

O’Toole reported from Guatemala City, Hennessy-Fiske from New Orleans. Times staff writer Brittny Mejia in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.