News Analysis: Biden’s convention leans heavily to the center, with muted outcry from the left

WASHINGTON — The first night of the Democratic convention featured John Kasich, the Republican former governor of Ohio, seeking to reassure members of his party that if they voted for Joe Biden, he would not “turn sharp left and leave them behind.”

On the second night, former GOP Secretary of State Colin Powell, former Republican Defense Secretary and Sen. Chuck Hagel and other stalwarts of the traditional foreign policy establishment saluted Biden as a leader who would, in Powell’s words, “stand with our friends and stand up to our adversaries.”

On Wednesday, while the night’s speakers stuck to a more consistently Democratic script, prominent liberal Jesuit priest Father James Martin pledged that in his benediction on the convention’s following and final night, he would mention the “unborn” — a word rarely heard at recent Democratic conclaves.

“These are not normal times,” as Kasich said.

But more surprising than some of the words from the convention’s virtual podium has been the reaction from the Democratic left — not quite a collective shrug, but something far short of rebellion.

Republican spokespeople see the relative quiet on the left as evidence of a devious charade. President Trump, having oscillated for weeks among a contradictory mix of attack lines against Biden, has recently settled on the accusation that the former vice president is a “puppet” being manipulated by “radical Democrats” like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the progressive member of Congress from the Bronx whose speaking time at the convention was limited Tuesday to about 90 seconds.

But among some Democrats, the prevalence of current and former Republicans at this week’s convention has given rise to a revival of an old political phrase.

Jeff Weaver, a top advisor to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, illustrated the revived coinage. “What Vice President Biden has been able to demonstrate is the breadth of his electoral coalition, the formation of a popular front” against Trump, he said.

The label “popular front” first gained currency in France and Spain in the 1930s as parties on the left formed alliances to confront the rise of fascism. Its sudden popularity among Democrats speaks to the concern many in the party have about how “authoritarianism has taken root in our country,” under Trump, as Sanders said in his speech Monday night.

The popular front idea also helps explain the tolerance on the left for the extensive courtship of the other side of the aisle.

Not everyone is fully on board, of course: The specter of another four years of Trump has not caused Democrats to entirely abandon their party’s devotion to disagreement.

“The Republican leadership, for all of its scapegoating, racism and xenophobia, knows how to play to its base to get out the vote,” said Marcy Winograd, a Sanders delegate and co-founder of the Los Angeles chapter of Progressive Democrats of America.

“I would urge the DNC to remember its base and not deflate delegates with speeches from Republicans who led us into war on Iraq or signed legislation to restrict reproductive rights,” Winograd said.

David Sirota, a former aide to Sanders known for intense attacks on moderates in the party, wrote an essay Wednesday saying that he still intended to vote for Biden but denouncing the convention’s “incessant demand to be happy about fraudulence.”

So far, however, the vocal objectors remain in the minority.

In polling, “well north of 90% of Sanders supporters are backing Biden” at this point, said Bob Shrum, the veteran Democratic strategist who directs USC’s Center for the Political Future.

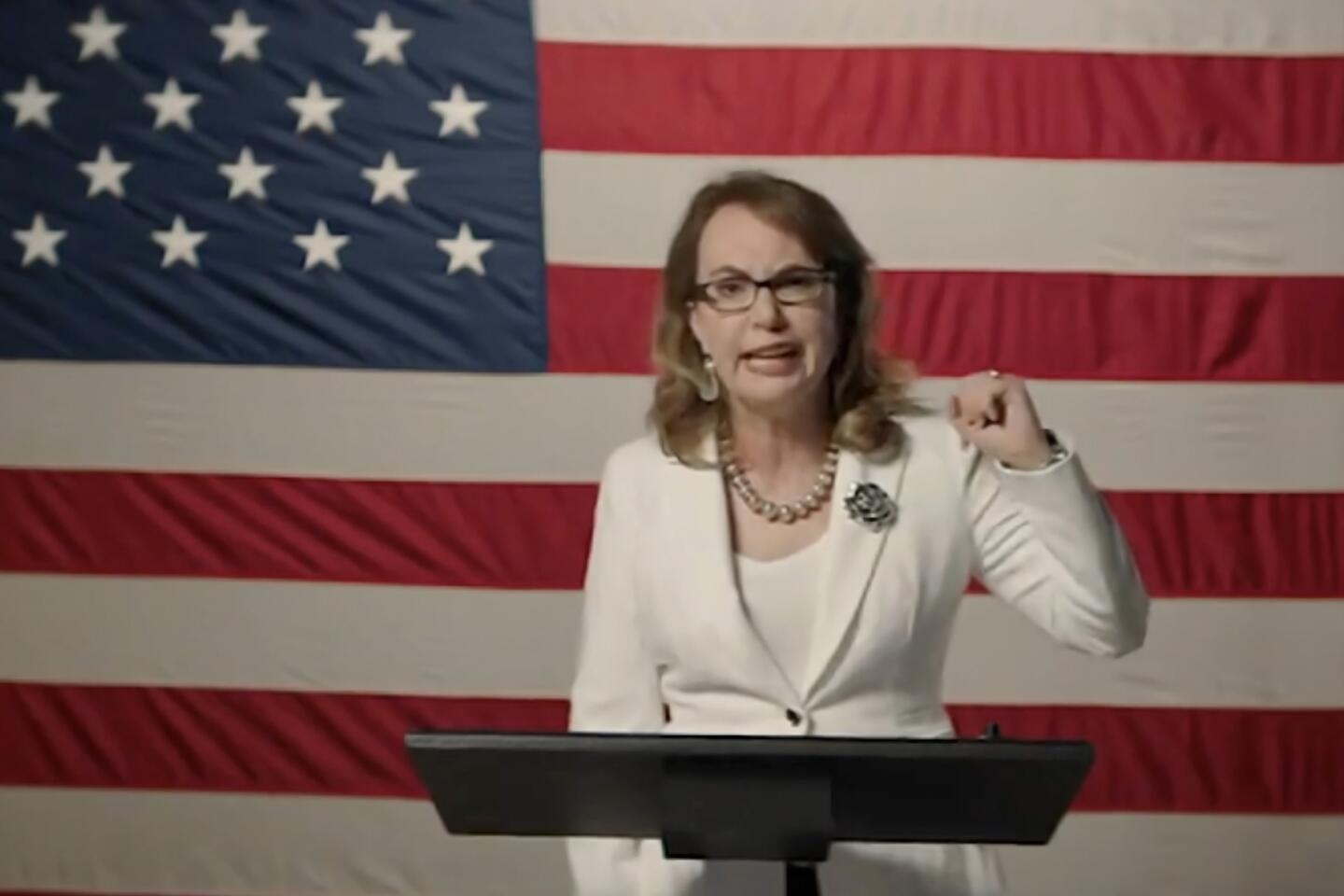

President Trump and Joe Biden couldn’t be further apart on gun policy. One says he ‘saved the 2nd Amendment,’ the other pushes for gun control measures.

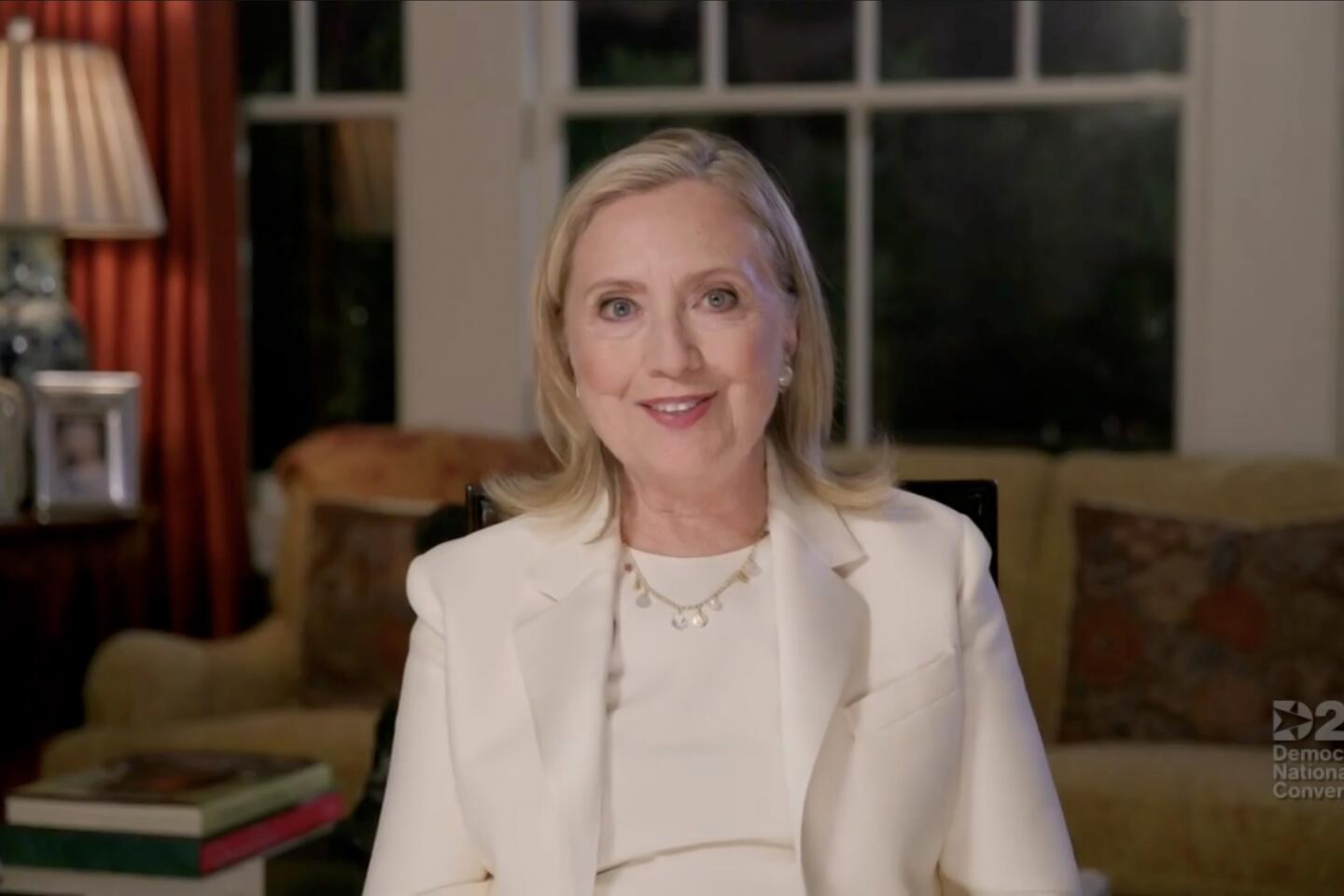

Biden and his campaign aides have had remarkable success in unifying Democrats, said Democratic analyst Ruy Teixeira. In sharp contrast to four years ago, when Democrats remained deeply divided between supporters of Sanders and backers of Hillary Clinton, Biden spent the late spring and summer successfully mending relations, following the principle of “not making anybody your enemy unless they need to be,” Teixeira said.

Weaver, who was deeply involved in the intraparty negotiations both this time and four years ago, said that the way Biden’s camp “reached out and worked” to forge agreements with Sanders on much of the party platform leaves him with “no concerns.”

The efforts to attract support from people like Kasich are part of building “an electoral coalition; it’s not the governing coalition,” he said.

“We certainly have seen no backsliding on the substance” of the issues that the Biden and Sanders camps agreed to, he added.

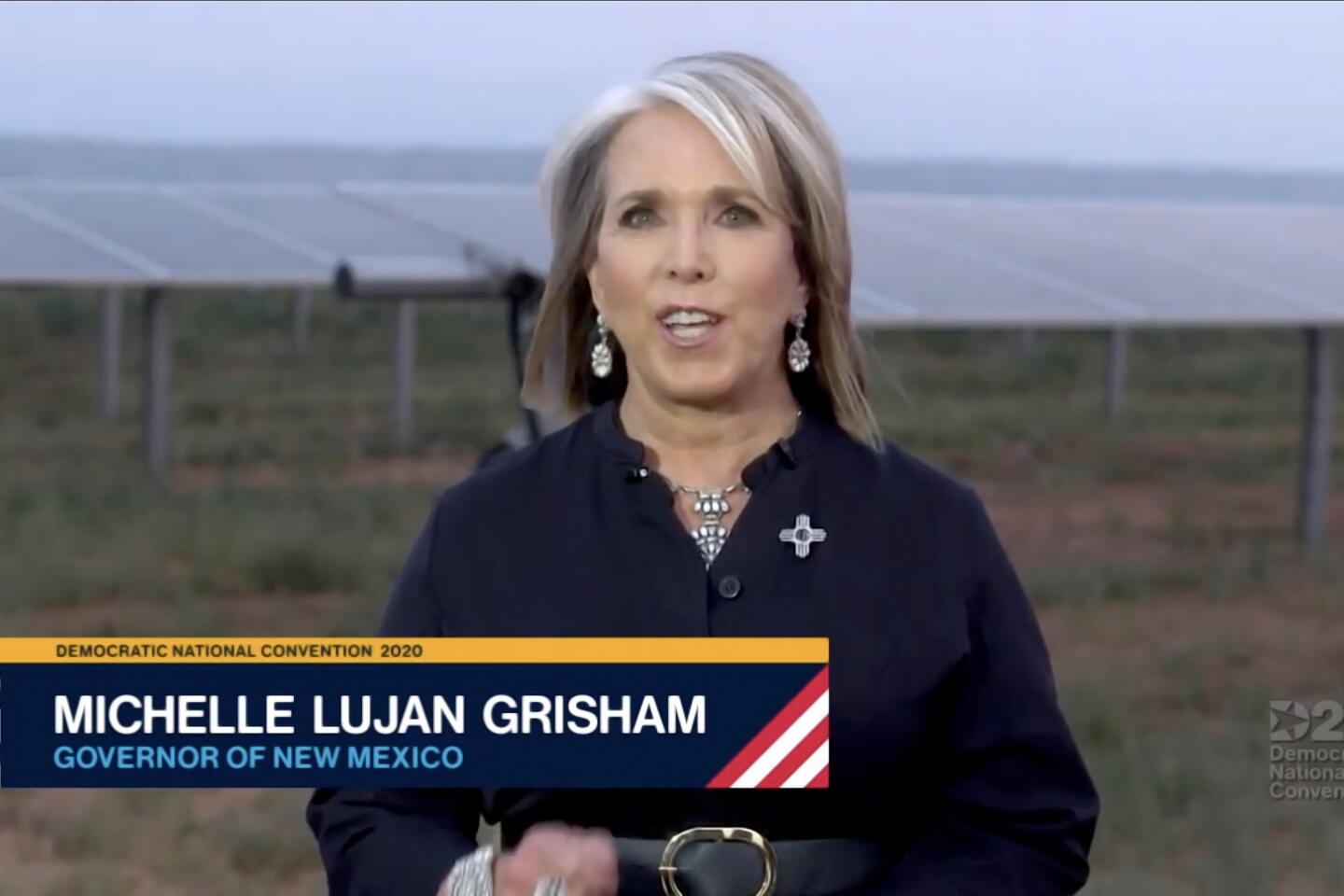

Those negotiations led to agreements on some positions that might fit Kasich’s definition of a “turn sharp left,” including an increase in the minimum wage to $15 per hour, support for paid family leave and a plan to combat climate change by ending the burning of oil, coal and other fossil fuels for electricity by 2035. Biden also supports a proposal ardently sought by progressives to revive and expand parts of the Voting Rights Act that were struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013.

On other issues, the party remains more divided: Most notably, Biden during the primaries rejected Sanders’ signature call for abolishing private health insurance and moving to a single-payer, “Medicare for all” plan. Biden’s alternative, however, a public option plan that would allow people to enroll in government health insurance if they want it, would go far beyond what the Obama administration proposed during the legislative battles over healthcare in 2009 and 2010.

Biden also opposes calls to defund police departments, an idea pressed by many Black Lives Matter activists.

“If he gets elected, there’s still a real potential problem” of sharp clashes between Biden and the left on those and other topics, Teixeira said.

There’s also the issue of whether bipartisanship as Biden envisions it — or at least often talks about it — would work as a governing strategy.

Although the list of Republicans endorsing Biden has grown long, it hasn’t grown in currency: Nearly all have in common that they no longer hold public office. The Republicans who do hold office increasingly share — or at least mouth — Trump’s views.

Joe Biden has made much of his ability to reach across the partisan divide, but the gap has widened since his years as a senator, and since Trump.

For now, however, those problems lie in the future. The Democrats’ moderate establishment and progressive insurgents both seem willing to set them aside in the interest of not just mobilizing the party’s base, but of winning over voters who four years ago sided with Trump or with third-party candidates.

“We want white, working-class voters; we want older voters,” Teixeira said.

And even Democrats who dislike seeing Republicans share their stage seem willing to put up with it.

Henry Huerta, another Sanders delegate from California, called the presence at a Democratic convention of Republicans like Meg Whitman, the GOP’s candidate for California governor in 2010, “a difficult pill to swallow.”

“The only issue that they agree with us on,” he said, “is disliking Donald Trump.”

Times staff writers Melissa Gomez and Seema Mehta in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.