President Trump could learn, but probably won’t, from these past concession speeches

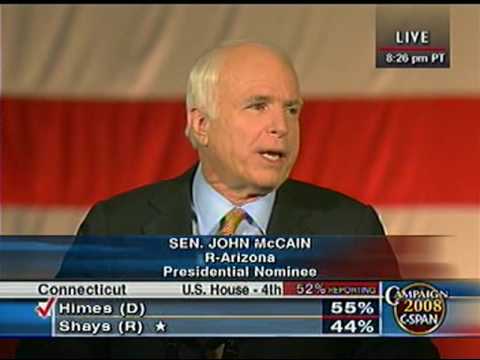

In this video from Nov. 4, 2008, Sen. John McCain concedes the 2008 presidential election to Barack Obama.

For more than a century, a routine of American democracy has been a public concession by losing presidential candidates. The message varies in all particulars except one: the vanquished calling on the country to unify behind the new president.

The 124-year tradition appears in peril in 2020, as President Trump — standing on the precipice of defeat — signals his determination to lead a protracted campaign to reverse the likely victory by former Vice President Joe Biden.

“I easily WIN the Presidency of the United States with LEGAL VOTES CAST,” Trump claimed via Twitter early Friday, one of a string of contentions by the president and his followers that was unsupported by substantial evidence.

It was not a new message from a president who has been signaling for months that he might not accept the result of the election he has worked to delegitimize.

“I’m not a good loser. I don’t like to lose,” Trump told Fox News host Chris Wallace in July. “I don’t lose too often.”

Wallace followed up, “But are you gracious?” To which Trump responded: “You don’t know until you see. It depends.”

This is not the norm.

Most incumbents and presidential aspirants say they respect and will honor the electoral process, though there have been challenges of razor-tight contests. There is not a precedent in modern times for a candidate suggesting an election was rigged.

The speeches are no small matter, said presidential historian Robert Dallek, because they “demonstrate a continuing commitment to peaceful transitions of power.”

Dallek, who has written about presidents dating to Franklin D. Roosevelt, said the messages also send an important “signal to supporters that they need to join the defeated candidate in accepting the loss.”

Brushing aside polls showing his support down amid the worsening coronavirus outbreak, Trump won’t promise to accept the 2020 election result.

As far back as 1896, losers have accepted defeat publicly, usually with haste and most often with professions (at least publicly) of support for the winner.

Democrat William Jennings Bryan lost that last contest of the 19th century, sending a telegram to Republican William McKinley: “I hasten to extend my congratulations. We have submitted the issue to the American people and their will is law.”

In each of the 30 contests that followed, the losers let the world know — first by public speech, then by movie newsreel, then radio address and, finally, on live television — that the campaign had ended and the other side won.

While public addresses are not required, they have become custom, along with their archetypal contents: acknowledging defeat, congratulating the victor, urging the country to unify for the common good and suggesting the vanquished combatant will continue to fight for the causes they believe in.

Over the decades, the defeated occasionally have sounded profound notes of grace.

In 2008, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) acknowledged before a crowd outside a Phoenix hotel that the American people had “spoken clearly” in electing Sen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.). He waved off those in the crowd who shouted, “No!”

Images from Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia and Nevada show 2020 election unrest.

“This is an historic election,” he said, as Obama became the first Black man elected president. “And I recognize the special significance it has for African Americans and for the special pride that must be theirs tonight.”

In a speech written by his longtime aide and biographer, Mark Salter, McCain said it was time for the country to move beyond the scourge of racism and to unite.

“I urge all Americans who supported me to join me in not just congratulating him, but offering our next president our goodwill and earnest effort to find ways to come together,” McCain said, “to find the necessary compromises, to bridge our differences and help restore our prosperity, defend our security in a dangerous world, and leave our children and grandchildren a stronger, better country than we inherited.”

McCain called the 2008 campaign “the great honor of my life” and added, “My heart is filled with nothing but gratitude for the experience and to the American people for giving me a fair hearing before deciding that Sen. Obama and my old friend, Sen. Joe Biden, should have the honor of leading us for the next four years.”

Eight years later Hillary Clinton was on the short end of Trump’s stunning upset victory. She called Trump on election night to concede and made a public speech the following day.

“I hope that he will be a successful president for all Americans,” said the former secretary of State and U.S. senator.

After urging the women and girls who supported her, in particular, to keep dreaming about electing a woman to the White House, Clinton described the beauty of America’s peaceful transfers of power.

Excerpts of her concession speech Wednesday in New York This is not the outcome we wanted or we worked so hard for, and I’m sorry that we did not win this election for the values we share and the vision we hold for our country.

“Donald Trump is going to be our president. We owe him an open mind and the chance to lead,” Clinton said. “Our constitutional democracy enshrines the peaceful transfer of power. We don’t just respect that. We cherish it.”

The most dramatic concession in modern times came in 2000, when the election came down to Florida, where ballots were counted for weeks after election day. It was not until Dec. 12 that the U.S. Supreme Court ordered an end to the ballot count, making Texas Gov. George W. Bush a 527-vote victor over Vice President Al Gore.

Gore initially called Bush on election night and conceded, only to call less than an hour later, saying he had been premature, given the razor margin in Florida. A tense exchange between the two men followed.

Thirty-six days after the election, Gore faced television cameras and cut the high tension with a joke.

“Just moments ago, I spoke with George W. Bush and congratulated him on becoming the 43rd president of the United States,” Gore said. “And I promised him that I wouldn’t call him back this time.”

He offered to meet with Bush “as soon as possible so that we can start to heal the divisions of the campaign and the contest through which we’ve just passed.”

Gore then cited a precedent from an era even before public concessions to evoke the spirit of e pluribus unum.

“Almost a century and a half ago, Sen. Stephen Douglas told Abraham Lincoln, who had just defeated him for the presidency, ‘Partisan feeling must yield to patriotism. I’m with you, Mr. President, and God bless you.’ ”

For a less statesmanlike approach, a pre-presidency Richard Nixon might be the model. In 1962, he conceded he had lost the race for governor of California to Pat Brown.

In a long and rambling speech, Nixon wove together conciliation with recrimination. He wished Brown well but added: “I believe Gov. Brown has a heart, even though he believes I do not. I believe he is a good American, even though he feels I am not.”

The speech ended with a long disquisition on the failures of the press, culminating with a famous zinger: “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.