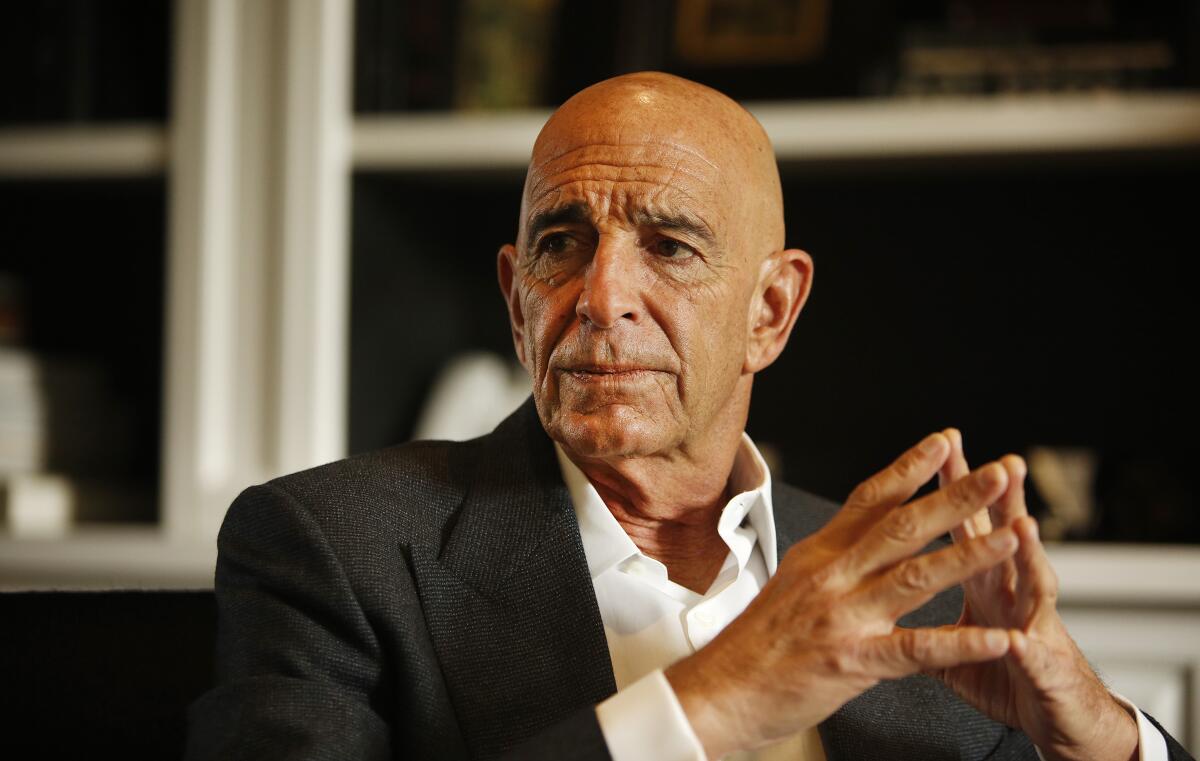

Tom Barrack, L.A. investor and Trump ally, charged with acting as agent of UAE

Thomas J. Barrack, Jr., the chair of former President Trump’s inaugural committee and a prominent Southern California businessman, was arrested Tuesday on federal charges that he and two associates were part of a secretive, years-long effort to shape Trump’s foreign policy as a candidate and later, president, all to the benefit of the United Arab Emirates.

Barrack, 74, and the two other men were indicted in a New York federal court and accused of acting as unregistered foreign agents of the wealthy Persian Gulf state starting about the spring of 2016.

The indictment said four UAE officials “tasked” Barrack and his associates with influencing public opinion through media appearances; molding the foreign policy positions of the Trump campaign and later, the Trump administration; and developing “a back-channel line of communication” with the U.S. government that promoted Emirati interests.

Barrack was also accused of obstructing justice and making several false statements in a 2019 interview with federal agents, when he denied being asked to acquire a phone dedicated to communicating with Middle Eastern officials.

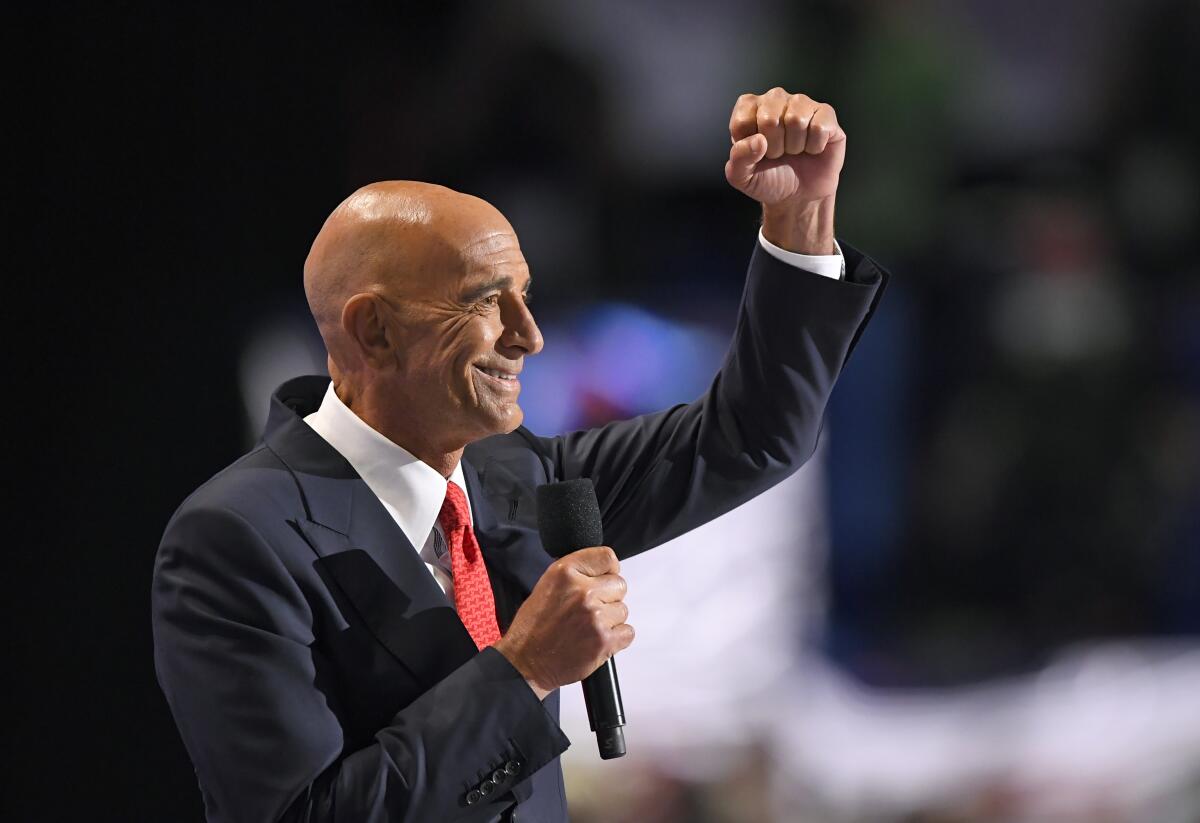

The indictment alleges Barrack’s work had a direct impact on Trump’s behavior, including a 2016 speech when Trump pledged work with “our Gulf allies” and a phone call the president had with an unidentified UAE leader. Barrack also wrote an op-ed published in Fortune magazine that relied on feedback from UAE officials and made numerous television interviews promoting their national interests.

After a July 2016 television appearance in which Barrack repeatedly praised the UAE, he messaged another man named in the alleged conspiracy, boasting, “I nailed it ... for the home team.”

Barrack was arrested Tuesday morning at an unidentified business site in Sylmar, according to an FBI spokeswoman. During an initial appearance Tuesday afternoon at a downtown L.A. federal court, Barrack appeared remotely from a different federal courthouse, also downtown, but thick wire mesh obscured his face.

U.S. Magistrate Patricia Donahue ordered Barrack detained pending a hearing Monday, in accordance with an agreement reached by prosecutors and defense attorneys.

“Mr. Barrack has made himself voluntarily available to investigators from the outset,” said a statement issued by Barrack’s spokesperson. “He is not guilty and will be pleading not guilty.”

A congressional report identified investor Tom Barrack as a key figure in a raft of initiatives that “virtually obliterated the lines normally separating government policymaking from corporate and foreign interests.”

In announcing the high-profile prosecution, federal officials blasted Barrack and the two other defendants, Matthew Grimes, 27, of Aspen, Colo., and a UAE national, Rashid Alshahhi, 43, for participating in the alleged conspiracy to sway the decisions of the Trump campaign and administration.

“The defendants repeatedly capitalized on Barrack’s friendships and access to a candidate who was eventually elected president, high-ranking campaign and government officials, and the American media to advance the policy goals of a foreign government without disclosing their true allegiances,” acting Assistant Atty. Gen. Mark Lesko said in a statement.

He added: “The conduct alleged in the indictment is nothing short of a betrayal of those officials in the United States, including the former president.”

Grimes was arrested at a home in Santa Monica, and an attorney for him could not be reached for comment. At a court appearance Tuesday, Grimes was deemed a flight risk and detained at least until a Monday hearing.

A prosecutor said in court Tuesday that Alshahhi left the U.S. in 2018 after an interview with federal agents; he remains at large.

A spokeswoman for Trump did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The grandson of Lebanese Christian immigrants, Barrack grew up in Culver City and graduated from USC, where he remains a trustee and frequent campus guest. After college, Barrack parlayed a project in Saudi Arabia into advising the royal family, and since the 1970s, he’s cultivated deep ties across the Middle East, including friendships with the leaders of Qatar and the UAE, as well as a three-decade friendship with Trump.

Barrack founded Colony Capital, a publicly held investment firm, and has amassed a net worth of about $1 billion, according to Forbes.

Barrack relied on his status as a well-connected Middle Eastern courtier and Trumpworld insider to illegally — and covertly — further UAE’s foreign policy aims, the indictment said.

As the global recession deepened in 2008, Tom Barrack was in his element.

Barrack capitalized on his close ties to Trump, including influencing a speech about energy issues that was delivered on May 26, 2016, according to the indictment. Trump, then seeking the Republican nomination, pledged in the speech that the U.S. would “work with our Gulf allies.”

After the speech, the indictment said, an unnamed Emirati official emailed Barrack to say “congrats on the great job today” and that “everybody here are happy with the results.”

After Trump defeated Hillary Clinton and became president-elect, Barrack assumed the role of chair of the inaugural committee, raising more than $100 million for the fete from well-heeled supporters and corporate interests.

Barrack also traveled to the UAE with Grimes, who worked at Colony Capital, and they met with Alshahhi and other Emirati officials, according to the indictment. In a meeting there, Barrack conveyed a plan to influence U.S. foreign policy over the next 100 days, six months, year and four years, the indictment details.

Afterward, Alshahhi conveyed to Grimes that officials were “very happy here,” and Alshahhi later told an Emirati official that Barrack would “be with the Arabs.”

Soon after Trump took office, Barrack allegedly ensured that the new president connected over the phone with a UAE leader. Grimes later said that “we can take credit for phone call,” the indictment said.

Alshahhi also sent Grimes the résumé of a congressman that UAE officials hoped would be their next U.S. ambassador. The unnamed congressman’s appointment “was very important for our friends,” Alshahhi advised Grimes, according to the indictment. Alshahhi pushed the nomination of the same congressman to Barrack days later, telling him, “Your help will go long way.”

There followed correspondence and strategizing about the next ambassador, with Barrack at one point mentioning he could be named ambassador or a special envoy to the Middle East. Barrack allegedly said that his appointment “would give Abu Dhabi more power!”

“This will be great for us. And make you deliver more. Very effective operation,” Alshahhi replied to Barrack. No such position ever materialized.

Taken together, the text messages and emails show the trust that UAE officials had in Barrack and his success at navigating an administration that was freewheeling and turbulent during Trump’s first year in office.

The case against Barrack is a reminder of how deeply foreign interests penetrated Trump’s inner circle. Michael Flynn, Trump’s first national security advisor, admitted to working on Turkey’s behalf while serving on Trump’s campaign in 2016. Paul Manafort and Rick Gates, top campaign officials that same year, confessed to acting as unregistered lobbyists for Ukraine.

Imaad Zuberi, a top California fundraiser, admitted funneling foreign money into campaigns of Republicans and Democrats alike.

More recently, Rudolph W. Giuliani, Trump’s lawyer during the former president’s attempt to overturn his election defeat, has been under investigation for his own foreign entanglements. Federal investigators searched his apartment and office and seized his electronic devices in April as part of an investigation into whether he had violated the same lobbying law, known as the Foreign Agents Registration Act.

The law requires people to disclose when they’re lobbying on behalf of a foreign government, and the Justice Department stepped up its enforcement during the special counsel investigation into Russia interference in the 2016 election.

Times staff writer Chris Megerian in Washington, D.C. contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.