After recall flop, struggling California Republicans once again fighting over future

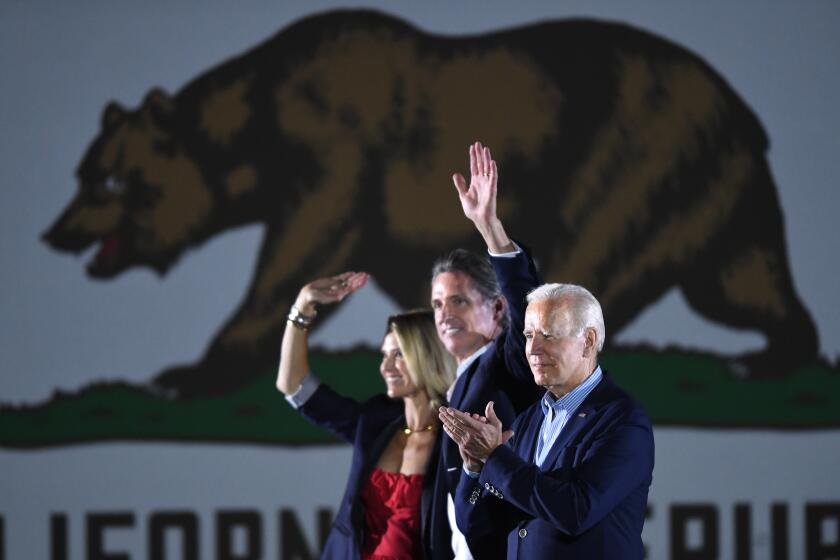

California Republicans thought they found a unifying rallying cry in the recall attempt against Gov. Gavin Newsom. Instead, the campaign exposed — and even worsened — some of the long-standing clashes between the establishment and grass-roots base, while leaving unsettled the question of how the party can stop its losing streak in the state.

The GOP can take comfort in knowing it made Newsom sweat far more than any Democrat has in the last decade of statewide races, at least until the polls closed and the governor easily prevailed.

The lopsided outcome underscores how the party’s daunting climb back to political relevance is made all the more difficult by the recall effort’s missed opportunities and internecine squabbles.

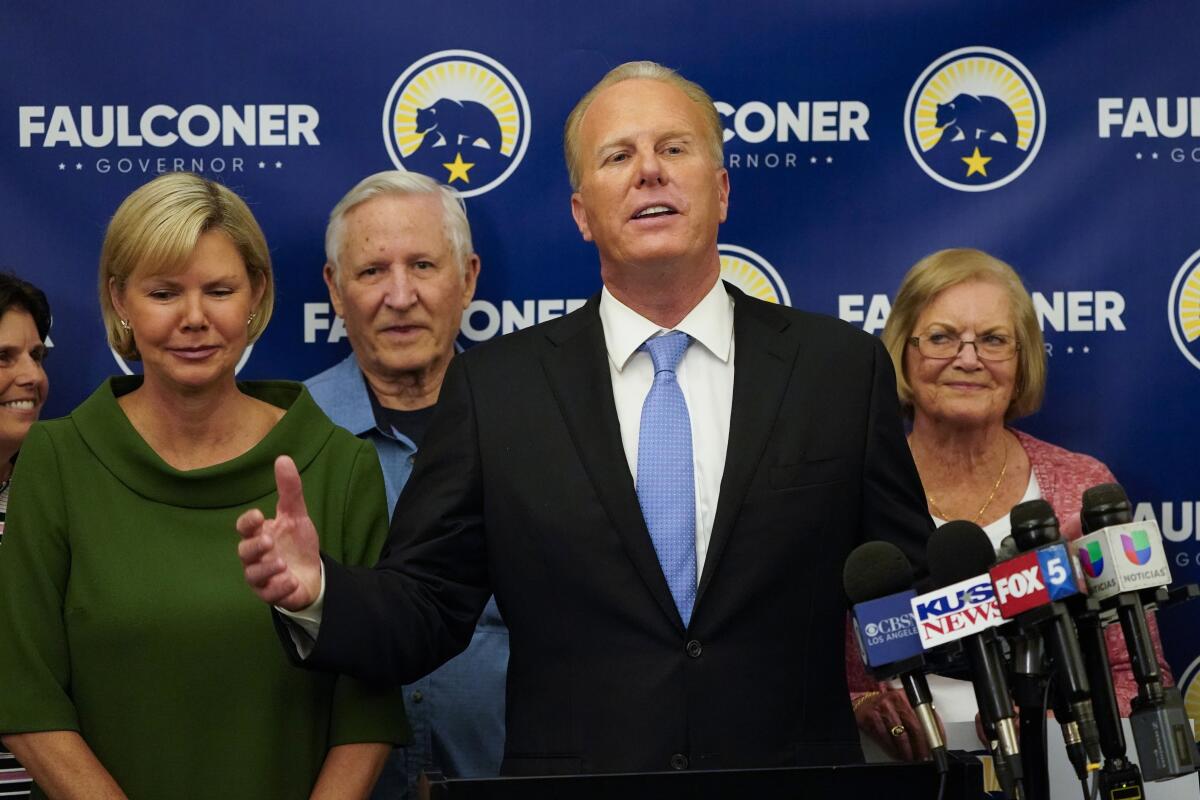

The state party failed to coalesce around a candidate to replace Newsom or muster the money to counter the governor’s sizable war chest. The candidate long seen by Republican leaders as a potential savior — Kevin Faulconer, the moderate former mayor of San Diego — failed to gain traction with voters. Larry Elder captivated the conservative base, but moderates and hard-liners alike worry about his ability to expand his support if he runs for governor next year.

Newsom won by stoking fears of the GOP to turn out his base, and by touting his handling of the pandemic. Would the strategy work outside California?

To veterans of the state’s GOP politics, the recall fallout fits into a broader pattern of dysfunction.

“In California, Republicans don’t fall in line,” said Bill Whalen, once a top aide to former Gov. Pete Wilson, tweaking a well-worn political cliche about the GOP’s supposed discipline. “Instead, they line up to fall all over one another.”

Jessica Millan Patterson, chairwoman of the state GOP, said there were some silver linings to the recall process — citing an increase in the number of volunteers and contacts with voters — but acknowledged the results were hardly ideal.

“In my career, I’ve learned a lot more from my losses than I have from my wins,” she said. “This is a great opportunity for us to build.”

The state party’s tug of war between the establishment and its grass roots predates Patterson’s tenure by decades. Their differences are in some ways a matter of varying shades of red; staunch conservatives tend to lean into the culture wars with fervent opposition to abortion, gun control and illegal immigration, while moderates downplay those social issues and emphasize business-friendly policies instead.

But the disputes go beyond matters of policy. There are also geographic rivalries — Republicans in northern, rural and inland areas are often at odds with those from the major cities — and a deep skepticism among the grass roots of the professional political class of consultants, lobbyists and many elected officials.

Although the state has become a deeper shade of blue, there are plenty of Californians whose politics are aligned with the reddest areas of the country, and their clout among the grass roots has grown as moderates leave the party.

“The registered Republicans that are left in California philosophically are right in there with Republicans in Texas or Republicans in Tennessee,” said Jon Fleischman, a longtime GOP activist and former executive director of the party.

Republicans are in agreement they are in need of a turnaround, but find little consensus on how to do it. Moderate Republicans say the party must broaden its appeal beyond its hard-right flank even if that means sacrificing ideological purity.

It’s too easy in California to force a costly and wasteful special election like Tuesday’s vote.

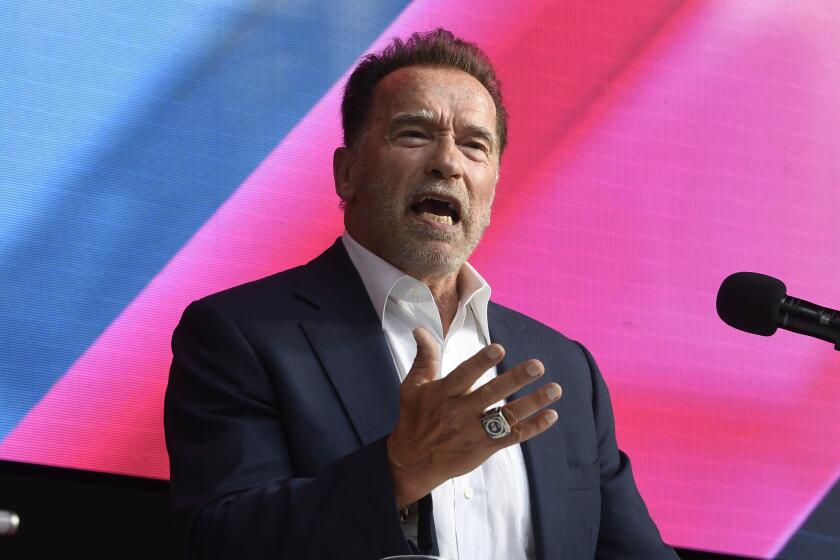

In 2007, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger famously warned his party that “in movie terms, we are dying at the box office.” On Wednesday, his assessment was even worse: “It’s now direct-to-video.”

Schwarzenegger was largely reviled by the Republican base by the time he left office for failing to hew to the party’s orthodoxies. But he said the GOP’s refusal to adapt its stances on climate change, healthcare, women’s issues and the pandemic is precisely why they lost the latest recall election.

He thought the party would have learned from its recent string of losses — “that they failed and they would understand why and make adjustments. But they haven’t,” he said. He accused his fellow Republicans of doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result: “It’s the definition of insanity.”

Aaron Park, a blogger who was a GOP party activist in California for two decades, said he’s used to hearing moderates blame conservatives like him for their losses. But he believes their preference for more centrist candidates is doomed to fail.

“You’re trying to run against a Democrat as a ‘Democrat Lite,’” Park said. “If people are given the choice between Budweiser and Bud Lite, people are going to drink Budweiser.”

Patterson, the party chair, said she did not see it as a choice between two opposing factions.

“I want to make room for everybody,” she said. “There’s too few of us in California to be at odds with one another.”

The recall effort was launched not by the California Republican Party apparatus, but by a band of activists who had unsuccessfully tried to trigger Newsom’s removal several times before.

Anne Hyde Dunsmore, campaign manager for the pro-recall group Rescue California, said the party “was not there for us in an active way” until just before the effort qualified for the ballot, when the GOP supplied a vital infusion of cash. Nor was the state GOP working in coordination with them once the campaign got underway, except in a few key congressional districts.

On Tuesday, the California voters most active leaned toward recalling Newsom, but that was just part of the overall picture.

The waning influence of party leaders was on full display last month, when the state GOP voted not to endorse any candidate in the recall race. In the past, party operatives had used the arcane endorsement process to elevate its preferred candidates and coalesce the Republican vote behind them.

The conservative grass roots has chafed at those maneuvers. When it came time to consider endorsing in the recall election, they resisted attempts to put the party’s backing behind Faulconer, whom they saw as a proxy for the establishment they despised.

Patterson, who initially supported the party making an endorsement, said on Wednesday the entire party delegation chose not to align with a candidate, keeping the focus instead on the question of recalling Newsom. (The two-step ballot asked voters first to weigh in on removing Newsom, and, separately, who should replace him.) But people familiar with the process said some in party leadership tried to steer the backing to Faulconer, only to reverse course when it was clear they would fail.

A party endorsement would probably not have been determinative in the recall election, which hinged more on the outcome of the first question of whether Newsom should be ousted than consensus on who should replace him. Still, the discord stood in stark contrast to the Democratic Party, which has been beset by its own power struggle between moderates and progressives, but united to prevent a major Democrat from hopping into the race to avoid muddling their anti-recall message.

Faulconer, in his concession speech Tuesday, made the case for the party to tack to the center, asserting that “California Republicans can’t look inward and appeal to ourselves. We have to build a big-tent coalition.”

But he acknowledged doubts about his ability to be the party’s standard-bearer in 2022.

“I’m going to take the time to talk with my family and supporters, and decide how best to serve the people of our state,” he said.

If he does make another attempt next year, his challenge is twofold: expanding his reach to those outside the GOP while winning over the party’s skeptical base.

“One of the services Faulconer has actually done for the GOP is accidentally unify the grass roots,” said Park, the blogger. “Faulconer has become the poster child for all the problems they all see” in the party.

While nearly half of voters opted not to choose a replacement candidate, Elder’s commanding first-place finish among those who did makes him the prohibitive favorite among Republicans in next year’s governor’s race.

“The candidates who finish very far behind Larry Elder will have a lot of explaining to do to the donor community on why they would be a viable candidate in 2022,” said Jim Brulte, a former state GOP chair and legislative leader.

As of Thursday evening, Faulconer was in third place, behind Elder and Kevin Paffrath, a Democrat and YouTube star.

Though Elder said his recall campaign cemented him as a powerful voice in the state GOP, on Thursday he cast doubt on running in 2022.

“It’s hard to see how the outcome would be any different unless I was able to raise at least as much money as Gavin Newsom has spent, but even then the thing is daunting,” Elder said to KTLA on Thursday.

Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger, who won office through a recall, says he’s glad Newsom wasn’t ousted

For moderates, Elder’s continued influence is more evidence the recall effort was ultimately an act of Republican self-sabotage.

“At the end of all of this, the governor is going to stay in office and be emboldened,” said Assemblyman Chad Mayes, a onetime GOP legislative leader who left the party and now represents Yucca Valley as an independent. Among Republicans, “the people who are successful are the conservative shock jocks, and [Faulconer] — the one guy who most reflected California’s values and could provide a message for the Republican Party to grow on — is going to be done.”

And there’s one other outcome Mayes sees from the recall attempt — a decisive decision in the perennial power struggle to shape the direction of the Republican Party.

“It’s the establishment versus the activists,” Mayes said, “and the activists have clearly won.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.