Column: How George McGovern and a campaign 50 years ago helped poison today’s politics

When it comes to figuring out how and why our political culture turned so ugly and awful there’s no shortage of explanations.

Income inequality and racial prejudice. A shrinking industrial base and declining middle class. Fox News. Social media. Bowling alone.

In a compelling new podcast, Ben Bradford makes the case for another factor. He cites a change in how we nominate our candidates for president, a reform, he says, that diminished the role of political professionals and encouraged appeals to the more ideological — which is to say polarizing — segments of the two major parties.

“You have different incentives as a candidate to what kind of voters you’re going to reach out to in a primary system than you would if you’re trying to get the approval of party leaders who want centrists,” said Bradford, a Los Angeles-based reporter and independent audio producer.

Put another way, he said, “Instead of drawing a big circle around the middle of the American electorate, candidates now have to draw a circle around just their own party’s voters.”

Unlike gerrymandered states, California may host as many as 10 competitive races

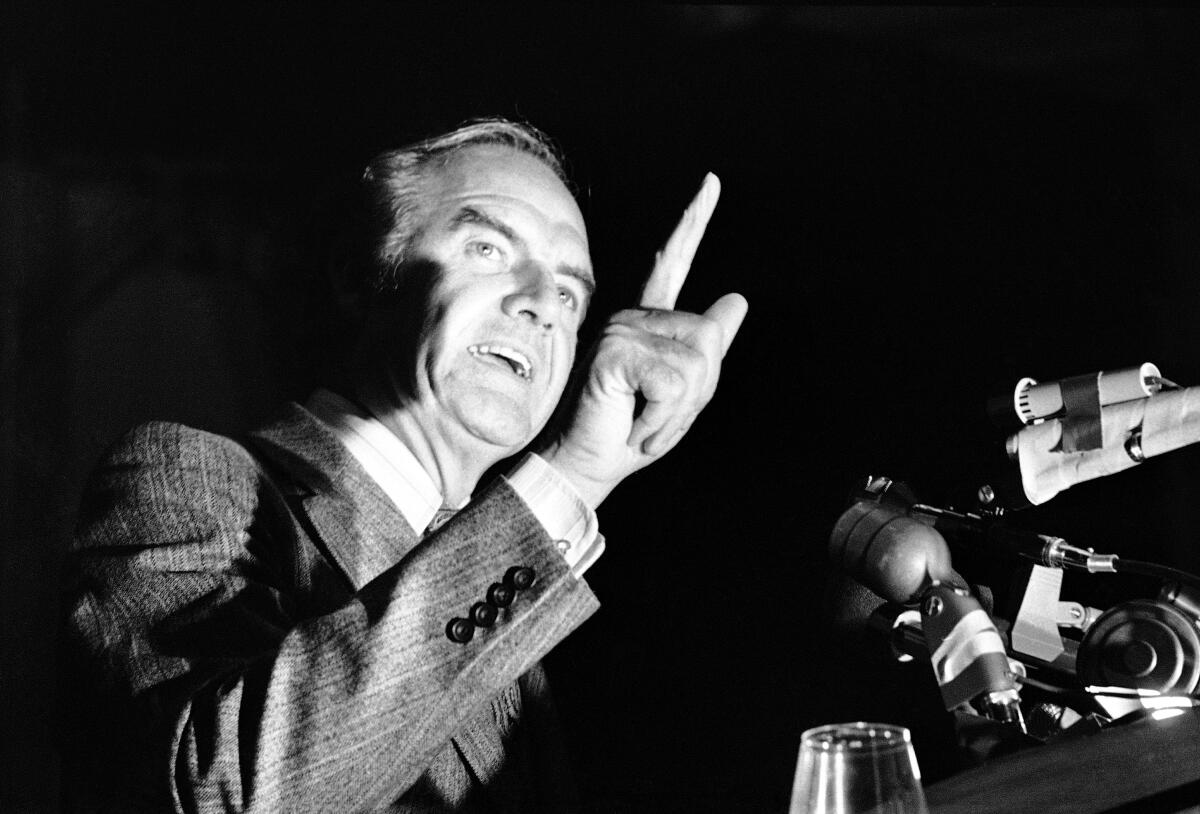

His focus is the 1972 campaign of the late South Dakota Sen. George McGovern. The story, told in seven episodes, begins in 1968 — one of the most tumultuous years in modern American history — and ends four years later with McGovern’s loss to President Nixon.

The changes to the nominating process came in response to the 1968 campaign and its upheavals, in particular the move by party leaders to anoint Democratic Vice President Hubert Humphrey despite fierce opposition from Vietnam War opponents. Owing to extraordinary circumstances — including the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy — Humphrey became the party’s nominee even though he didn’t compete in a single primary. A commission, led by McGovern, aimed to avoid a repeat of that scenario by boosting the power of women, young people and minorities and sought to ensure voters, not party insiders, chose Democrats’ next standard-bearer.

Republicans, for their part, ignored many of the proposed changes, but went along with expansion of the primary calendar — giving increased influence to the GOP rank and file — rather than allow Democrats to soak up all the attention with their nominating contests.

Benefiting from the delegate-selection rules he helped write, McGovern won his party’s nomination but proved a disaster in November; his defeat by Nixon was one of the most lopsided in history and henceforth the Democrat’s candidacy “became a cautionary tale,” as the podcast put it, “his name an insult for candidates who stray too far left.”

(The 1972 campaign, incidentally, was the last time California held a presidential primary that truly mattered. The winner-take-all contest came down to Humphrey and McGovern, who prevailed in a close finish. Political junkies will relish the archival recording of a fiery Assemblyman Willie Brown battling a last-minute maneuver at the Democratic National Convention to thwart the senator’s nomination.)

McGovern’s crushing defeat produced further changes to the nominating process — followed by changes on top of those changes — which over the last several decades have alternately increased and diminished the power of party leaders, or “superdelegates,” as Democrats call them. The through-line that Bradford sees is the marked decline of traditional power brokers in both parties, along with their ability to push candidates away from the margins and more toward the political middle.

“Candidates are incentivized to win a majority of voters in low-turnout elections,” he said. “In an environment where the parties have sorted ideologically, that means choosing polarizing, galvanizing issues — often cultural ‘wedge’ issues — that will turn out the most voters, often on a party’s wings.”

That doesn’t always translate to success. Joe Biden, for instance, won the Democratic nomination in 2020 even though he was among the more moderate candidates in a sprawling Democratic field.

It’s rather unappetizing to think the increased power of voters at the grass-roots level and the decline of party bosses have failed to make our politics vastly better. It’s hard to argue, though, that we haven’t simply traded one set of ills for another.

If it seems like Kamala Harris has vanished, it’s because she’s doing her job of not upstaging President Biden.

Bradford, 38, covered the 2016 campaign, among other assignments, for Capital Public Radio in Sacramento. Like many, he said, he was “taken aback at the level of division” the acrimonious election revealed in our country. He wondered what caused the deep chasm, and reverse-engineering led him back to 1972 and the resulting podcast, “Of The People.”

Speaking from his apartment and home studio in Koreatown, Bradford wasn’t terribly optimistic about the country’s political atmosphere improving anytime soon. He did say, though, he’d heard from listeners who came away from the podcast feeling some relief “just to hear how divided and tumultuous and violent this other period of time was 50 years ago, and how we came through that. So maybe there’s hope in that.”

These days you take solace where you can find it.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.