Does Pasadena’s Rose Parade disenfranchise voters?

For decades, each of Pasadena’s City Council districts has touched Colorado Boulevard — the route of the world-famous Rose Parade and the economic, entertainment and civic heart of the city.

But this tradition is leading redistricting experts and activists to claim that the seven districts are skewed in such a way that they may disenfranchise Latino voters and dilute the voices of downtown denizens.

For the record:

12:31 p.m. Dec. 12, 2021In this article, an earlier version of a map of the proposed Pasadena City Council districts mischaracterized the density of the Latino population. The map has been corrected.

Residents of the city’s core are split among multiple districts, leading to complaints that no member of the City Council truly represents their interests on issues such as development, transportation and pedestrian friendliness.

“If everyone’s in charge, no one’s in charge,” said Marsha Rood, the vice president of the Downtown Pasadena Neighborhood Assn., who wrote city officials a letter about her concerns last month. “Nobody’s pushing our issues. Nobody. They don’t go to bat for us.”

Redistricting experts say splitting this neighborhood may violate the state’s Fair Maps Act, which requires officials to try to draw districts that are geographically contiguous and avoid dividing neighborhoods or communities that share social or economic interests.

Others worry that the districts water down the voting power of Latinos.

At the request of The Times, GOP redistricting expert Matt Rexroad’s firm studied the proposed Pasadena map and census data. The firm found that although no current or proposed districts contain a majority of Latinos citizens of voting age, two could “easily” be drawn with such populations.

“This city is ripe for a legal challenge under the Voting Rights Act,” Rexroad said, referring to the landmark federal electoral law that prohibits racial discrimination in voting, including the dilution of minority voting power.

The city’s redistricting consultants say their maps are fair and have produced results: Pasadena’s elected leadership is diverse, with a Latino mayor and a council that includes three Black Americans, one Latina and one Japanese American.

Latino voters have the ability to elect candidates of their choice in three districts, said Douglas Johnson, president of the National Demographics Corp., and David Ely, owner of Compass Demographics. And they say that making major changes to the map would have ripple effects that would disrupt intermingled Black and Latino communities that have a history of cooperation.

“The maps perform,” Johnson said. “When districts are working and they’re achieving the purposes of the Voting Rights Act, we try not to blow them up.”

Intense jockeying underway as a state panel redraws California’s congressional seats

Like most elected government bodies, the Pasadena City Council is in the midst of redistricting, the once-every-decade redrawing of political lines that occurs after the U.S. Census Bureau releases new population counts.

Nationally, attention is laser-focused on the reconfiguring of congressional districts, which will influence control of the House after the 2022 elections. In California, redistricting is also being scrutinized as the state is losing a House seat for the first time in its history.

The U.S. Census Bureau released apportionment data, but the pandemic-induced lag has already caused ripple effects on redistricting and 2022 races.

Receiving less attention is the redrawing of district lines for city councils, county boards of supervisors, school district boards of education and other local government panels.

In Pasadena, the City Council is scheduled to vote on Monday on the proposed map.

The city’s consultants say each district touches Colorado Boulevard because of the thoroughfare’s historic importance as the center of commerce, government and recreation in the city — not because of the Rose Parade.

First held in 1890, the parade was created to show off the mild Southern California climate to Midwestern and East Coast residents suffering through cold, snowy winters. The parade along with the accompanying college football game are the premier events in Pasadena and a point of pride for its residents.

Johnson said he has referred to the parade route when talking about district boundaries, “but it’s a throwaway line to capture the much bigger picture.”

“Yeah, I would say that that’s something that sort of matters to council people a little bit, but it’s certainly not their highest concern, and it’s certainly not the reason that the districts are drawn that way,” he said.

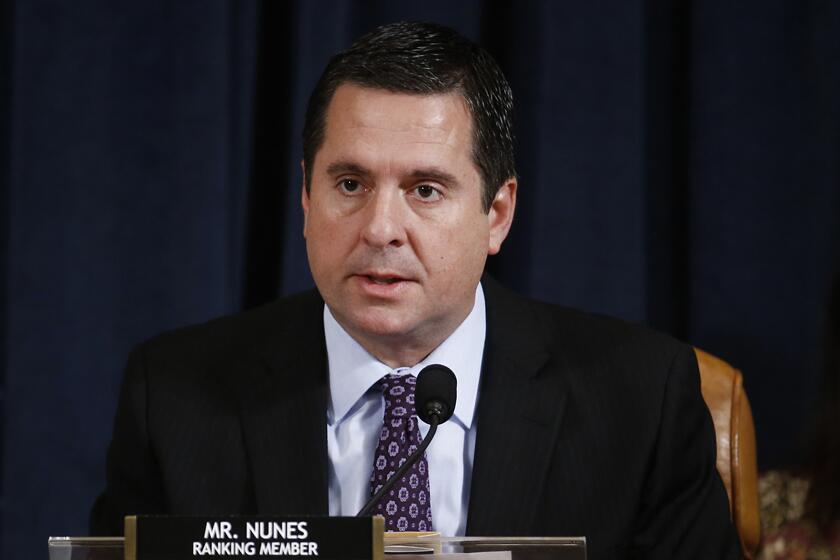

The controversial San Joaquin Valley congressman has served in the House since 2003.

Iterations of the proposed district lines have been in place for nearly three decades and have not been the subject of litigation. They were created as an effort to fix historic minority voter disenfranchisement in the northwest part of the city, said Ely, who has worked on Pasadena redistricting since the early 1990s. Previously, power in the city was concentrated south of Colorado Boulevard, and the 210 Freeway divided minority communities from the rest of the city.

In recent decades, the districts’ map “is a way of not maintaining the damage that the freeway did to those Northwestern communities — not isolating them from downtown Pasadena, from the business areas of Pasadena,” Ely said.

He also said that the proposed map includes three districts where Latinos have a significant say over who represents them. While none contain a population of more than 50% Latino voting-age citizens, they greatly outnumber other blocs of voters.

“The numbers are such that if the Latino community in any of those districts was unhappy with their representation and wanted to strongly challenge with a different candidate, they most certainly could win,” Ely said.

In a memo describing the proposed districts, members of the redistricting panel tasked with creating a map to present to the City Council also point to the electoral success of diverse candidates as proof that the rights of minority voters are not being harmed.

Three districts “have elected underrepresented minorities to Council quite successfully over about the last 20 years, thereby undercutting any argument that there is a racially discriminatory effect under the VRA in Pasadena,” the memo says.

As in many parts of Southern California, Black Americans’ moving patterns and the growth of Latino and Asian American populations have greatly changed the demographic makeup of Pasadena, a city of about 140,000.

In the first decade of this century, the Black population of Pasadena declined 24% to about 14,650 people. It’s now a little more than 12,500, according to the census.

Latinos make up about 46,000 of the city’s residents, of which 4 out of 5 are of voting age. Residents of Asian descent account for about 26,500 residents, with about 90% eligible to vote.

Other concerns downtown residents and redistricting experts have raised with city officials are not race-based.

It “takes a community of interest — residents concerned about traffic, noise, drunk people, crime — and splits them among multiple city council members, all of whom see their area as a fun entertainment piece,” said Paul Mitchell, a Democratic redistricting expert. “But none of them have to make the concerns of these residents their top concern.”

Rood, 77, agreed. The retiree started working for the city in 1982 and relocated there in 1988. She initially lived in a suburban swath of Pasadena until moving downtown in 2000. Her current way of life — walking to get groceries or to see a movie — is different than residents of the city’s less urban neighborhoods, she said.

“We are a community of interest that’s different than any other part of Pasadena,” Rood said.

Additionally, much of the development occurring in the city is taking place downtown. Developers with deep pockets contribute to multiple council members, while the residents do not have a single council member responsible for their concerns, Rood said.

Mitchell said this was a problematic structure.

Council members “get the benefit of donors but don’t get the negative of complaining residents who are impacted by the development,” he said. That results in a scenario “letting everyone have access to the trough but not having anyone who really cares about the people who have to live there.”

Ely said he and others who worked on the city’s redistricting proposal believe that consolidating downtown into one district would have been “highly disruptive,” potentially eliminating a district with a large minority population. He also said it could diminish the voice of downtown residents.

“If the policy choices of that district were different than the rest of the council, then you’d get one representative who is losing all the time,” he said.

Johnson added that it was imperative for all council members to have a vested interest in the city’s core.

“It’s the economic center. It’s also, of course, the government center, the cultural center of the city, all those things are all on Colorado,” he said. It’s “so that no district felt left out of essentially the heart of the city.”

José Del Río III, a redistricting advocate for the nonprofit government reform group California Common Cause, said the city’s rationale for having every district include part of Colorado Boulevard is irrelevant to the legal priorities that must be considered when drawing a new map, notably creating equal-size districts, not diluting minority voters and keeping similar communities together.

“‘Everybody has a piece of Colorado’ is not a criteria,” he said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.