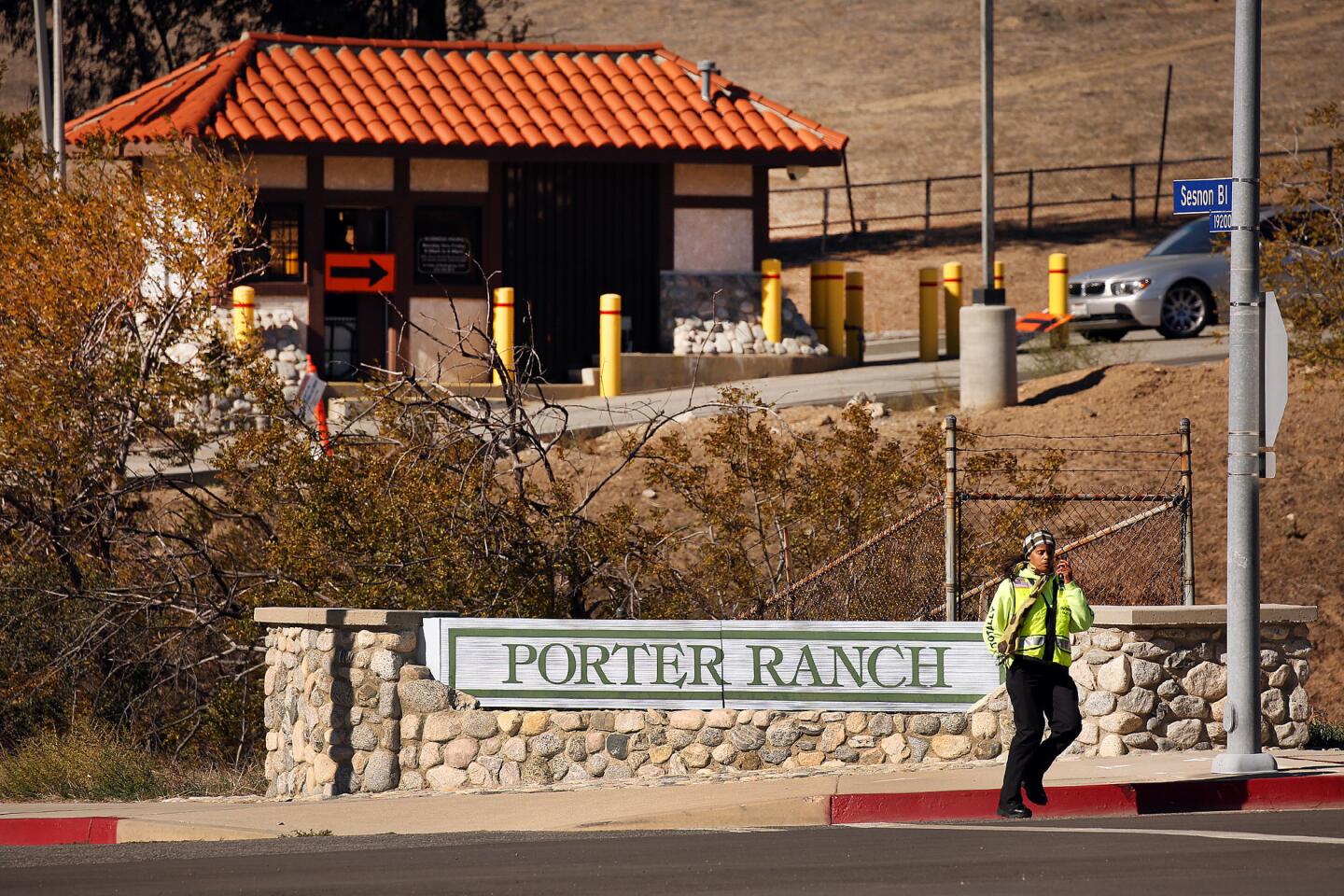

Porter Ranch leak declared largest methane leak in U.S. history

Scientists who flew an airplane equipped with sensors through the plume of natural gas leaking into the Porter Ranch area have found that at its peak, the nearly four-month leak released roughly 100,000 tons of methane — effectively doubling the methane emissions rate of the entire Los Angeles Basin.

The findings, published by the journal Science, cement the leak’s position as the largest methane leak in U.S. history — and highlight the need for rapid scientific response if and when such disasters do strike.

“Aliso Canyon will be, certainly, the biggest single source of the year,” said co-lead author Stephen Conley of UC Davis and Scientific Aviation. “It’s definitely a monster.”

The leak from a failed well at an underground natural gas storage facility in Aliso Canyon was detected by Southern California Gas Co. on Oct. 23. Since then, the invisible plume has filled homes in the Porter Ranch area with fumes, leading residents to report symptoms such as headaches and nausea. (The California Air Resources Board says it was not notified of the leak by the company until Nov. 5.)

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

Conley had been working with the California Energy Commission on a project to look for pipeline gas leaks in November when the agency asked him to head down to Los Angeles and study the gas pouring from the failed Aliso Canyon well.

“This was just a fortuitous event, that the California Energy Commission realized the importance of the Aliso Canyon situation,” the atmospheric scientist said.

Conley piloted a single-engine plane rigged with methane and ethane sensors through the plume and analyzed it during 13 different research flights between Nov. 7 and Feb. 13, with the last readings taken just two days after the well was temporarily halted. (The well was permanently sealed Feb. 18.)

With each flight, he would start very low — perhaps a couple hundred feet off the ground – fly through the plume, turn around and go back through at about 100 feet higher. He would do this until he reached the top of the plume, which could take anywhere from about 16 to 35 passes. Adding these slices up would give him the total emissions from the plume at that time.

Even after the first flight, the methane readings alarmed him.

“It was 20 times larger than anything else we’d ever measured — it was just kind of a shock,” said Conley, who recalled thinking, “What in the world was this big?”

Conley would typically send his measurements to the state Air Resources Board within two hours of leaving the site.

“They very much helped us understand the scope of what we were looking at, that this was far beyond any previous leak that we had dealt with,” Air Resources Board spokesman Dave Clegern said of the measurements.

Conley and colleagues also had help from UC Irvine atmospheric chemist and study coauthor Donald Blake, who used sampling canisters both on the ground and in flight to store some of the plume and take the contents back for analysis.

Flying through the plume was not fun, both Conley and Blake said. The odorants in the plume alone could induce nausea, but Conley had to make very sharp turns in part because of the narrow range of land they had permission to fly over.

Blake even became physically ill during one of the flights in the tiny plane’s cramped quarters.

“I’ve flown a million miles, and that’s not an exaggeration, with NASA and I’ve never gotten sick,” Blake said. “But Steve Conley made me sick.”

“Thank you, Steve,” he added, jokingly. “I took one for the team.”

The researchers were able to calculate that, over the 112-day event, the well released about 97,100 tons of methane, a greenhouse gas that is many times more potent than carbon dioxide, as well as 7,300 tons of ethane. Those amounts are equal to 24% of the methane and 56% of the ethane released in the entire Los Angeles Basin over a full year.

The leak is likely to hobble California’s attempts to meet the year’s greenhouse gas emission targets, they added.

“The radiative forcing from this amount of CH4, integrated over the next 100 years, is equal to that from the annual GHG emissions from 572,000 passenger cars in the U.S.,” the study authors wrote.

Thanks to Blake’s canisters, the researchers were also able to quantify the amount of benzene released in the plume. Though methane is not known to have serious long-term health effects, benzene is a known carcinogen. The levels came out to just a few parts per trillion for every part-per-million of methane — which, while elevated, were still very low in concentration, Blake said.

The results, which appear to be the first published since the well was plugged, are a piece of the puzzle that state officials say they have to put together to more fully understand the effects of the emissions from the Aliso Canyon leak.

“The flights that Steve Conley made provided good periodic measurements, snapshots of what was going on at a given moment,” Clegern said. “We need to figure out some very large gaps though, before we can really say what the overall impact is.”

The findings underscore the need for infrastructure that enables a rapid scientific response in these types of disasters, which are not uncommon in the U.S., the scientists said.

“It’s not the first time this has happened in the country,” said Conley, in reference to other natural gas leaks such as the dramatic Moss Bluff leak in Texas in 2004. The atmospheric scientist also lamented missing the first two weeks of the Aliso Canyon leak.

“I hope that one of the lessons learned is we need to have [some] sort of a rapid response methodology in place,” Conley said. “Somebody needs to be there in hours, not weeks.”

Follow me on Twitter @aminawrite and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS:

Five ways scientists are going after the Zika virus

Earliest known medieval Muslim graves are discovered in France

Scientists survey an Orange County neighborhood’s nonnative lizard populations