In a temple that predates the pyramids, scientists find evidence of a mysterious ‘skull cult’

More than 9,000 years ago, a mysterious group of hunter-gatherers built what might be described as the world’s first known temple.

Located in southern Turkey, this ancient place of ritual worship predates Stonehenge by 6,000 years and the first Egyptian pyramids by 5,000 years.

It is dominated by towering pieces of limestone up to 18 feet tall, carved into the shape of a T and adorned with detailed carvings of ferocious and predatory wild animals.

The site also contains an excessive number of fragments of human skulls — including some that now appear to have been carved by ancient human hands, according to a new study.

The ritual use of human skulls may seem macabre to most of us today, but the archaeological record suggests that skull cults — groups that assigned symbolic importance to skulls — were quite common in the area around the Mediterranean Sea at the time the temple, known today as Goebekli Tepe, was in use.

The site’s long-buried structures were built in the Stone Age — long before the invention of the wheel and pottery. Over the last 20 years, an international team of archaeologists has unearthed eight round buildings, each with two, large T-shaped pillars in the center and more T shapes embedded in the walls. There are also numerous statues, animal bones, carved beads, amulets and flint tools.

Researchers are still not sure what rites occurred in this haunting space — perhaps wedding ceremonies, conflict mediations or male initiation rites. (There is evidence that alcohol was brewed on the site, and the erect phallus is a recurring theme.)

Now, a study published Wednesday in Science Advances reveals that the people who came here to venerate their ancestors or their gods, or to mark life transitions, may also have been greeted by human skulls hanging from cords.

“It must have been quite an experience for them,” said Lee Clare, a professor at the German Archaeological Institute (known by its German acronym DAI) and coordinator of research and field work at Goebekli Tepe. “The buildings were semi-subterranean, and you can imagine the inside lit by a torch causing the T-shapes to flutter in the light. There was likely drumming and singing going on — and skulls, dangling.”

Archaeologists working in the region have uncovered “skull nests,” piles of skulls, that have been separated from the rest of their skeletons, as well as skulls that appear to have been decorated with ocher or covered in clay. Many of these skulls also feature scrape marks, suggesting they were dug up after burial and subsequently stripped of any remaining tissue.

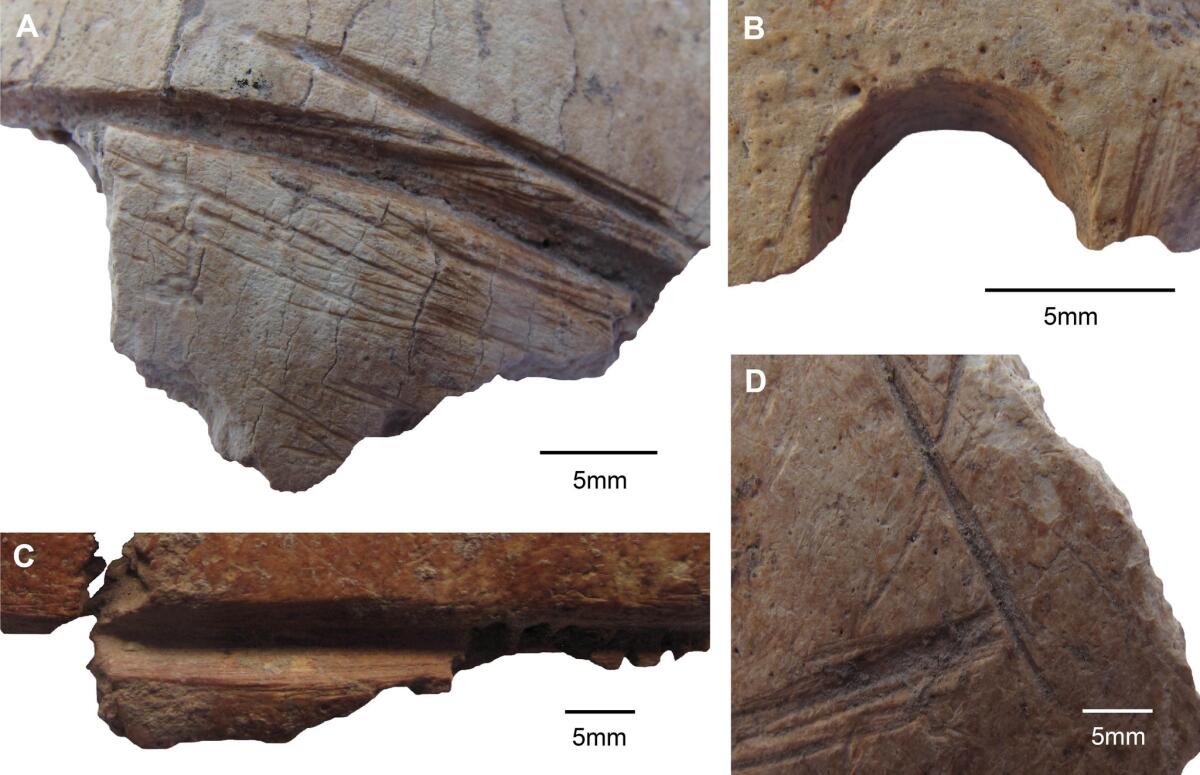

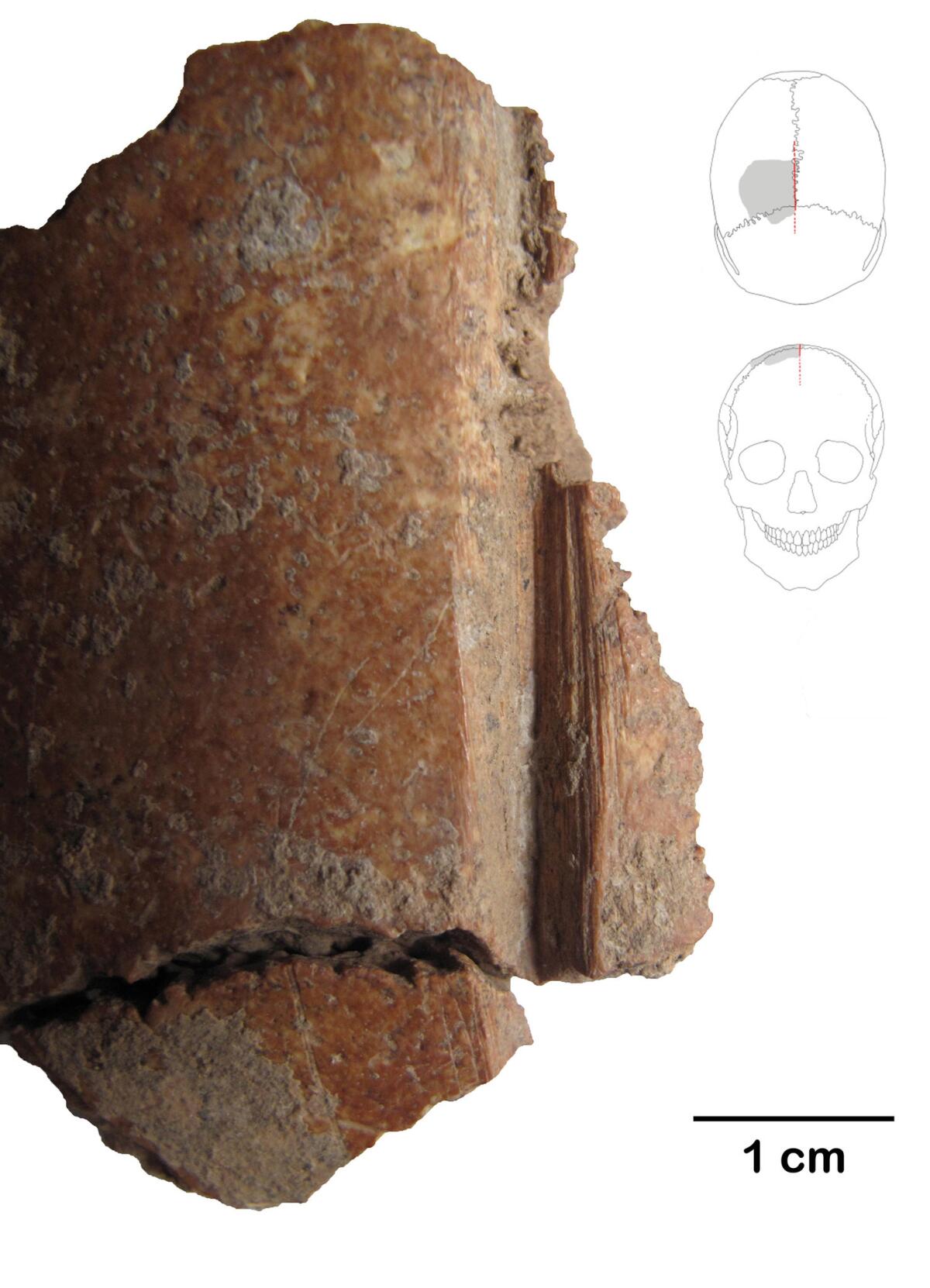

But at Goebekli Tepe, researchers found something they had never seen before: seven skull fragments belonging to three individuals with deep, straight, grooves carved into their surfaces. One of the fragments even had a hole drilled into its top.

“The skull cult in the Neolithic took on different forms and is frequently found, but the carvings are exceptional,” said Julia Gresky, an anthropologist and paleopathologist at the DAI in Berlin who led the work.

The grooves are between 0.2 of a millimeter and 4 millimeters deep, and microscopic analysis shows that they were clearly made using stone tools. The carved skull fragments also bear shallower markings that were probably made during the process of cleaning them.

There is no doubt that the cuts were made after death because there is no sign of healing on the bone, the authors wrote. However, it is likely that the carving occurred shortly after death. The bone was cut — and in one case, drilled — while it was still elastic, suggesting the modifications were made when the skull was still in an early state of decay.

Like most of the bone material discovered at Goebekli Tepe, the skulls were in fragments, so it’s difficult to glean much information about them. However, the study authors said, all three skulls belonged to adults between the ages of 20 and 50.

Still, mysteries abound. So far, 408 skull fragments have been uncovered at the site, but just a few show signs of this unique carving. Why? Did the carvings brand these particular skulls as important people in the community? Or did they once belong to vanquished enemies?

The authors also noted that the cuts do not appear to be decorative and therefore probably had a more utilitarian purpose. It is possible that the drill hole at the top of one of the skulls might have been used to suspend it with a cord. If that’s the case, the straight grooves might have been carved into the bone to help keep a string in place along the curved part of the skull.

“We interpret these grooves as a way to hold the skull together,” Clare said. “In a skeleton, the lower jaw tends to fall off. The grooves would have supported a string that could have been wound around the skull and kept it from slipping off.”

The carved skulls are not the only evidence that a skull cult probably existed at Goebekli Tepe, Gresky said.

Symbols at the site suggest that skulls played an important role in rites that took place at the temple. For example, a statue known as the Gift Bearer appears to hold a human skull in his hands, and a headless human is depicted on one of the T-shaped pillars. In addition, many limestone skulls or human heads have been discovered at the site.

The authors wrote that of 691 bone fragments found among the rubble at Goebekli Tepe, 408 are from skulls. This implies that human skulls were selectively present at the site.

More clarity about how the carved human skulls were used at Goebekli Tepe may come with time. The ancient temple compound is large and sprawling — roughly 22 acres. Although archaeologists have been working there for more than two decades, they have excavated less than 10% of the site, Clare said.

In the meantime, Gresky said she imagines these prehistoric people carving the skulls of their ancestors to mark them as special, or maybe to perform some act of commemoration. Perhaps the skulls were displayed in niches in the monumental stone circles, or hung from wooden rafters. Were they a comfort to those who visited the temple? Were they frightening?

“Unfortunately, we will never know exactly what happened,” she said.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

This cutting-edge bandage could make flu shots a thing of the past

How a fear of humans affects the lives of California's mountain lions

Scientists make water bottles the old-fashioned way to see if they were toxic to early Californians