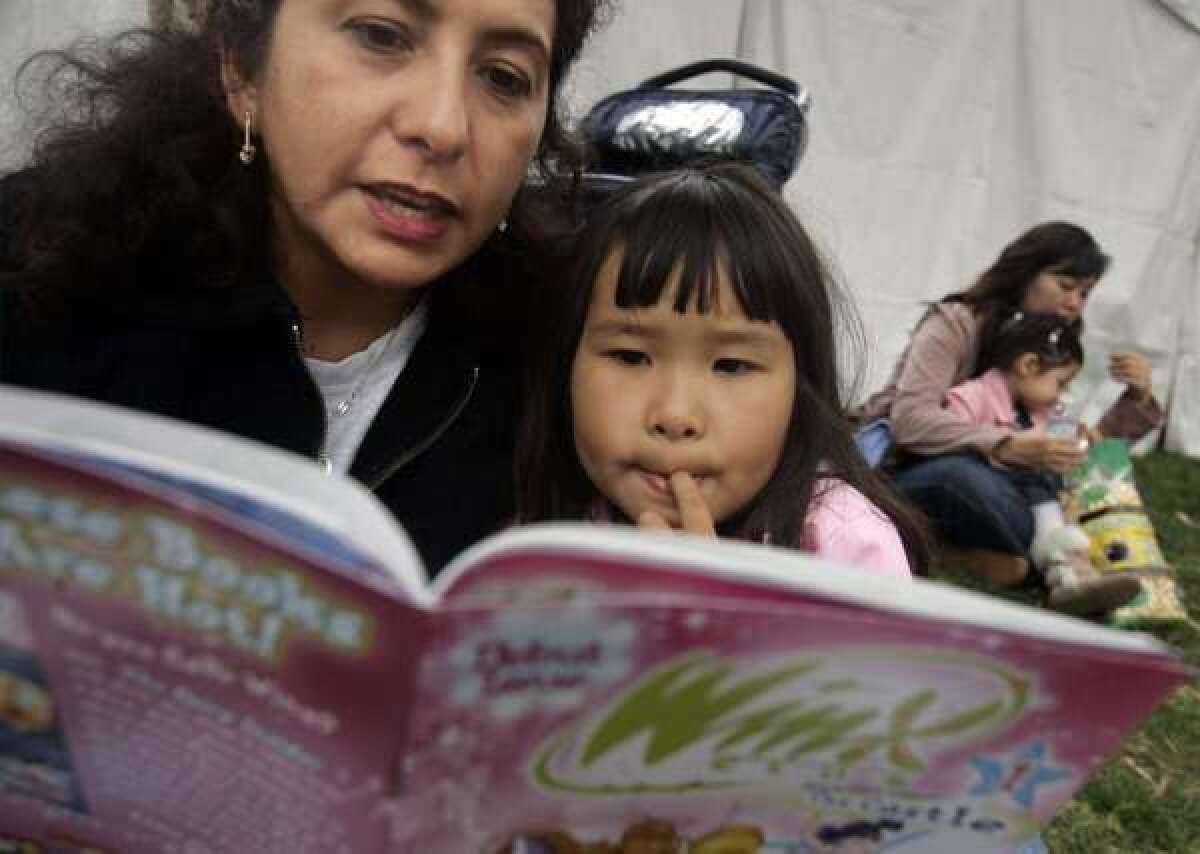

Want your kids to learn more words? Use your hands, study says

Before they set foot in kindergarten, some children are armed to the teeth with new words, while others come bearing far smaller verbal arsenals. What factors at home affect how wordy children’s brains are in their early years? A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says it depends not just on the words, but on how well parents use nonverbal cues.

Researchers have generally figured that the more that parents speak to their toddlers, the better off they are a few years down the line. Households with higher socioeconomic status – correlated with, as the study authors note, “more overt teaching styles and picture-book environments” – were thought to do better as well.

But scientists at the University of Chicago, University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University in Philadelphia thought there may be another factor at play: the quality of the speech, not just the quantity. Part of speech quality is nonverbal cues – whether you’re looking at, pointing at or interacting with what you’re talking about. For example, a child will be more likely to understand the word ‘giraffe’ if you’re pointing to a giraffe when you say it.

In any case, children don’t need a word to be repeated several times to pick it up, the researchers pointed out. Anyone who’s had a baby suddenly and sweetly blurt out a curse word at the dinner table – even when you’re sure the child couldn’t have heard it – knows that toddlers are remarkable little verbal sponges.

To test the idea, researchers videotaped 50 parents interacting with their toddlers during two 90-minute sessions recorded at ages 14 and 18 months. They had 218 adults watch 10 randomly selected 40-second clips from the recordings to try to guess the meaning of a bleeped-out word. Their success or failure helped scientists judge the quality of the recordings – whether the parents were effectively using gestures and other social cues to clue their kids in.

They found a range of quality in various parents’ speech, from 5% to 38%. What’s more, when they revisited the children around 4.5 years of age – just in time to start kindergarten – they found big differences between the kids whose parents had used better nonverbal cues when they spoke. Taken together, the quality and quantity of parents’ verbal input from three years earlier accounted for 22% of the difference between various children’s vocabularies at 4.5 years of age, the authors wrote.

Oddly enough, even though the amount of talking parents did to their kids varied with their socioeconomic status, their use of nonverbal cues did not – making quality of speech an “individual matter,” the researchers wrote.

The number words spoken might be important not because of the sheer total, but more because it raises the odds that a parent might use a nonverbal cue with an oft-repeated word. For example, if they say “nose” five times instead of once, there’ll be a higher likelihood that parents will touch their noses during at least one of those instances.

“The more words a child hears, the more likely it will be for that child to hear a particular word in a high-quality learning situation,” the authors wrote.