Coronavirus strains from California and the U.K. in battle for U.S. dominance

The grim horse race that is the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic has been reduced to a contest between two tenacious coronavirus strains: a variant native to California and an import from the United Kingdom.

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that the California strain accounted for 13% of all coronavirus samples that were genetically sequenced as part of a new federal program in late February. An additional 7% of the samples were the strain from the U.K.

Both versions of the virus have scientists and health officials on edge because they spread more readily than their predecessors and seem to be less vulnerable to some of the medicines used to treat COVID-19. The California strain has also shown signs of resistance to the current crop of COVID-19 vaccines.

Indeed, studies have found it to be 20% more transmissible than other variants in broad circulation. Its enhanced powers of transmission, ability to short-circuit the effectiveness of treatments, and ability to compromise the effects of vaccine prompted the CDC this week to declare the homegrown strain a “variant of concern.”

Known to scientists as B.1.427/B.1.429, it exploded in California throughout the fall and early winter as the state battled a deadly holiday surge. It now predominates in its home state and two of its neighbors. As of mid-February, it accounted for 52% of sequenced samples from California, 41% of samples from Nevada and 25% of samples from Arizona, CDC data show.

But the U.K. strain is giving it a run for its money — with a projected impact that ranges from uncertain to deeply worrisome.

In January, researchers at the CDC predicted that the U.K. variant would become the dominant one in the U.S. by March. Epidemiologist Summer Galloway, the lead author of that report, said Wednesday that it probably accounts for 20% to 30% of the samples being sequenced today.

The CDC does not have an equivalent estimate of how widespread the California variant is, Galloway said.

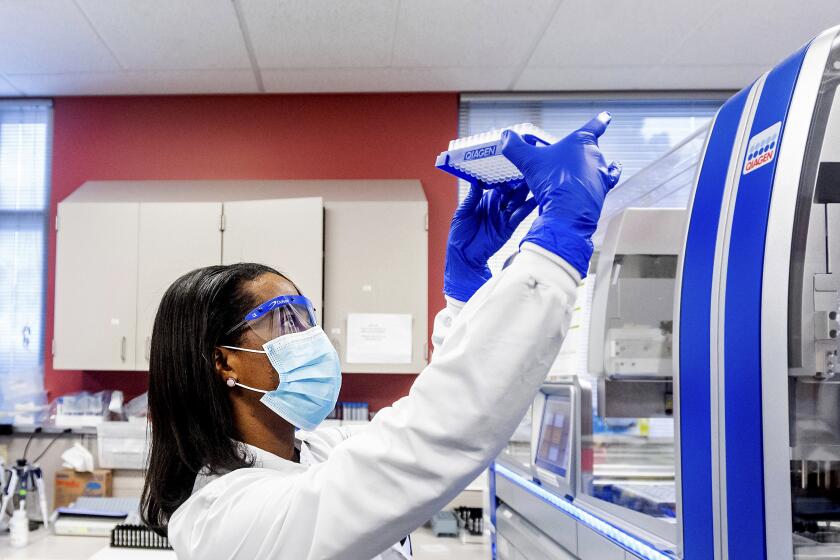

The Biden administration is boosting efforts to identify and track coronavirus variants to help scientists see where the pandemic is heading next.

What the genetic sequencing data do show is that the U.K. variant, known as B.1.1.7, is making inroads across the country and has fueled a handful of local outbreaks. Its documented presence has grown from 76 cases in 12 states in early January to 4,686 cases in all 50 states and the District of Columbia by late February.

The B.1.1.7 variant is thought to be as much as 50% more transmissible than other widely circulating variants, and a study published this week in the journal Nature suggests it is 61% more likely to cause severe disease or death.

The prospect that it could drive yet another wave of infections in the U.S. has helped drive a determined effort to expand vaccinations.

At the same time, however, many state governors are loosening restrictions on mask wearing, restaurant dining, and attendance at large gatherings.

The new CDC findings prompted Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, to declare that the California variant “is on its way to obsolescence.”

The fact that the U.K. variant’s transmission rate is higher than that of the California strain means the latter “will be quickly crowded out by B.1.1.7,” he said. In a contest for population dominance, “spreading rules the roost.”

British scientists have bolstered their case that the new coronavirus variant spreads more easily than its predecessors. It could be worse in the U.S., they warn.

Topol said two other variants — one identified in South Africa (called B.1.351) and another in Brazil (P.1) are likely to meet the same fate “because they do not carry such enhanced spread capacity as B.1.1.7.”

Galloway said neither the South African nor the Brazil variant has gained much of a foothold in the United States. While both are also designated “variants of concern,” neither has accounted for more than 0.05% of coronavirus infections genetically analyzed in the country since January.

But in Minnesota, Michigan and Florida, sudden flare-ups of new cases involving the U.K. variant have posed new challenges to public health officials struggling to bring the pandemic to a close with aggressive vaccination campaigns. Those outbreaks suggest that estimates of B.1.1.7’s greater transmissibility have not been exaggerated.

In Ionia, Mich., the variant was been at the heart of a major outbreak at Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility, where 1,600 prisoners are incarcerated.

On Feb. 9, state officials acknowledged an outbreak in which 80 prisoners appear to have been infected by a single employee. By Wednesday, even after the facility adopted an extensive program of testing, personal protective gear and limitations of movement, the number of infected people had risen to 425 prisoners and 26 employees, said Chris Gautz, spokesman for the Michigan Department of Corrections.

All of them were infected with the U.K. variant, Gautz said.

COVID-19 patients who take months to overcome their coronavirus infections despite treatment can become incubators of dangerous new strains.

In Minnesota, an outbreak involving the U.K. variant has halted virtually all youth sports in Carver County and put the state on tenterhooks as it reopens across a range of activities.

On Jan 9, the state noted five cases in its southwest corner. Just over two months later, the state has found more than 250 cases in more than two dozen counties across the state. Carver County recorded an overall weekly case growth of 80% from February to March.

In addition to being more contagious, the strain was also associated with higher mortality, “particularly among older adults and people with underlying conditions,” said Dr. Ruth Lynfield, the state epidemiologist and medical director at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Minnesota’s experience with the B.1.1.7 variant has also raised concerns about another of its attributes: its apparent ability to spread to and sicken children and young adults more readily than other strains. In Minnesota, fully one-third of the new cases were seen in people younger than 20.

This pattern has been documented by scientists elsewhere, but it has garnered less attention.

“What we’ve seen really does fit this picture of being very contagious,” Lynfield said. “We were seeing it among youth athletes and schools. And when we looked at teams, it really did have this high attack rate.”